Xi’s manoeuvres pushing Panama into tricky waters

Trump’s claim that Beijing is ‘operating’ the waterway are widely questioned but the country’s pro-US administration is caught in a new tussle for control.

When Bob Barnett booked his winter cruise from Los Angeles to Miami the plan was to relax and not worry about politics. He never imagined it would take him through a country his incoming president would threaten to invade.

“Never underestimate Trump’s ability to disrupt,” rued the Missourian, 68, as he took in the Panama Canal. Ahead, a vast oil tanker crept towards the first lock. The three tugboats nudging it into place were flying Panamanian flags.

Last month Trump declared that his administration would demand that the canal be returned to the United States “in full, quickly and without question”. On January 7, asked whether he would rule out using “military or economic coercion” to bring either the canal or Greenland under US control, his brusque response was: “No.”

His threat has been met with dismay by the pro-US government of Panama, whose president, Jose Raul Mulino, has since pledged that “every square metre of the canal belongs to Panama”.

The waterway was one of the great engineering achievements of the 20th century, shortening sailing times by weeks. The French abandoned an attempt to connect the Atlantic and the Pacific in 1889, with as many as 20,000 lives lost, mostly to disease. It was finally completed by the US in 1914.

The canal and the zone around it remained under American control until it was fully transferred to Panama in 1999 as part of an agreement signed in 1977 by Jimmy Carter. Trump has described that deal as “a big mistake”.

During the last quarter of a century the canal has been expanded, with wider locks that can serve the world’s biggest ships. It handles 6 per cent of the global maritime trade and brings Panama profits of $5.5 billion a year. Seventy per cent of the containers are travelling to or from the US.

Trump has two specific complaints: first, he claims that US companies and consumers are being “ripped off” and being charged disproportionately high fees to use it; second, he claims that it is “operated” by China.

Panama rejects both accusations, insisting that fees, which average $645,000 per crossing, are the same for all users. It concedes that prices have risen sharply over the past year because a drought has restricted the number of transits per day and led to a bidding war between shipping companies. It says that the US is the only country that is offered a significant discount - its navy gets reduced rates and priority passage as part of the handover deal.

Trump’s claim that China has taken over the canal stealthily is widely questioned. “You don’t control a canal from a port,” said John Feeley, former US ambassador to Panama. “There is a very solid intelligence and maritime security relationship that has built up between the United States and Panama over many years. And we are vigilant.”

Some still wonder whether the US is vigilant enough. In November President Xi inaugurated a deepwater port in Peru, part of a $2.1 billion investment. General Laura Richardson, former chief of the US Southern Command, warned at the time that the port might one day be used by the Chinese navy.

“China has global objectives, and we are clearly part of those global objectives,” said Euclides Tapia, professor at the University of Panama’s school of international relations. “In recent decades the United States has treated Latin America as if it is almost irrelevant. China has taken advantage of that situation and has been sneaking in.”

In 2017 Panama cut ties with Taiwan in favour of relations with China.

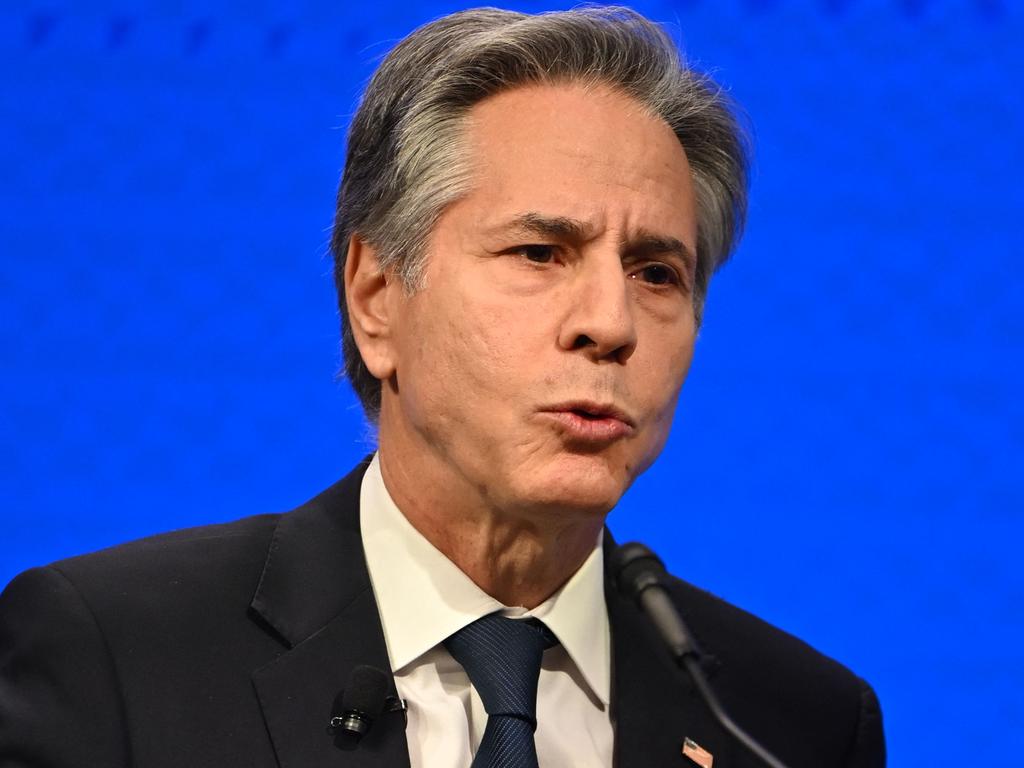

In his approval hearing at the Senate last week, Marco Rubio, the nominee for secretary of state, described China’s growing global influence as “the defining challenge of the 21st century”.

Of the five ports on the Panama Canal, two are run by a subsidiary of the Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison Holdings. One is on the Caribbean side, the other on the Pacific. China will have a window into what passes through this important thoroughfare.

At the Caribbean end, the port of Colon was once a booming trade hub and playground for Americans. It has fallen on hard times and unemployment is at historic highs. Most of its art deco buildings have succumbed to the salt-laden air.

All the Panamanians the Times spoke to in Colon were nostalgic about the pre-1999 days when the canal was run by the US, there was an American military base on their doorstep and jobs were plentiful. Many seemed to think it was a realistic possibility that the “gringos” would be back and that Trump was serious when he said the canal would be reverting to US control.

“I’m ready to fight for him,” said Ricardo Brown Bravo, 68. If Trump’s main aim is to disrupt, he has already succeeded in Panama.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout