Why coronavirus may turn into global epidemic

The difference between outbreak and epidemic comes down to one number. Have we already hit it?

The number of cases of novel Chinese coronavirus, we now know, may be ten times higher than initially thought. It is not the raw numbers that are worrying, though. It is that these latest estimates corroborate what Beijing has now admitted: the disease is spreading from person to person.

The difference between an outbreak and an epidemic comes down to one number, the most important number in disease modelling. That number is called R0, and it is known as the reproduction number – the number of cases created by each newly infected person.

If R0 is less than one, if it is even 0.9999, then a disease will die out.

More than one, and it will conquer the world.

When this new coronavirus was discovered, all those infected had been to the same animal market. Unlike with severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), which was a similar virus that in 2002 and 2003 killed 800 people in 37 countries, no healthcare staff appeared to have picked up a secondary infection.

This implied it only travelled from animals to humans – which in turn suggested an effective R0 of zero. The outbreak would die out.

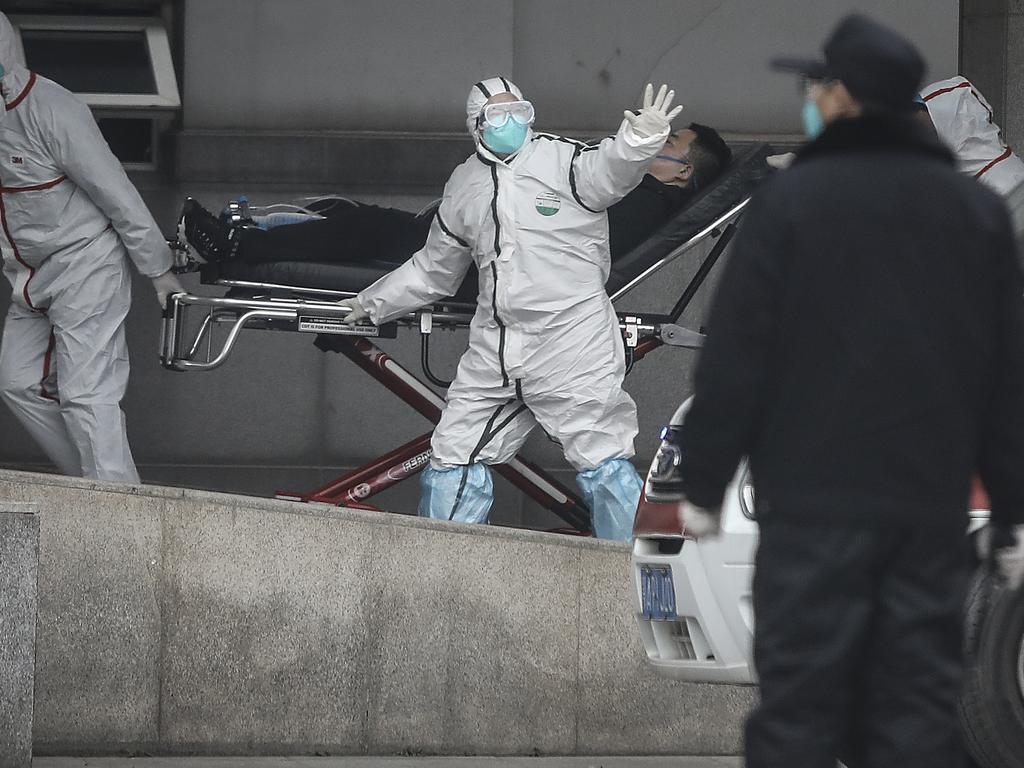

Over the weekend, global health chiefs have been forced to revise that assessment. There are more cases, in China and elsewhere. The first case in South Korea was reported on Monday, after other people in Japan and Thailand were diagnosed with coronavirus, which has already killed four people in China.

A Chinese government expert confirmed human to human transmission was already happening, telling state media that two people in Guangdong province had been infected with the virus after family members returned from the central city of Wuhan, the Ground Zero of the outbreak.

Zhong Nanshan, an expert in respiratory diseases, told reporters at least 15 medical workers had also tested positive for the virus, with one in a critical condition.

After modelling the travel in and out of Wuhan, where the virus originated, and then incorporating what we know about the disease, a team from Imperial College London believe that there may be 1,700 cases already.

Sir Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust, said we should expect many more. “Uncertainty and gaps remain, but it’s clear that there is some level of person-to-person transmission,” he said on Sunday. Like Sars, and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers) – both recent outbreaks based on variants of the coronavirus – one human can infect another.

There are, though, reasons to be positive. The first is the speed of response. Last week China released the genome of the new coronavirus to researchers, and unlike with Sars, there is little sense that authorities are playing down its spread.

The second is perhaps the most important: unlike Sars and Mers it does not, yet, appear to be too severe. Few people have died.

Indeed, that may be the reason that so many cases seem to have been missed.

“It is possible that the often mild symptoms from this coronavirus may be masking the true numbers of people who have been infected,” Dr Farrar said.

No one is, yet, complacent. Chinese New Year is coming, and with it one of the great annual shufflings of the world’s people. It is only after these millions have travelled to see their relatives and returned home that we will really come to an understanding of R0 – and with it the chance of those revellers taking a viral hitchhiker back with them.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout