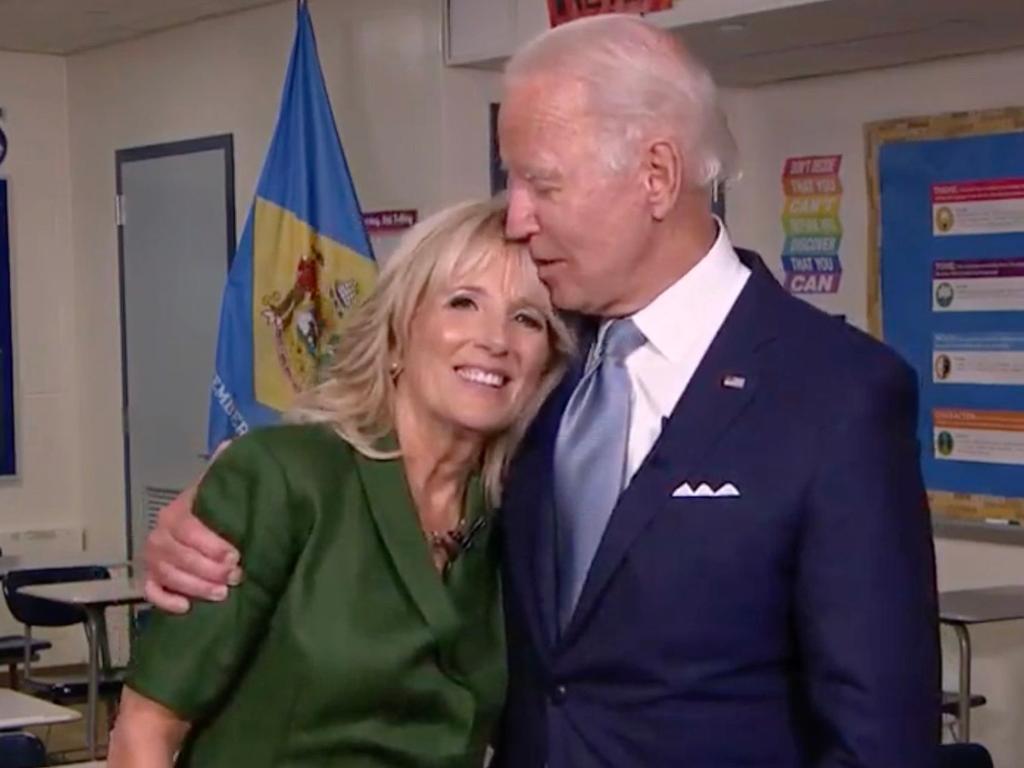

What Joe Biden’s foreign policy would mean for the world

Global summits, bringing US troops home, an end to Trumpian rhetoric look to be on the cards if he takes the White House.

Joe Biden plans to try to turn the clock back on America’s international relations to the pre-Trump era with a “global summit for democracy” aimed at restoring US leadership in a new drive to advance human rights and combat corruption and authoritarianism.

Another flagship pledge is to convene a “climate world summit” within his first 100 days in office “to directly engage the leaders of the major carbon-emitting nations to persuade them to join the US in making more ambitious national pledges”.

A Biden presidency would also pursue an extension of the new Start treaty with Russia to limit nuclear warheads without China’s participation, as demanded by the Trump administration, as the original agreement heads towards its February expiry date.

Summits with traditional allies will be back under a Biden presidency in contrast to the attempt at bilateral rapprochement with adversaries such as China, Russia and North Korea that dominated President Donald Trump’s foreign adventures.

Treaties will be back, too, with the clock reset to erase the Trump effect by returning America’s signature to the Paris climate accord “on day one”, the Iran nuclear deal “if Tehran returns to compliance”, and affirming categoric US support for NATO’s Article 5 pledge to come to the aid of an ally under attack.

Back to Obama

If Biden’s approach to foreign policy all sounds rather familiar, that is because it mainly seems to involve returning to the agenda of president Barack Obama.

However, beyond an overhaul of Trumpian rhetoric and a flurry of top-level conferencing and document signing, there is little surprise that conservative commentators remain unconvinced that all that much will really change on the ground.

“We have seen this act before,” says James Carafano, director of the Douglas and Sarah Allison Centre for Foreign Policy Studies at the Heritage Foundation, a right-wing think tank based in Washington.

“Obama swept in, he was going to make the world wonderful and he got a Nobel peace prize and what did he do? In the first two years he had a foreign policy that was Bush-like, except he didn’t call it Bush’s policies,” he claims.

“And then he put his own policies in place and by the end of the Obama years, were the Europeans happy? Not at all. People forget about how critical people in Europe were of Obama’s last years. The Middle East? Every ally in the Middle East thought we were whack jobs. Were the Asians happy? No, they were all moving towards China.”

To the right, one of the most ridiculous Biden plans was to go back to the Iran nuclear agreement when, Carafano claims, the US had a stronger bargaining position after Trump’s withdrawal.

“I think the people who come in will take on Trump’s Middle East foreign policy, without the rhetoric,” he said. “The foreign policy/security team are very much mainstream Obama people, so even if their instincts were to ratchet back to the good old days they’re also not stupid people and they know that’s not really possible. There will be a massive rhetorical shift but where that actually plays on the ground I don’t know.”

On the biggest single challenge of China, he added: “China has become so aggressive in the last few years, and there is such bipartisan concern about this, there is no way (a Biden administration) can wish away the last four years.”

More support for Israel

Biden’s global team is likely to be headed as secretary of state by either Susan Rice, 55, Obama’s former national security adviser, or Biden’s own senior foreign policy adviser, Tony Blinken, 58, a former deputy national security adviser.

Both are cut from the same pragmatic cloth on the moderate wing of the Democratic party as Biden which has, for instance, been much more supportive of Israel than the left of the party.

Blinken said in June that a Biden administration “would not tie military assistance to Israel to things like annexation or other decisions by the Israeli government with which we might disagree”.

In a policy paper posted on his campaign website in May, Biden, referring to the boycott divestment and sanctions campaign, vowed that his administration will “firmly reject the BDS movement — which singles out Israel and too often veers into antisemitism — and fight other efforts to delegitimise Israel on the global stage”.

Biden also said that if elected president he will “sustain our unbreakable commitment to Israel’s security,” including “the guarantee that Israel will always maintain its qualitative military edge”.

Biden gave a speech to the influential America Israel Public Affairs Committee in 2013 reaffirming the US to its “longstanding, moral ... and strategic commitment” to Israel, declaring that “the only way to ensure” that the Holocaust “could never happen again was the establishment and the existence of a secure, Jewish State of Israel”.

In April he criticised Mr Trump’s “short-sighted and frivolous” decision to recognise Jerusalem as Israel’s capital without using it as part of a bigger deal but added: “Now that is done, I would not move the embassy back to Tel Aviv.”

There is also a Trumpian flavour to Biden’s pledge on bringing troops home. He has vowed “to end the forever wars in Afghanistan and the Middle East, which have cost us untold blood and treasure ... (to) bring the vast majority of our troops home from Afghanistan and narrowly focus our mission on al-Qaeda and Isis”.

Where he differs from Trump is in holding to the belief of a “two-state solution” for Israel and the Palestinians, a phrase rejected by the US plan unveiled in January overseen by Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law, which suggested a mosaic of Palestinian areas connected by dedicated road and rail links.

Refocusing NATO

Trump was criticised for his approach to NATO, seemingly wary of an overt recommitment to Article 5 and making aggressive demands for member states to pay more for their defence, but some see the result as a much better-funded alliance more focused on terrorism and cyber threats.

Biden’s policy does not essentially sound much different. It involves “keeping NATO’s military capabilities sharp, while also expanding our capacity to take on new, non-traditional threats like weaponised corruption, cyber theft, and new challenges in space and on the high seas (and) calling on all NATO nations to recommit to their responsibilities as members of a democratic alliance”.

Biden’s Iran policy is thin but hedged carefully to commit to re-signing the nuclear agreement only if “Tehran returns to compliance” — seen as a handy get-out clause. There is no word on whether he would at all wind back Trump’s maximum pressure campaign that has brought the Iranian economy to its knees.

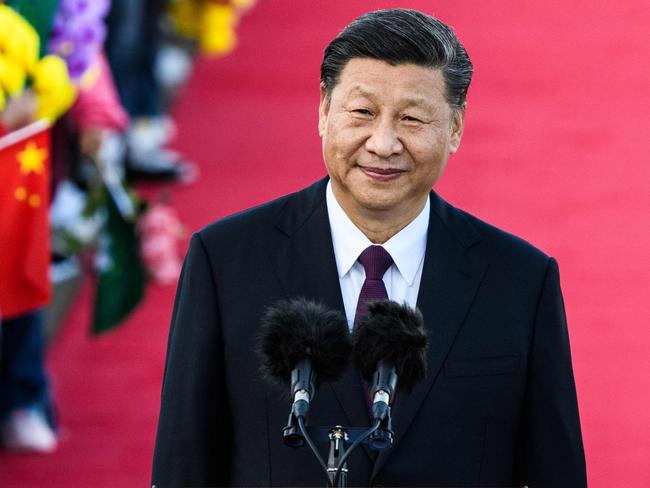

Relations with China

The biggest question mark over how Biden would deal with a global challenge is with China, which he notoriously played down on the presidential campaign trail in May last year. “China is going to eat our lunch? Come on, man,” he exclaimed, after saying that not a “single solitary” world leader would trade the problems the US faces for those confronting China.

He argued that Beijing had its hands full with its own domestic and regional problems, such as tensions in the “China Sea” and the “mountains ... in the west” although it was unclear to which mountains he was referring. Perhaps it was a shorthand for the repression of the Uighur population.

Since then the advent of the coronavirus, the collapse of Trump’s trade-based diplomacy with China and his administration’s aggressive rejection of Chinese technology companies has further soured relations with the US and raised the stakes.

Michael Carpenter, managing director of the Penn Biden Centre for diplomacy and global engagement, Biden’s own think tank in Washington, told The Times that dealing with China was ripe for the kind of alliance and consensus-building the former vice-president believes in, adding an imperative for concrete results from all the grand summitry he is planning.

“One of the keys to his approach is to put our alliances and partnerships with democratic countries at the very forefront of his foreign policy agenda because we only solve the world’s challenges by working with and thorough our partners and allies. The notion of ‘America First’ is a complete fallacy that often results with us being the ones isolated and not achieving our interests,” he says.

“When you think about confronting China, for example, to do so effectively given how clever the Chinese are and how ubiquitous they are around the world with their interests and their economic machinery, it only makes sense when you bring together European allies, the Japanese, South Koreans, Vietnamese and others together.

“There are obviously some democratic nations that are a little bit challenging to deal with like India and Brazil in particular given that they have demagogic nationalists in power but obviously we would work with them too, those are very important countries with whom we absolutely have to be working to contain China’s influence.”

Countering Kim

Biden has said he will work with China where necessary, such as to return to a more orthodox diplomacy with North Korea than Trump’s attempted love-in with Kim Jong-un. The exchange of adoring letters between the pair seems to have dried up after the collapse of face-to-face talks over Kim’s demand for sanctions to be lifted in return for minimal steps towards the US goal of denuclearisation.

Pyongyang does not seem fond of Biden after he accused Trump of granting Kim too much legitimacy. The dictatorship’s official news agency in November called him a “rabid dog” that “must be beaten to death with a stick” for “reeling off a string of rubbish against the dignity” of Kim’s leadership deserving of “merciless punishment”.

Ted Galen Carpenter, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank in Washington founded by Charles Koch, claims a Biden administration would fare worse than Trump. “Contrary to the conventional wisdom, Joe Biden would be less, not more, likely than Trump to reduce tensions with Pyongyang,” he wrote in National Interest this week.

“In January Biden stated that there was ‘no way’ that he would agree to meet North Korean leader Kim Jong-un without preconditions. He was referring to tangible steps from Pyongyang to reverse its nuclear weapons and ballistic missile program ... About the best we can hope for from a Biden presidency is a continuation of the sterile, futile policy over the decades of demanding that Pyongyang return to nuclear virginity. A worrisome possibility is that he succumbs to pressure from militant hawks in both parties and adopts a dangerously confrontational stance toward Pyongyang.”

Biden has often been cautious about US military intervention — he cautioned Obama against the bombardment of Libya in 2011 — and the US military was more active under the Obama presidency than Trump’s.

When it comes to Europe, Carpenter, from Biden’s think tank, set out five “ways to fix America’s broken relationship” in an article for Politico.

He called for an end to the trade war with the EU, commitment to fight climate change, refocusing of NATO on “neglected theatres like the Arctic and Black Sea, where Russia is increasingly active”, a greater push against authoritarian regimes for example by developing a “democratic 5G consortium” to counter China, and said finally that “both sides of the Atlantic need to recommit to defending democratic values and reject the practice of muzzling independent media, dismantling democratic checks and balances and politicising law enforcement, the judiciary and intelligence agencies” as well as “co-ordinated anti-money laundering efforts ... and a commitment on both sides of the Atlantic to finally ban anonymous shell companies”.

After Obama began to focus on Asia, it is one region where it seems a Biden foreign policy would differ from the Trump or Obama approach. Unlike both recent presidents, it is a region for which Biden has a strong affinity and affection, not just because of his strong feelings about his maternal Irish roots but because of his long-standing appreciation of the transatlantic alliance.

The Times