That piece of ironic performance art was itself inspired by Joe Biden, who on a video call the previous day with Latino Democratic leaders called the Republican candidate’s supporters – that’s about half the country – “garbage”.

The President in turn was responding to a comedian at a Trump rally last weekend who described the American Caribbean territory of Puerto Rico as a “floating pile of garbage”.

And then there was this: ballot boxes containing early votes set alight by an arsonist in Oregon and Washington state, destroying hundreds of ballot papers.

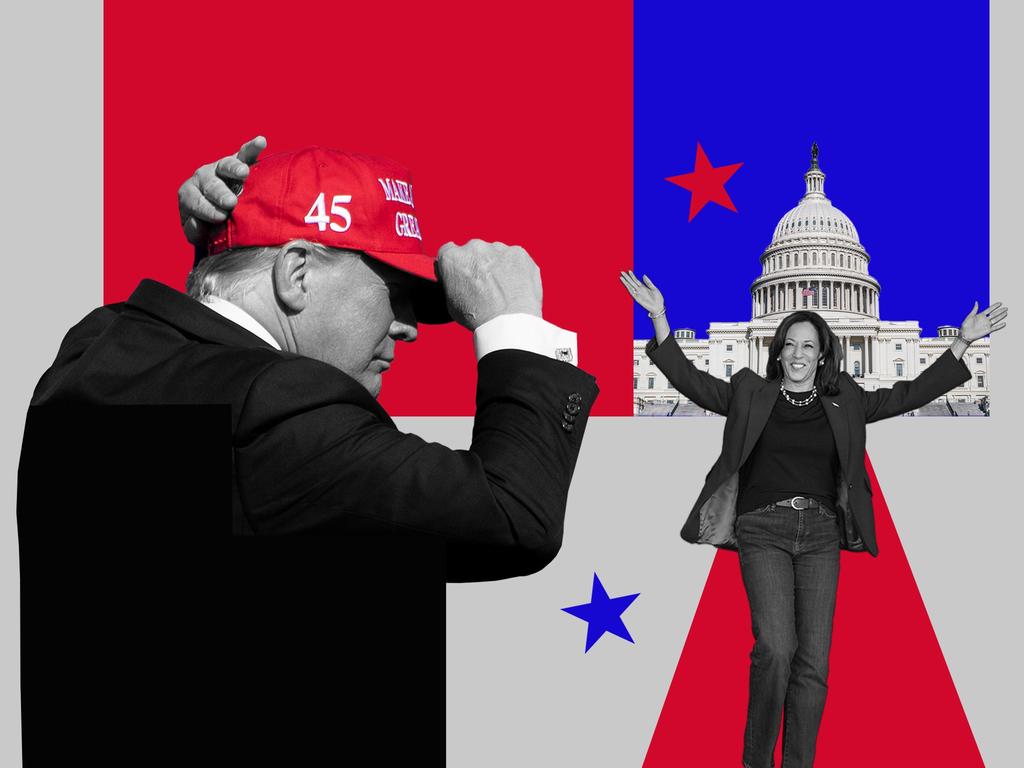

There you have it in toto, the imagery, rhetoric and flaming reality of a dumpster fire of a US election; a fitting funeral pyre for the detritus of a disordered and dispiriting campaign. It’s tempting to see also amid the garbage a metaphor for the state of modern America: heaped bits of singed debris of a once great democracy; the country that gave the world leaders like Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan now reduced to the antic dystopia of a system that elevates a pouting TV reality show host and dodgy real estate tycoon on the one hand, and on the other a tag-team duo comprised of an octogenarian party hack no longer in possession of what few marbles he once had and a babbling, giggling nonentity of a woman propelled to unearned prominence by a lifetime of male patronage.

But that’s too jaded a judgment. We are almost all victims of a tendency to see the worst in the present and the best in the past and, despite gauzy memories, not many presidential elections have really been exercises in Athenian-style democratic deliberation.

Still, there has been more than the usual cause for public despair about the quality of the 2024 race. Except for a few brief weeks in the summer when Kamala Harris replaced Biden as the Democratic nominee, none of these candidates has been viewed favourably by a majority of Americans.

Biden was too old and incapable and had presided over a record most Americans disapproved of, especially on inflation and immigration.

Trump was too malevolent, for many voters the memory of how he had left, or refused to leave, office in 2021 a cause for alarm.

Harris, once the “joy” her party tried to engineer around her candidacy faded, went back to being seen as just too empty.

This, perhaps as much as anything, explains the stalemate that has brought us to this point, days away from the election with the polls still indicating a dead heat and heavy, nervous uncertainty about the outcome.

With Harris and Trump as the nominees, much as it was when Biden was the Democratic candidate, the equilibrium between the two parties is as much the result of negative sentiment as it is of positive feelings. Each side cancels out the other – while each has a solid base of passionate support, each also benefits more than in the past from a fear and loathing of the other candidate.

This equilibrium remains the most important and remarkable feature of American politics and of this year’s campaign especially. In the face of a series of unprecedented events that might have been expected to shift the decisive weight one way or the other, almost nothing has really changed from a year ago.

Consider: in the space of a couple of months in late spring and summer, Trump was convicted of a felony, Biden suffered something close to a mental collapse in a debate with his rival, an assassination attempt came within millimetres of ending Trump’s life and the Democrats switched out the incumbent president, and replaced him, without a contest, with a candidate who had never won a single primary vote anywhere. Any one of those events in the past might have been expected to prove pivotal. We have had all four of them, each a political earthquake, and yet the needle hasn’t moved.

This stasis seems especially suspenseful because of what all deem to be the gravity of this election; a race so close seems to offer such a sharp divergence of options for the country. The two parties may be miles apart ideologically and in the character of their candidate but they both apparently agree on one thing: if the other side wins it will be the end of America.

This view has been most ardently articulated by Democrats and their many supporters in the media here in the US and around the world.

It goes like this: Donald Trump is a fascist, a man of demonstrated authoritarian instinct and intent who will, if he is re-elected, dismantle the constitutional architecture that has kept the US a democratic republic for nearly 250 years.

He has a well-observed enthusiasm for foreign autocrats and strongmen such as Vladimir Putin of Russia and Viktor Orban of Hungary. And last time around he actually showed that he was willing to resort to extra-constitutional means to try to stay in power even after losing an election.

Some don’t stop even at the “fascist” accusation; they claim that somehow he embodies just about every strain of totalitarianism of the 20th century.

“Trump is speaking like Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini,” Anne Applebaum, an American commentator who now lives mainly in Europe, wrote in The Atlantic last month. Since between them these three were responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of people and the incarceration of tens of millions more, this certainly suggests something of an upping of the ante of next week’s vote.

It is surely true that there is and always has been more than a hint of the autocrat in the language Trump uses.

His words often leave the unsettling sense that they may have sounded better in the original German. He told an audience in New Hampshire last year: “We pledge to you we will root out the communists, Marxists, fascists and the radical left thugs that lie like vermin within the confine of our country that lie and cheat and steal on elections.”

He has repeatedly denounced the “enemy from within”, another signature term of dictators and one wide enough, Trump has indicated, to embrace journalists and mainstream political opponents as well as radical activists. And in recent weeks he has spoken, with his customarily curious mix of menace and categorical vagueness, that he would be prepared to use the military on these “enemies”.

So does the fact that, with all this evidence of authoritarian intent on Trump’s part, he is still within a whisker of winning the presidency again, mean that half the American electorate – the “garbage” half – is ready to choose autocracy? Probably not.

Given the increased polarisation of the American electorate in the past 20 years it’s reasonable to assume that a sizeable portion of Republicans would vote for their candidate even if he were promising to turn America into Russia (and a similar number of Democrats would back their candidate if they were planning to make the US China).

But among the diminishing class of voters in the middle, support for Trump is not an endorsement of autocracy.

First, most of these voters discount the language and devalue the intent in Trump’s rhetoric. They remember Trump said 1000 things in his first successful run for election in 2016 that he never attempted to actualise in office – “locking up” Hillary Clinton most memorably.

They have got used to the hyperbole, and though many Trump voters I have spoken to around the country this year dislike the rhetoric, they take it less seriously than do his opponents. There are also doubts about whether even if Trump had the energy and inclination to be a totalitarian he could actually do it.

The US constitution is a thicket of checks on executive power, with balancing authorities in the judiciary and (even in a Republican-controlled) legislature, and a federalism that devolves powers to the states in ways that thwart the efforts of even the most ardent centraliser.

Second, their mistrust of what they are told by the main news media has reached the point where they simply disbelieve almost any reporting that portrays Trump as a menace to democracy.

A recent Gallup survey found that only 27 per cent of independent voters have a “great deal of trust” in the mass media, down from 50 per cent just 20 years ago, and 40 per cent when Trump first ran for office nine years ago.

Years of exposure to news organisations’ increasingly obvious bias against conservatives in general and Trump in particular have numbed them to any seriously negative reporting about the Republican candidate. A large majority of Republican voters, for example, and even a sizeable luminosity of independents, agree with Trump that the 2020 election was stolen, probably at least in part because the media tells them it wasn’t.

Having concluded that Trump is not a dictator in waiting, these voters have two main reasons for choosing him, despite whatever lingering reservations they still have about his character. First, he is in an unusually good position to benefit from widespread popular discontent with an incumbent administration.

All around the world this year incumbent governments have been falling, from the UK to Argentina to Japan. The causes are multiple and varied but broad popular dissatisfaction with inflation and the lingering aftermath of the handling of the Covid-19 pandemic have had repercussions for elected governments in Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America.

In the US, two thirds of voters tell pollsters they think the country is on the wrong track. Trump is especially well placed to take advantage of this because he was actually president in better times.

On the big issues about which voters express most dissatisfaction, the economy and inflation, Trump can point to his first term as a period of tranquillity that seems almost mystical by comparison. The benefit of hindsight is such that polls now say voters give him higher marks for his time in office than he ever got when he was actually president.

He doesn’t even get punished for a highly uneven response to the pandemic in his final nine months in office: Americans seem to succumb to a voluntary collective amnesia about that period.

But second, for voters planning to elect Trump, reservations they may continue to have about his character are more than offset by the still continuing appeal of the anti-establishment populism that first excited them about him.

The themes on which he was elected in 2016 have if anything been amplified by four years of the Biden-Harris administration. The alienation of working-class voters from increasingly distant and disdainful highly educated elites; growing despair about the condition of families and communities in the heartland, devastated by drugs and alcohol abuse; the sense that with mass immigration, the offshoring of jobs by rapacious capitalism and global economic trade deals US leaders of both parties have favoured foreign workers above Americans; anger at the sacrifice of young American lives in unwon wars – all of these continue to shape the politics of many voters.

In the past four years illegal immigration has exploded, inflation has undercut wage growth, the US has spent hundreds of billions on defence for foreign allies and the capture of the major cultural institutions by woke progressives who blame America’s woes on these least advantaged people has tightened.

Trump’s mastery of the iconography of populism – the ability of this billionaire domiciled in a vast estate in the most expensive zip code in Florida to portray himself as one of the dispossessed – is unmatched and undented. That rubbish truck stunt this week may have been a bathetic statement on the type of image-heavy campaign the candidates have waged but it captured better than any speech or TV commercial why so many regular Americans identify with him.

None of this guarantees a Trump win next week. The race remains on a knife edge and, if Harris is able to mobilise enough of her voters, she could win. But it does explain why, despite his manifold flaws, so many Americans think he is the better answer to the nation’s challenges.

The other great uncertainty about the election than the outcome is its aftermath. Next Tuesday may be just the beginning, whether one or other side is declared the winner, or, as seems likely, we enter a prolonged and tense standoff pending legal challenges and perhaps action on the streets.

This is a double-sided risk. While the media has focused on another eruption from Trump supporters if they lose, many Americans remember the summer of 2020 when left-wing activists rioted through dozens of American cities. The left is just as likely to have a collective nervous breakdown if Trump wins.

Does all this mean US democracy is teetering? America is a confounding country for observers. We have got used to the idea of it as a stable model of democracy in the past 50 years but it’s easy to forget that, despite its cultural similarities with Britain, unlike Britain it was born in revolution and its history has been shaped by the zealous interplay of revolutionary ideas. On one occasion that resulted in civil war. More often the strife has been fierce but was eventually resolved through democratic means - victory for one or other set of ideas and programs at the ballot box.

At the start of this year I wrote in these pages about how 2024 could look a lot like 1968, the climacteric of one of those periods of domestic strife. In the event the analogous events were mercifully tamer emulations of their forebears of 56 years ago.

This year, as then, a sitting Democratic president withdrew from the race, but this time he did so only after a terrible performance in a TV debate, not in the midst of a war that claimed the lives of tens of thousands of Americans. This year, a major party candidate was the target of an assassination attempt, but while Robert F Kennedy, like Martin Luther King before him, was killed, Trump lived. This year as then, the Democrats met for their convention in Chicago. But in 2024, unlike 1968, the party united immediately around its new candidate and the riot police stayed home.

One other parallel remains. But this one is unresolved. The election that year was also close. But in the political realignment it produced, and crushing defeat for the Democrats, it set the course for a historic break - away from the boiling international and domestic strife of the 1960s. Richard Nixon was eventually felled in a new crisis six years later but the political storms of the 1960s had been quelled.

The more consequential question next week may be not who wins but whether the country can move beyond it and finally start to dispel the dark clouds of its dangerous, volatile political equilibrium.

The Times

If you want a closing metaphor for the entire 2024 presidential election from this last week of campaigning, consider the scene in Wisconsin on Wednesday: Donald Trump donning a sanitation worker’s high-vis jacket, climbing into the cab of a rubbish truck emblazoned with the “Trump 2024” logo and being driven round and round an airport for the benefit of the television cameras.