The possibility that the US Supreme Court may finally overturn Roe v Wade, the 1973 ruling that legalised nationwide abortion, has been greeted with the usual fabricated panic by progressives and their media allies.

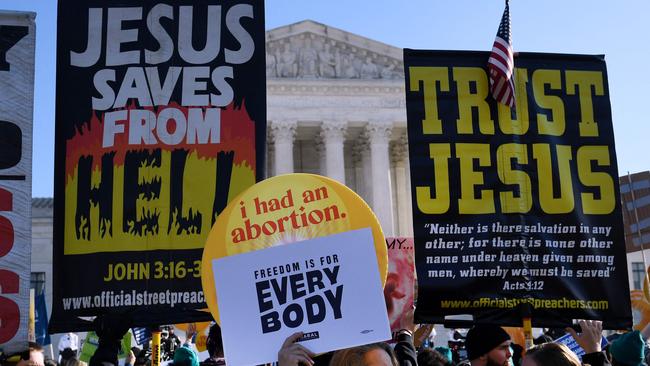

As the nine justices listened on Wednesday to arguments in a case that would restrict abortion in Mississippi, with some exceptions, to pregnancies up to 15 weeks gestation, airwaves hummed and networks crackled with the familiar lurid warnings that the US was heading back to the days of coathanger self-mutilation and female enslavement.

Writing in the Financial Times last week, Katie Roiphe, who goes by the Orwellian title of “director of the cultural reporting and criticism program” at New York University, suggested that a decision by the court to overturn Roe would be akin to denying women in the US the right to possess their own money.

In an age when rabid extremism substitutes for reasoned argument, and with the nation’s highest court pondering the most serious challenge to the half-century old legal framework that controls abortion, it may still be worth trying to put the seemingly never-ending American abortion debate into some sort of reality-based context.

First, the US has among the most permissive abortion regimes in the world. Only seven of 198 nations analysed in a recent report allow elective abortions after 20 weeks of pregnancy – the US among them. Contrary to the usual depiction of America in the British media as some kind of hag-ridden theocracy in which gun-toting white supremacists enforce medieval social mores on a cowed population of women and minorities, the US finds itself on this issue, as on many others, at the very progressive, state-mandated extreme, in the company of countries such as China and North Korea.

The Mississippi act before the court would do no more, in fact, than bring that state’s law into line with the prevailing legal conditions for abortion in 39 of 42 European countries, including such notorious abusers of women as Germany and Denmark.

So the idea that the present legal framework in the US is the only way to protect a woman’s right to a safe and legal abortion, tempered by widespread public disquiet at the destruction of relatively late-term foetuses, is palpable nonsense, and demonstrated to be so by the practice of at least 191 other countries that don’t resemble the Republic of Gilead.

Second, the existing legal framework is, as even some of its more honest proponents acknowledge, an irrational mess. Roe v Wade itself, as no less an authority and progressive icon than the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg acknowledged, was a vast confection of social and political objectives dressed up as judicial reasoning.

Its main provision barred states from passing laws that would outlaw abortions before the end of the first trimester, left vague what should happen in the second, and blocked most abortions in the third. It reached that oddly specific interpretation of the US constitution by legal reasoning citing an earlier case that ruled that the Bill of Rights had created “emanations” of protection that involved “penumbras” of rights.

Notwithstanding its intellectual deficiencies, the thrust of the ruling was upheld but refined by the 1992 Planned Parenthood v Casey decision, in which the court ruled that no state should place an “undue burden” on a woman’s right to seek a termination and that foetal viability, rather than semester status, should determine the limit of allowable abortions.

As John Roberts, the present chief justice, argued in gently probing questions of the lawyers this week, these two legal principles aren’t consistent. Foetal viability is now achievable at as little as 22 weeks, but the “undue burden” rule could be applied at an earlier stage. Is it an undue burden to require a woman to decide to have an abortion by 15 weeks? Evidently not in the vast majority of European countries.

So some tightening of abortion laws, which the “foetal viability” standard appears to forbid, seems not only reasonable but within the framework of at least part of the existing law. Therein lies the thorny challenge for the court and in particular for the six conservative justices who, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, seem to want to permit states to take, if they wish, a more restrictive approach.

It appeared this week that the chief justice was attempting to thread the needle – allowing more restrictive laws in keeping with practice in much of the world, while not fully overturning Roe, and thereby allowing states potentially to place even tougher restrictions on abortion or outlaw it altogether.

The other five conservative justices seem more open to the idea, and convinced by the logic, of simply negating Roe. But even some of them may recoil at the implications of a decision that could see abortions banned in some states and doctors who perform them subject to criminal penalties.

So the likeliest outcome may be some kind of limited ruling that is provisional in effect: one that upholds Mississippi’s law, thereby dispensing with Roe’s viability reasoning, but does not amount to a blanket invitation for all states to immediately repeal the right to abortion. Efforts by states to roll back abortion rights further would then be considered in subsequent cases, and a new legal framework established, with minimum federal stipulations on the kinds of laws that would be upheld.

All this may well amount to substituting one kind of legal mess for another. The original sin of Roe v Wade was that it took one of the most contentious issues of the age out of the hands of voters and their elected representatives and made it solely a justiciable issue. But denying the people, state by state, the right to make their own laws merely made the issue more contentious.

The present court may wisely cede some of its authority back to the voters. But we can abort the hysteria. It won’t turn America into a Divine Republic.