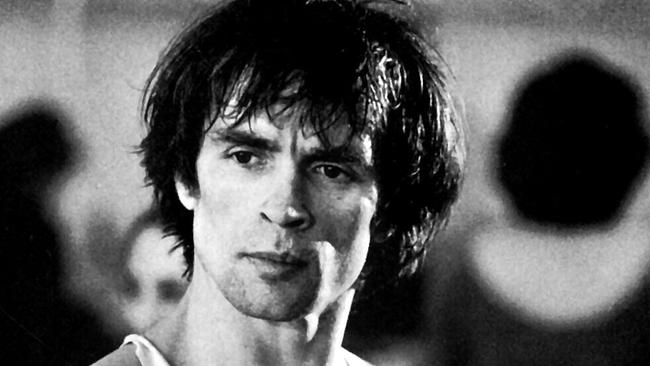

Nureyev defection: Clara Saint speaks for first time about her role

The woman who was the key to Rudolf Nureyev leaving the Soviet Union has spoken publicly for the first time.

More than half a century after the defection of Rudolf Nureyev, the woman who was the key to his leaving the former Soviet Union has spoken publicly for the first time.

The dancer fled into the arms of French police at Le Bourget airport in Paris, defeating efforts to stop him by Russian agents. He was helped by Clara Saint, whom he had befriended over the previous six weeks during the tour of the Kirov Ballet.

She sped to the airport on June 16, 1961, after a phone call telling her Nureyev was about to be sent to Moscow.

Once there, she told him to go over to the gendarmes, as his Russian minders could not force him back when they and Nureyev were on French soil. Her act secured his defection.

“I said to him, ‘You see these two men, French police, you have to go to them,’ ” says Ms Saint in a program to be aired by the BBC. “It’s like in a ballet. He jumped. The French policemen took him, and then there was a fight between one of the policemen and one of the bodyguards.

“The French policeman said to the Russian: ‘Don’t touch me’, screaming ‘Vous etes en France ici.’ ”

Ms Saint was the 19-year-old daughter of a Chilean artist living in Paris and was engaged to the son of the French novelist and culture minister Andre Malraux. She met Nureyev, then the 23-year-old rising star of the Kirov. Their relationship was almost certainly not sexual, though Nureyev was still unsure of his homosexuality and had had liaisons with women.

Ms Saint, now 74, agreed to record an audio interview with Richard Curson Smith, the director of Dance to Freedom, but does not appear on screen in the documentary. “She is a very, very private person,” he said.

It was the death of her fiance, Vincent, and his brother in a car crash in May 1961 that deepened her involvement with Nureyev.

“It was my car,” says Ms Saint, who was informed of her fiance’s death while sitting in a box reserved for Soviets at a ballet in Paris as the guest of Nureyev.

“The two died in a car accident in the south of France. I did not want to look at all the magazines and newspapers. For me it was very important continuer sans plus penser” — to carry on regardless.

French dance critic Rene Servin says in the program: “Clara Saint was more in love with Nureyev than with her fiance.”

Curson Smith does not ask Ms Saint to confirm this, but suspects she was in love. Instead, he asks if Nureyev loved her. “I don’t think so,” she replies. “He thought I was an interesting person. I was free and I didn’t work at the time. Everything was easy with me. But, you know, he was such a star. I was happy for him.”

On their last evening before his defection, Ms Saint — who later worked for Yves St Laurent and Andy Warhol — assured him she would see him in London, where the Kirov was due next. In fact, the KGB had decided he would be hastened back to Moscow and had a plane arranged.

The KGB in Paris had become wary of Ms Saint’s close association with Nureyev, even sending reports to Moscow that she was a CIA agent. In the program, Ms Saint jokes about this accusation. “I was a paid CIA agent. Yes, I was Mata Hari.”

Nureyev’s love for the West was alarming for Soviets at the height of the Cold War. One interviewee suggests Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev had considered ordering Nureyev’s legs be broken to stop his career in the West.

Nureyev’s friends from the Kirov did suffer. “I was branded a traitor after the defection,” says one, Alla Osipenko. She was not allowed to travel abroad with the ballet company for a decade.

The KGB got Nureyev’s parents to write letters urging him not to betray his country. “It was particularly awkward for Nureyev’s father as he was a party official,” said Curson Smith. Nureyev was not allowed to return until 1987, five years before his death.

The defection was a propaganda coup for the West.

Michael Cox, professor of international relations at the London School of Economics, said: “It meant the West could claim a victory in the Cold War.”

The Sunday Times