West can stop the world falling for Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin

This is nothing to do with friendship or ideals. Xi will stand by Putin, however many Ukrainian cities are destroyed, regardless of the countless war crimes committed, because keeping Russia close is in China’s national interest. He may talk peace with Zelensky but ultimately he will do whatever it takes to keep Putin going.

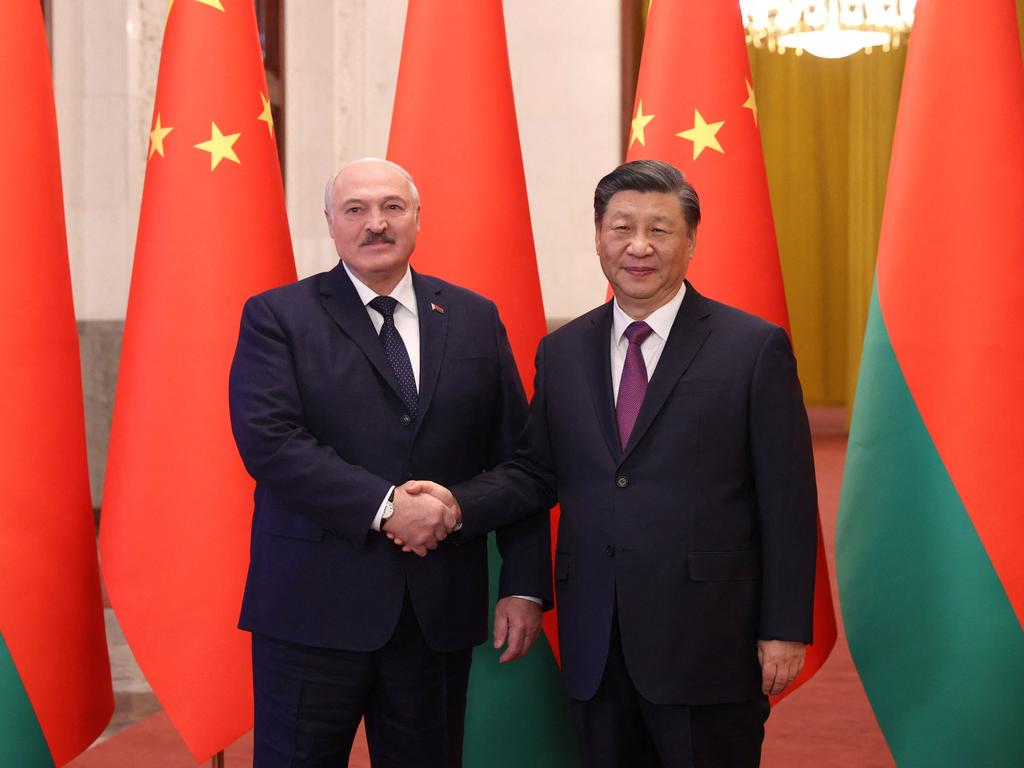

In the West we are also acting in our interests by supporting Ukraine, for if Russia could get away with destroying a European country, we and our allies would need vastly greater defence expenditure for decades to come. But we also believe that we are acting in the wider interest of humanity. To us, the defeat of armed aggression and the upholding of human rights are vital principles. The kidnapping of children and the torture and execution of Ukrainians are crimes that cannot be committed with impunity. The sight of Xi and Putin in Moscow sharpens our view of an intensifying struggle between democracy with values, against autocracy with tyranny.

According to polling last autumn, 87 per cent of the 1.2 billion people who live in liberal democracies held a negative view of Russia; 75 per cent also thought negatively of China. But the two dictators meeting this week are playing to a different audience: the views of the more than 6 billion people who live outside our democracies are the exact opposite. Months into Moscow’s murderous war, large majorities thought positively of Russia in South Asia (75 per cent), Francophone Africa (68 per cent) and southeast Asia (62 per cent). What has become known as the global south, including many increasingly important and populous states, just doesn’t think our way.

To us this can seem so irrational that it’s hard to accept. And we console ourselves that 141 countries have voted in the UN to condemn Russian aggression. But only about 40 of those have done anything about it, with sanctions or assistance to Ukraine, and the abstentions included some of the world’s most consequential nations. India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, has said it is not a time for war, but his country has stepped up purchases of Russian oil. President Lula of Brazil has said it takes two to fight. South Africa has hosted exercises with Russian warships.

We have to adjust to the idea that most of the world does not see things our way. As China builds diplomatic prestige in the Middle East through bringing Saudi Arabia and Iran closer, and expands its list of client states in Africa, Asia and Latin America with grants and loans – no questions asked – the West will need to guard against the danger of being globally outmanoeuvred. It is entirely possible that our values will ultimately triumph in Ukraine, and we should fervently hope so. But we might then find that our interests are under threat across much of the rest of the world.

While the concept of the global south is a generalisation, it is true that in many countries an unflattering view of the West prevails. Our history of empires is remembered, and we stand accused of hypocrisy – who was it who invaded Iraq? We care about conflicts in Europe but much less about those elsewhere, such as recent slaughter in Ethiopia. Our view of a binary choice between democracy and autocracy is seen as self-serving, and ceaseless Russian propaganda is believed, from claims of attacks on Russian civilians, to NATO aggression, to US experiments with biological warfare labs in Ukraine.

Above all, countries of the global south will act in their own national interests, just as they perceive us to be doing. Caught between big powers, they hedge their bets. In a world of sanctions, there are new ways to make money, through buying cheap Russian oil or getting expensive goods to Moscow’s shops. Meanwhile, they will buy Chinese warplanes, knowing that ours are subject to strict export controls; and accept Chinese loans, even at the risk of being caught in a debt trap, because of lack of alternatives. Their interest lies in a multipolar world, where they trade with all, rather than a bipolar world where they are dependent on the West.

Western leaders are starting to focus on this issue. Emmanuel Macron has spoken of being “shocked by how much credibility we are losing”. Joe Biden has presented at the G7 his plan for “Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment”. Last week’s update of UK strategy puts the problem in official-speak: “Systemic competition is developing into a highly complex phenomenon that we must navigate with an understanding that not everyone’s values or interests consistently align with our own.” In plain language, that means we will increasingly have to choose between absolute adherence to our principles or pragmatically making friends. In foreign policy, an agonising period is on its way.

We can nevertheless do more, without breaching any principle, to step up both communication and genuine partnership with the global south. Tactically, we should be asking leaders from the Baltic states and eastern Europe to take democracy’s arguments on tour: let people hear from Tallinn, Vilnius and Bratislava rather than Washington and London what it is like living next door to Putin, how NATO is a defensive alliance and why atrocities in Ukraine matter to the whole world. That should be backed by more ambitious actions to fight disinformation globally.

Strategically, more can indeed be done to align others’ national interests with our own. In contrast to the hoarding of vaccines during Covid, more aid should be devoted to sharing the benefits of science and innovation, from which many poorer nations will be at risk of being left out. In Africa, the West needs to pursue a more energetic and co-ordinated effort to stabilise the Sahel region, rather than leave governments to depend on Russia and its mercenaries.

Globally, we need to transform finance for climate change and energy transition, such as with the reforms of the World Bank proposed by Germany. We could be open to accepting much of the “Bridgetown agenda” advanced by Barbados, to mobilise trillions of dollars to help developing countries.

Twenty years ago, we tended to think in the West that everyone would become like us, from Baghdad to Beijing. Now we can see that many will not do that. Considerable energy, new policies and a changed world view will be needed to adapt to this reality.

The Times

Why is Xi Jinping in Moscow? He is there because if you are China, pursuing a 21st-century strategy, it is essential to have Russia on your side. Preferably not just on your side but bound to your side, with no option but to build future gas pipelines to China, supply uranium, share military and space technology and ensure that in the intensifying rivalry with the US, China can never be surrounded. Xi’s ideal is to have Putin as an ally but also a dependant, and that is exactly what he has become.