World waits to see if Trump’s trade moves were masterstroke or reckless bluff

US president’s China moves are either a masterstroke, or the bluff that reignited tariff war.

COMMENT

We’re about to find out whether trade wars really are easy to win. Donald Trump’s threat to hit a further $US250 billion of imports from China with a new 25 per cent tariff came just days before a Chinese delegation was due to arrive in Washington for three days of talks.

The markets had confidently believed that they would put the finishing touches on a deal to draw a line under the trade war that the US President started when he slapped hefty tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese imports last year.

Instead, Mr Trump’s dramatic escalation triggered a global stock market sell-off and led Beijing to scale back the trade mission to only two days.

By the end of this week we will know whether his brinkmanship was a masterstroke to end the war or a reckless bluff that reignited it.

That Mr Trump felt the need to escalate was evidence that the war was not going to plan. US officials have accused Beijing of backtracking on commitments that they believed had already been nailed down, including commitments by Beijing to change Chinese law to curb its subsidies to state-owned enterprises.

For their part, it’s possible the Chinese felt emboldened by recent signals coming out of the US.

In March, Mr Trump allowed a deadline for a deal to elapse without slapping the threatened new tariffs on China. In recent weeks, stories have appeared suggesting Mr Trump was prepared to water down his demands for new commitments on cybertheft. Beijing may have concluded that Mr Trump wanted a deal at any price.

Certainly, Mr Trump has reasons to be desperate for a deal. At a time when his diplomatic efforts in Venezuela and North Korea appear to be going nowhere, he urgently needs a foreign policy success.

He will also want to lift the dark cloud that persistent trade tensions have left hanging over the economy ahead of next year’s presidential election. Yet he must reckon, too, with hardening domestic attitudes towards China’s unfair trade practices. There is now a bipartisan consensus that Beijing must be forced to reduce subsidies, end forced technology transfers and cybertheft and remove protectionist tariffs and regulations that penalise foreign firms. Democrats may originally have attacked Mr Trump for launching his trade war with China, but the president is sure to be attacked if he agrees any deal that allows Beijing off the hook.

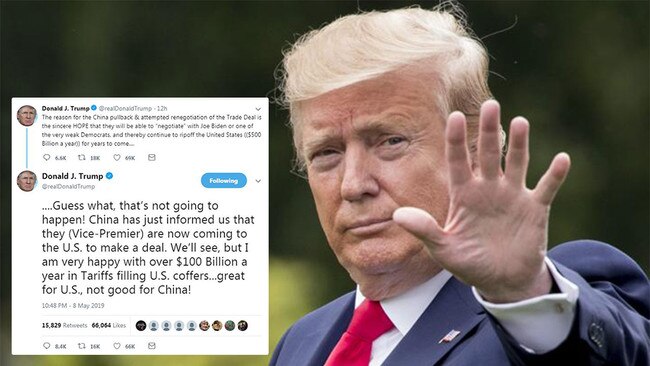

....Guess what, that’s not going to happen! China has just informed us that they (Vice-Premier) are now coming to the U.S. to make a deal. We’ll see, but I am very happy with over $100 Billion a year in Tariffs filling U.S. coffers...great for U.S., not good for China!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 8, 2019

But is Mr Trump really willing to see through his latest threat? He may feel emboldened by a recent upturn in the US economy, which suggests that the trade war has taken less of a toll on the economy than feared.

That said, his Twitter boast at the weekend that the costs of the trade war so far have been entirely borne by China is clearly untrue.

Although the US balance of trade narrowed in the first quarter, largely as a result of the Chinese decision to resume purchases of US soya beans ahead of the expected deal, the US trade deficit has widened since the first round of tariffs. An analysis by the San Francisco Fed reckoned that the impact of tariffs so far had been to push up US inflation by 0.1 percentage points, which is negligible. But if he was to implement the next round of threatened tariffs, consumer prices are expected to rise by 0.4 percentage points.

Betting on Beijing backdown

Mr Trump may be betting that the Beijing will nonetheless back down, since the costs to China of an escalation will be much greater. Beijing is already grappling with the consequences of a giant private debt overhang that it needs to unwind without strangling growth.

As things stand, Chinese growth this year looks likely to be somewhere closer to 6 per cent than the government’s target of 6.5 per cent, its lowest in a decade. New US tariffs will further dampen growth by squeezing exports and piling higher costs on to Chinese firms to the extent that they are unable to pass tariffs on to US consumers. Chinese firms also would suffer if Beijing decided to counter the US with its own retaliatory tariffs.

Until now, China’s tariffs have been structured strategically to focus on politically exposed US sectors, such as agriculture. But any escalation would require Beijing to extend tariffs to industrial sectors that would hit domestic manufacturers that rely on imported intermediate goods.

Will Mr Trump’s escalation make it harder for Beijing to make concessions? The reality is that nothing about trade is ever easy. Trade deals may be win-win in aggregate, but the gains are never equally distributed between countries or sectors, while political attention often focuses on the losers. Governments must trade off protection for one industry and greater market access for another. A US-China trade deal was always going to be harder than most, since almost all the concessions are expected to come from China while the immediate gains will accrue to the US.

What’s in it for China is the easing of current tariffs and the long-term gains that will come from the liberalisation of its economy. The danger is that Mr Trump’s brinkmanship will instead strengthen the hand of China’s own economic nationalists, who want to maintain the present state-led economy.

Of course, it is overwhelmingly in Britain’s interest that Mr Trump wins his trade war. The whole global economy stands to gain from any deal that leads China to curb its unfair trade practices and removes the shadow of further tariffs. That said, victory for Mr Trump would bring new challenges. It would have been better if Mr Trump had confronted China in a common front with allies including the European Union that strengthened the multilateral trading system. The danger is that, by pursuing a bilateral deal underpinned by its own dispute resolution mechanism that bypasses the World Trade Organisation, a win for Mr Trump will further weaken the rules-based system, thereby undermining the protection the system provides for weaker countries. That could prove ominous for whoever is the target the next time Mr Trump decides to start a trade war.

The Times