Winter Olympics: the tainted Games

From Covid concerns and suspicions of state surveillance to warnings to stay silent and fears for athletes’ safety, there’s a gloomy shadow over the Beijing Olympics.

When the former Olympic skier Noah Hoffman was asked recently about his hopes for athletes competing at the Beijing Winter Olympics, standard wishes for sporting success seemed far from his mind.

“My advice to athletes who are there, and my hope, is that they stay silent,” he said during a webinar hosted by Human Rights Watch. “I fear for my teammates who are going to China. I’m scared for their safety.”

Such extraordinary statements have become the norm in the build-up to these Games, which begin on Wednesday in the Chinese capital. The once-mind-boggling fact that these will be the first Winter Games to depend almost entirely on artificial snow has become the least strange thing about them.

Historic for the wrong reasons

“These Olympics in Beijing will be historic for all the wrong reasons,” Minky Worden, director of global initiatives at Human Rights Watch, says. Nations including the UK and the United States have committed to a diplomatic boycott, in protest against human-rights abuses, including the treatment of the Uighur minority.

Team GB has warned athletes against taking personal devices because of the risks of hacking and surveillance, and offered them temporary “burner” phones. The athletes are contending with a litany of concerns — from catching Covid and missing competition to state surveillance and the host government’s track record of “disappearing” those who speak out against it.

“Speaking with teams who are preparing, the discussion has primarily been on Covid, cybersecurity, and safety, and not focused on sport,” says Rob Koehler, director general of Global Athlete, an organisation that advocates for the rights of athletes. He cannot think of a time when competitors have had this many pressures on their shoulders. “These are challenging times for athletes and it’s wrong.”

Covid and warnings to keep quiet

Last week, Amnesty International called on the British Olympic Association (BOA) to protect Team GB athletes’ rights to freedom of speech and to support them if they wanted to speak out against the Chinese government. Andy Anson, chief executive of the BOA, has said that athletes will not be prevented from voicing their opinions but has suggested they seek advice before doing so. But Global Athlete’s stance has been different: this month, it released a statement saying it would “strongly advise athletes not to speak up about human rights issues while in China”.

The infamous rule 50 created by the IOC — although partially relaxed last year — does not welcome protest for political reasons on Games turf, while Chinese authorities have explicitly warned competing athletes that they could be subject to “certain punishment” if they were to speak or act in a way that was “against Chinese laws and regulations”. Global Athlete says this combination “places every athlete at risk”.

“It hurts to say that to athletes,” Koehler says. It is an uncharacteristic position for his organisation to take: it has spent the past two years lobbying the IOC to have rule 50 rescinded in order to better protect athletes’ rights to freedom of speech. But he and his colleagues feel that the risks in these circumstances are too great. “It’s unprecedented and it’s ridiculous that we’re telling them that,” he adds.

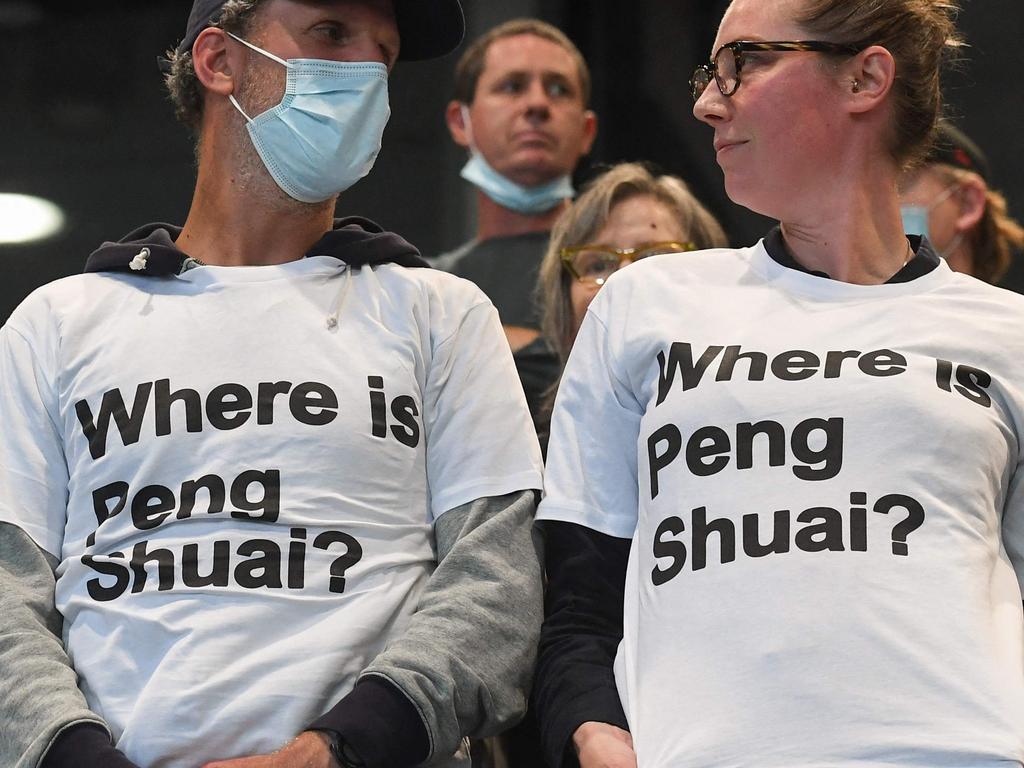

The Chinese government has recently given clues about how it views unhelpful public statements. In November, campaigners around the world demanded to know the whereabouts of the tennis player, Peng Shuai, after she disappeared from public view for weeks, following allegations that she made against the former vice premier, Zhang Gaoli, on social media. Posts about her allegations have been censored and removed online. The WTA has said that its tournaments will not take place on Chinese soil until they are reassured that the 36-year-old is safe and well.

The IOC’s strategy to diffuse the situation, which involved staging a video call between Peng and its president, Thomas Bach, was widely condemned. Last week, a handful of spectators at the Australian Open attended matches wearing T-shirts bearing the slogan “Where is Peng Shuai?”, sending the organisers scrambling. They later backtracked and said that the T-shirts would be permitted for the remainder of the tournament.

Foreign spectators banned

Chinese officials are unlikely to be concerned that these T-shirts will make an appearance at their Games, since foreign spectators are banned. While the summer Games held in Beijing in 2008 featured “protest parks”, where citizens could dissent in a controlled environment, no such concessions will be made — performatively or otherwise — this time. Critics have pointed out that, even if such a location were to exist, there would be very few dissenters left to populate it, after years of crackdowns by the government. China is no longer concerned with announcing itself on the world stage, as it was 14 years ago. It will, however, be keen to appear dominant and successful.

This is a more challenging prospect for its sports federations than the summer Games, in which the country routinely top the medals tables.

In the Winter Olympics, China have only once ranked in the top ten, in 2010, and won only one gold in Pyeongchang in 2018.

The country has shown characteristic determination to improve its standing in the lead-up to these Games, however, with the Ice and Snow Sports Development Programme. More than 3000 athletes have been in training for the national team before these Olympics, compared to about 300 before the previous Games. The president, Xi Jinping, has set a target of getting 300 million Chinese citizens into winter sports by 2025, aiming to create an industry around the slopes worth more than $AU192 billion.

Golden girl Gu

The former Canadian skeleton athlete Jeff Pain, who was hired to coach the Chinese team, told the BBC that his brief was to bring back a gold medal for the hosts, despite China having never fielded a single skeleton athlete at an Olympics before.

China’s most promising prospect in any event is Eileen Gu, or Gu Ailing (her Chinese name), an 18-year-old freestyle skier and contender for gold who has switched allegiance from the US to represent China.

Gu is the Chinese Emma Raducanu: highly intelligent, she has a place at Stanford University awaiting her after the Games, as well as deals with some big-name sponsors, and a host of modelling contracts with fashion brands.

Unsurprisingly, Gu has become the golden girl of the Games, the face of Beijing 2022, and, some argue, a valuable vessel for propaganda. Handily for the Chinese, she has remained tight-lipped on political issues, deftly swerving questions about her allegiances to the US and mostly talking about her hopes to be a role model for the millions of whom Xi Jinping hopes will now take up snow sports, particularly young girls.

Not all athletes may follow suit and stay silent, however. During the Human Rights Watch webinar, Craig Foster, a former Australian football player turned activist, directed a question to the president of the IOC. “Athletes have always felt compelled to speak out on broader social issues and rightly so. They may speak up. That’s a very serious matter,” he said. “If and when an Olympian speaks out on these issues, what is Thomas Bach going to do?”

We may get to find out over the next three weeks.

The Sunday Times

More Coverage

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout