Xi’s China may one day lead the world. But it won’t be loved

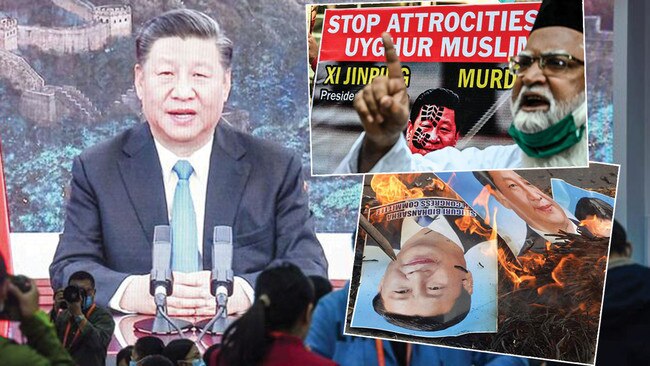

China has built the economic and military clout a superpower desires. The cost is a world learning to distrust — even hate — Beijing.

President Xi of China has everything that the leader of a nascent superpower could desire. His economy remains on course to overtake America’s as the largest in the world. His armed forces are acquiring submarines, high-tech missiles and aircraft carriers as the country transforms itself from a territorial to a regional to an international power. Mr Xi is respected; in many ways he is feared.

No love

But one thing is lacking: he, and his country, are not loved. In fact, according to the Pew Research Centre, a nonpartisan think tank based in Washington, China is actively distrusted, disliked or hated by more people than ever before. It found in a recent survey that in the countries of the industrialised world more people hold a “negative opinion” about China than at almost any time in the past decade.

In Japan 86 per cent fell into this category, in the US it was 73 per cent and in Britain 74 per cent; up 19 points since last year and 60 points since 2006.

This dislike is personal. Asked about Mr Xi as an individual, three quarters are sceptical of his qualities as a leader, and half have no confidence in him at all.

None of this makes much difference to Mr Xi’s status at home, where he governs as an unelected autocrat answerable only to the Chinese Communist Party. But strategically it matters profoundly to a government that has expended effort and expense in an unsuccessful effort to win international friends and admirers.

History suggests that apart from economic wealth and military might, an enduring superpower needs some form of love for its ideals, its artistic products and its popular culture. For all the harm it did, the British Empire left behind systems of government, law and education that serve its former colonial subjects even today. The American dream of opportunity may have been compromised by inequality but it remains a seductive idea.

Pandas and a pandemic

Modern China has a few indisputable cultural assets for which it is adored internationally; its cuisine, for example, and its pandas. But in most spheres it lags behind not only its strategic rival, the United States, but also its near neighbours.

Forty years ago Japan was a nation still defined, in the minds of many people in Asia and the West, by memories of military cruelty in the Second World War. Today it is a cultural superpower, admired in the East and West for products as diverse as cars, food, clothes, films, architecture and novels.

Even more remarkable, in its way, is South Korea, once an obscure Asian battlefield but which now has not only world-leading manufacturers such as Hyundai and Samsung but also, in the form of K-Pop, some of the world’s most successful pop musicians. In all the years since Beijing emerged as a superpower-in-waiting, there has still not been a Chinese Sony Walkman or Uniqlo or BTS.

This is not for lack of effort. China is acutely aware of the importance of what is known as “soft power”; in the words of the political scientist Joseph Nye, “the ability to get what you want through persuasion or attraction in the forms of culture, values and policies.” But China’s efforts to influence have often backfired.

Take the Confucius Institutes, a network of more than 500 overseas cultural centres in 162 countries. On the face of it these are no more sinister than the British Council or the Institut Francais — government-sponsored venues for the study of Chinese cooking, calligraphy and language, and providers of funding for scholar and students.

But time and again Confucius Institutes have been accused of using their influence to favour supporters of the Beijing government and to discriminate against those who challenge or oppose it, particularly in academia.

The Trump administration designated them “foreign missions” that must report to the government, and they have also come under scrutiny in Australia and India. In France an exhibition in the city of Nantes about the Mongol emperor Genghis Khan was suspended after accusations of censorship back home: the Chinese government, which was supporting the exhibition, had insisted on the removal of certain words that emphasised Mongolia’s historic independence from China. That stance was in keeping with the assimilationist policy that provoked protests over the summer in the Chinese province of Inner Mongolia.

Coronavirus scrutiny and ‘wolf warriors’

Never has China’s image been under such scrutiny as in the year of the coronavirus. You don’t have to speak of the “China virus” or believe in unproved speculation that it leaked from a Wuhan bio-lab to have concerns about the way Beijing handled the pandemic at the beginning, and its refusal to acknowledge what is widely seen as an early cover-up.

Then there are the “wolf warriors”, the new generation of assertive diplomats who advocate for China internationally — among them Liu Xiaoming, the outspoken ambassador to London — who have vehemently rejected reproaches about Chinese responsibility for the coronavirus. The nadir of wolf diplomacy came last month when a diplomat from Taiwan, which China claims as its own territory, was sent to hospital with a head injury apparently inflicted by two Chinese officials who were attempting to burst into a reception in Fiji.

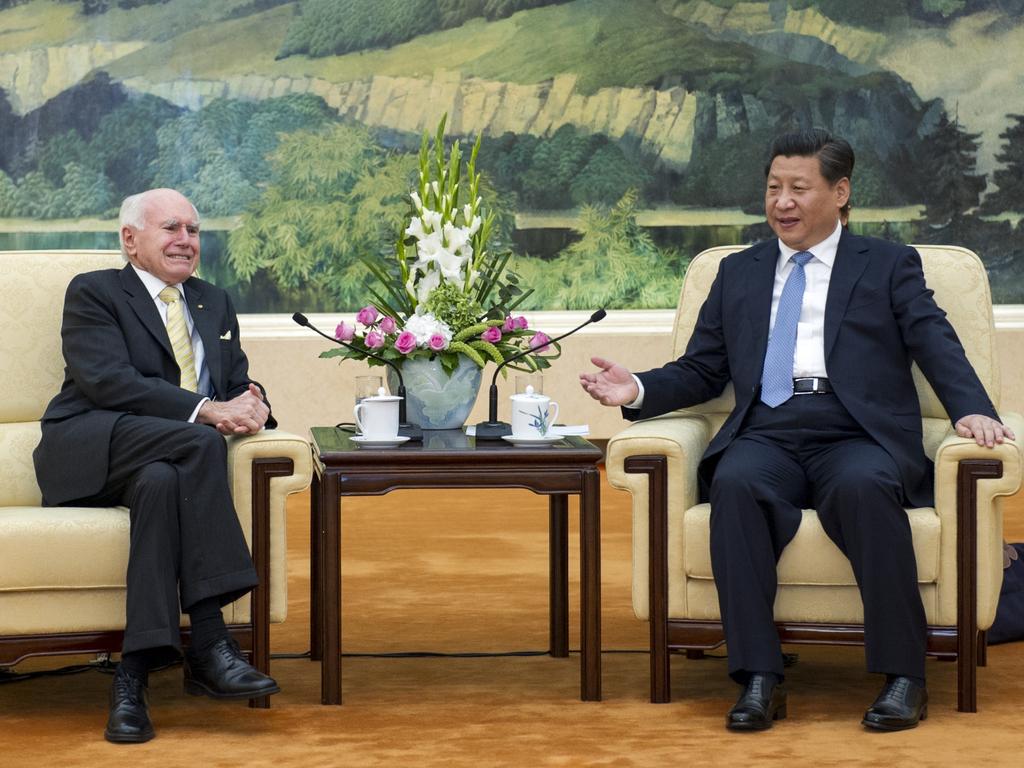

Kevin Rudd, a former Australian prime minister, and a fluent Chinese speaker, said: “Whatever China’s new generation of ‘wolf warrior’ diplomats may report back to Beijing, the reality is that China’s standing has taken a huge hit.

“The irony is that these wolf warriors are adding to this damage, not ameliorating it. Anti-Chinese reaction over the spread of the virus, often racially charged, has been seen in countries as disparate as India, Indonesia and Iran. Chinese soft power runs the risk of being shredded.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout