When war is over, and Putin too, the problem of Russia will remain

The West is ignoring the lessons of history if it expects peace to reign when the Kremlin has a new leader

In November 1991, when the Soviet Union was on the verge of collapse, the British ambassador in Moscow, Rodric Braithwaite, received a warning from an adviser to Mikhail Gorbachev, the reforming leader who was about to be swept away, along with the country he had tried – and failed – to save.

“Russia may now be going through a bad time,” the adviser told Braithwaite. “But the reality is that in a decade or two, Russia will reassert itself as the dominant force in this huge geographical area.”

His words – repeated to me later by the ambassador – foreshadowed the increasingly assertive course of Vladimir Putin’s actions since he became president in 2000, culminating in the invasion of Ukraine in February.

Six months and tens of thousands of deaths later, Putin’s war grinds on. The stakes could hardly be higher. Fighting in recent days around the sprawling Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant prompted world leaders to warn of a nuclear catastrophe in the heart of Europe – akin to the meltdown in 1986 at Chernobyl,just over 600km to the northwest.

That accident both highlighted the failings of the Soviet system and precipitated its decline. A disaster at Zaporizhzhia would be the equally avoidable consequence of tensions that have boiled up in the region as a direct result of how the USSR collapsed.

The international community must somehow find a way to defuse these tensions. Yet the West appears to have given little thought to how it will co-exist with Moscow when, as seems likely, both sides eventually fight each other to a standstill. It would be wrong to believe we face a “Putin problem”. History suggests this is a “Russia problem” .

Opposite paths

The origins of the war lie in the unfinished business of 1991, when the Soviet Union broke up into its 15 constituent republics along often arbitrary internal borders transformed overnight into frontiers between sovereign states.

This rapid, largely peaceful transition under Boris Yeltsin merely postponed the violence that marked the slow-motion collapse of Yugoslavia, another multi-ethnic communist state: when the Chechens, whose homeland lay within Russia itself, tried to head for the exit, they were brutally crushed in two bloody wars. Putin’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 was ostensibly to protect the Ossetians, a pro-Russian minority, from what he claimed was “genocide” by the authorities in Tbilisi.

But it was the “loss” of Ukraine that particularly rankled with Putin, because of its size and shared origins with Russia more than a millennium ago. Control of the present-day nation’s territory fluctuated wildly from the Middle Ages until the Soviet period, but from the 1660s onwards much of it was ruled from Moscow or St Petersburg. After 1991 Ukraine was home to the largest share of the 25 million-strong Russian diaspora.

In the early years, Putin was not strong enough to do anything about the Russians of Ukraine. Nor did he have a pressing need to do so: although the country swung west after the Orange Revolution of 2004, it tilted back towards Moscow.

The Kremlin’s reaction to the Maidan uprising of 2014 – encouraged by the West – was very different. Putin seized Crimea and fomented an insurgency in the eastern Donbas, ostensibly in the name of its majority Russian speakers. By the beginning of this year it had already led to the death of more than 14,000 people.

Putin’s conviction, repeated on the eve of February’s invasion, that Ukraine had “never had its own authentic statehood” reflected not just his own view but that of many of his compatriots. About 64 per cent of Russians considered themselves and the Ukrainians to be “one people”, according to a poll that month.

Ukraine, by contrast, had rediscovered its rebellious past and developed a vibrant political culture shaped in large part by memories of wrongs perpetrated from Moscow. In the same February survey, just 28 per cent of Ukrainians saw themselves and Russians as one, though the figure rose to 45 per cent in the largely Russian-speaking east.

The target

The causes of Putin’s invasion this year – and how it could have been prevented – continue to divide those in the West who purport to know Russia best. The so-called “realists”, led by Henry Kissinger, blame the US for pinning the Kremlin leader in a corner by expanding NATO. The former US secretary of state would have preferred Ukraine to remain a neutral buffer between Russia and the West – “something like Finland” – although Helsinki has itself been persuaded by the conflict to give up decades of neutrality and join NATO.

Yet would the “Finlandisation” of Ukraine have prevented war? Or would Putin have found another pretext for grabbing a chunk from his neighbour of what he considers traditional Russian lands?

NATO had declared as long as ago as 2008 that Ukraine could join the alliance – much to Putin’s fury. More than a decade later, a timetable for Ukrainian membership had still not been agreed, nor did it look likely to be.

Ukraine was left with the worst of both worlds: it could be portrayed by the Kremlin as a NATO stooge, yet, despite growing flows of western arms, it did not enjoy the reassurance of mutual protection guaranteed to members under Article Five of NATO’s founding treaty. It was as if a target had been painted on its back.

Engaging with Russia

There has been little discussion of Western policy failings since Russia launched its invasion. Attention has instead focused on the progress of the conflict, as well as on the resistance of Ukrainian President Volodomyr Zelensky and his forces, coupled with the brutality of the invaders.

While Russia struggles to conquer the Donbas, a series of mysterious explosions in recent days in Crimea have opened a new front. The immediate aim is to disrupt the Kremlin’s war effort, part of which is conducted from the peninsula. Yet Ukraine appears to want to go further. “This Russian war ... began with Crimea and must end with Crimea – with its liberation,” declared Zelensky.

For Putin, the reconquest of the peninsula, which he has called Russia’s “holy land”, was a defining achievement. Losing it could pose an existential threat to his rule and encourage further escalation – perhaps, some fear, even the use of battlefield nuclear weapons – though Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu said last week there was “no need” for them.

Western leaders have largely kept silent on how to engage with Russia now and when the conflict finally ends. Policymakers in Washington and London appear inclined to hope Ukrainians will solve the problem for them by driving Russian forces from their country – followed by the departure from the Kremlin of a humiliated Putin.

This looks like wishful thinking, and not only because the more likely outcome remains stalemate. Putin is not obviously at threat either from disgruntled oligarchs or an unhappy populace. Sanctions are taking their toll on the Russian economy, but the full effects will be a long time coming.

Moving forward

The East-West tensions of the past few years are unlikely to disappear whenever – and however – Putin leaves power. Nikolai Patrushev, head of Russia’s security council, and other powerful figures in the Kremlin have ideas as hawkish as Putin’s own.

Russia will emerge weakened and isolated from its disastrous military adventure in Ukraine. But whoever succeeds Putin, the US and Europe will have to find a way of working constructively with the country whose course he has dictated over the past two decades. It cannot be allowed to remain an angry, brooding presence that casts a long shadow over the Eurasian continent.

Yet Russia itself must also change, just as Germany and Japan did after World War II, and western European countries did after accepting the loss of their colonies. Like former empires before it, Russia must shed its imperial mindset and accept that Ukraine and its other former lands have gone their separate ways. And it must learn to define its greatness in terms of its domestic achievements rather than at the expense of its neighbours. It is a big ask.

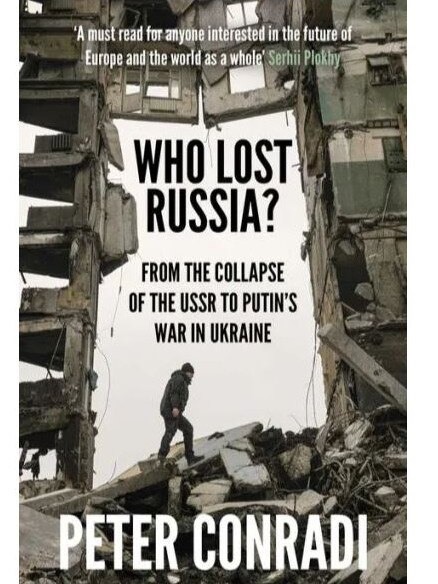

Who Lost Russia? From the Collapse of the USSR to Putin’s War on Ukraine, by Peter Conradi, will be published on Thursday

THE SUNDAY TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout