When AI kills jobs, expect a white-collar revolt

Humanity has weathered dramatic technological revolutions. But we have never done this before.

I’m already catching the first spooky rumours of the next industrial revolution. At lunch, a friend mentions a bank where the jobs of a whole team of PhD-level financial analysts are at risk after a new AI model outperformed them. An acquaintance in PR uses Chat-GPT to write emails to colleagues she suspects are doing the same thing – the humans are intermediaries in a robotic correspondence.

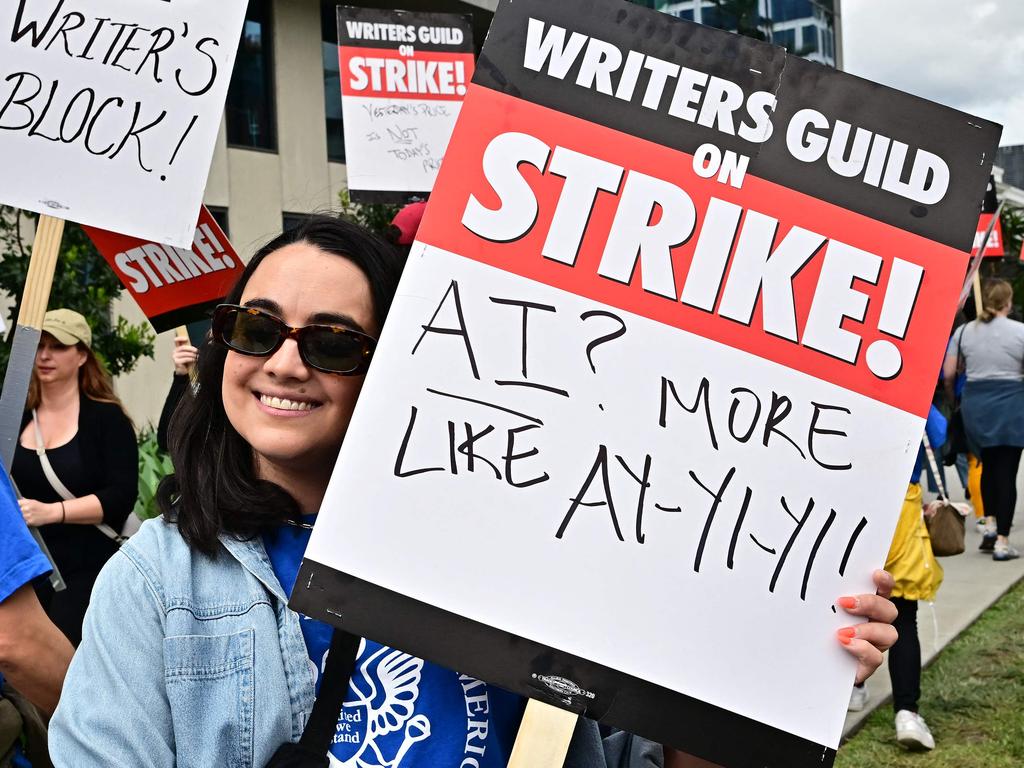

From a friend in publishing, I receive a flurry of anxious texts worrying not only that many editorial assistant jobs will soon be automated but that some authors will be too. Apparently, the less imaginative kind of romance novelist is thought to be at particularly imminent risk. If that sounds implausible, recall that screenwriters in Hollywood are striking in protest at studio threats to introduce TV scripts generated by AI.

Since the Newcomen engine whirred into life 300 years ago, humanity has weathered a succession of dramatic technological revolutions. But we have never done this before – that is, we have never used technology to eliminate jobs that provide not merely a livelihood but riches, social status and existential purpose.

I know lawyers and journalists (both of which are professions at risk of automation, according to a chilling document published by Sam Altman’s company OpenAI) who speak in basically religious terms of their “vocations”. Altman promised the US Congress on Tuesday that the jobs abolished by GPT-4 will be replaced by “much better” ones. Even if you believe him, it’s a dubious consolation. For many professionals there is no better job. I can’t think of one I’d rather do. Pressing the “generate column” button on Marriott-GPT every Wednesday morning doesn’t seem like it’s going to be as fulfilling.

The nearest analogy in recent history is the destruction of working-class jobs by globalisation in the early 2000s. Though a career spent on the assembly line at a Midwestern car plant is not the sort of thing you boast about at a smart cocktail party, industrial labour provided generations of blue-collar workers with an identity, a community and a source of pride.

The abolition of those jobs precipitated a cultural collapse – homelessness, social disintegration, the bleak advent of “deaths of despair”. This misery and resentment helped to propel the political career of Donald Trump, a revolution that has threatened (and may yet end) American democracy.

If generative AI does to white-collar workers what globalisation did to our blue-collar cousins, we should anticipate even wilder political chaos. Knowledge workers are history’s most reliable revolutionaries. The popular notion that rebellion is fomented by pitchfork-wielding illiterates is wrong. The French Revolution was led by disaffected lawyers and journalists. So was the Russian Revolution. So was the Chinese Revolution. The political disturbances of the early 2010s in Turkey, Bulgaria and Brazil were all led by the angry middle classes.

An interesting paper, Aspiring for Change: A Theory of Middle Class Activism, published by academics at Hong Kong University in the aftermath of the (bourgeois-led) umbrella protests of 2014 found that across 78 countries middle-earners were more likely to participate in political unrest than those on smaller incomes.

Why? Well, the middle classes are more politically engaged. They have more time and more money. They are also measurably less cynical about politics than those on the lowest incomes, who tend to believe that one regime will be as bad as another; revolutions require hope. Most importantly, the revolutions of the past remind us that status is just as potent a historical force as money. A social class that is losing prestige is more volatile than one that is simply poor.

The historian Peter Turchin sets out a theory of political unrest in his forthcoming book End Times (precisely the sort of cheerful title that catches my eye when I’m moping around in The Times’s books cupboard looking for ideas).

Turchin argues that political disorder correlates with a phenomenon he terms “elite overproduction”. When society trains too many citizens for too few positions of cultural and political power (eg in government or the media) it creates a new class of resentful “counter-elites” who are prevented from taking up the places at the top of society for which their educations have prepared them. Such people tend to be violently and destructively hostile to the system, which has barred them from the power and influence they believe they deserve.

Perhaps no students ever have been as intensively prepared for elite knowledge work as those studying in today’s high-ranking universities: the expensive educations, the internships, the sacrifice of social and sexual life to brutal hours in the library. But these are precisely the people who may be about to graduate into a world that has no need for them. If the worst happens, they are going to be angry.

One of Turchin’s more eccentric notions is that history can be mapped as a series of cycles of stability and disorder. It’s hard to restrain one’s scepticism when confronted with confident line graphs purporting to reduce centuries of complex political, economic and cultural change to a pattern of scary plunges and benign upward swellings.

But, spookily, Turchin has long had the 2020s marked out as an age of instability. Even before anyone had heard of Chat-GPT. See you on the barricades, comrade.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout