West prepares for panic at home if Vladimir Putin resorts to nuclear strike

A strike in Ukraine would threaten chaos at home but one expert says it may not be as bad as we fear.

Western countries are making contingency plans to deal with the chaos of a nuclear war in Ukraine, officials said on Friday, as the threat grew of a battlefield strike by Russian president Vladimir Putin.

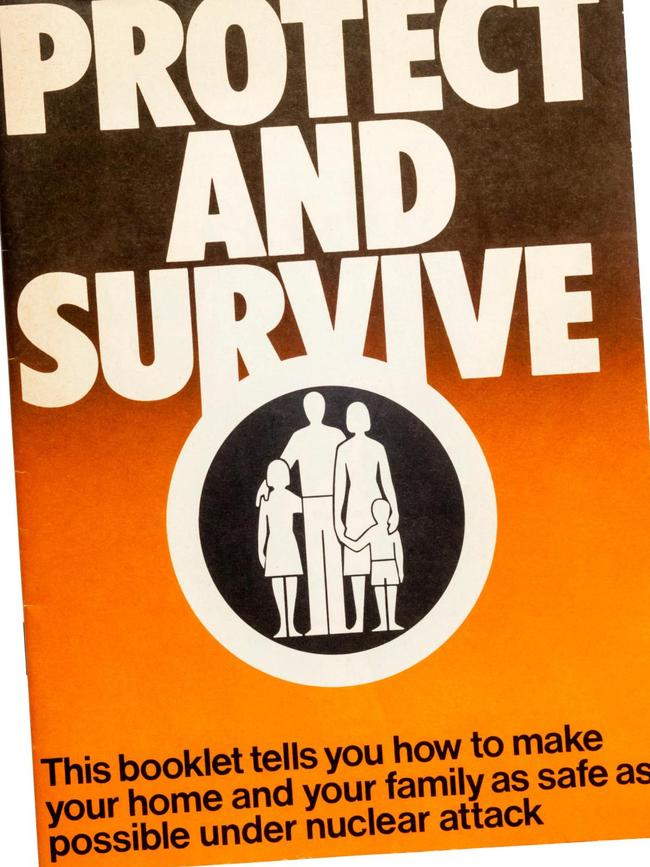

The measures could include issuing leaflets on how to survive an attack or ways to ease panic buying amid fears that the fallout could reach Europe and beyond.

Putin’s recent threats to use nuclear weapons have set off alarm bells across NATO, with the alliance holding talks behind closed doors on how it will respond to such an attack.

Some observers believe there is a realistic prospect of the Russian leader using a tactical nuclear weapon against Ukraine, either firing it on land or into the Black Sea.

Asked if there were contingency plans to deal with the fallout of a strike, a western official said: “As you would expect, the government is conducting prudent planning for a range of possible scenarios.”

The proposals could be redolent of those in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the British government issued “protect and survive” booklets that described “how to make your home and your family as safe as possible under nuclear attack”.

The western official went on to condemn Putin’s “deeply irresponsible comments about nuclear use”. He said: “Any use of nuclear weapons would break a taboo that has held since 1945 and would lead to severe consequences for Russia as well as everybody else.”

Strategists warn of at least two outcomes from a nuclear war with Russia.

The first is that a desperate Putin attacks a big city, causing untold death and destruction. Once again the world would be reminded of the horrors of nuclear weapons.

The second is that he attacks somewhere else, a region less populated, and it doesn’t seem so bad after all.

“The public tends to look at the use of nuclear weapons as a cinematic, extinction-level event,” said Stephen Herzog, a senior researcher in nuclear arms control at ETH Zurich, a Swiss university.

“What, though, if we’re talking about the use of a small, tactical nuclear weapon over a forest or Snake Island?”

The outcome might feel different. Casualties could even be low.

The question for Herzog and other researchers is: would the world, especially China and India, still condemn it? Or would the nuclear taboo, which has kept us safe for 70 years, be broken? Herzog fears it could put us on an “escalation ladder”.

At few times since 1945 have we been closer to putting our foot on the first rung of that ladder.

In television addresses Putin has pointedly cited the American use of atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki as a precedent. He underlined that Russia would use “all available means” to defend its territory – which the Kremlin has redefined to include the annexed parts of Ukraine.

Ukraine’s President Zelensky repeated, on Friday, his promise to regain every bit of land lost to Russia as he marked Ukraine Defenders’ Day.

In Washington, President Biden warned that the world was closer to nuclear conflict that at any time since the Cuban missile crisis.

He is not alone in that view. “Nuclear deterrence is running on fumes,” Herzog said. He has written an editorial in the journal Science calling for a rethink of last century’s ultimate defensive doctrine.

Without going into detail, Jens Stoltenberg, the NATO secretary-general, has said that Russia would face “severe consequences” if it used any nuclear weapons in Ukraine.

Although nuclear powers have always been cautious to guard their precise doctrines in case the other side should read their hands, French president Emmanuel Macron hinted this week that France would not use its independent deterrent against Russia if atomic missile strikes were ordered on Ukraine.

Among those who consider these problems analytically, there is a way of looking at nuclear conflict as a fixed low probability risk. In any one year, the chance of a major war is low. But roll the dice enough for long enough, and it becomes inevitable.

In the journal Global Policy, Matthew Rendall, a lecturer in international relations at Nottingham University, this month wrote a paper entitled: “Nuclear war as a predictable surprise.”

His argument is that we have become complacent after surviving the Cold War. “Probably we will get through this OK,” he says. “But the worry is, ‘probably’. If we start doing this sort of thing repeatedly, my fear is in the long run we’re not going to get lucky.”

Matthew Bunn, a foreign policy professor at the Harvard Kennedy School in Massachusetts, estimated that the risk of nuclear conflict in Ukraine was 10 to 20 per cent.

Rendall said the nuclear taboo had been a key mechanism to keep us safe. “Nuclear weapons have become something you don’t really put on the table,” he said. “It’s like cannibalism. If you get hungry you don’t perform a cost-benefit analysis. You don’t think, should I go out and catch somebody and eat him?”

He said if a nuclear weapon were used “my hope would be that … Russia would become persona non grata, the way South Africa was under apartheid. But what if that doesn’t happen?”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout