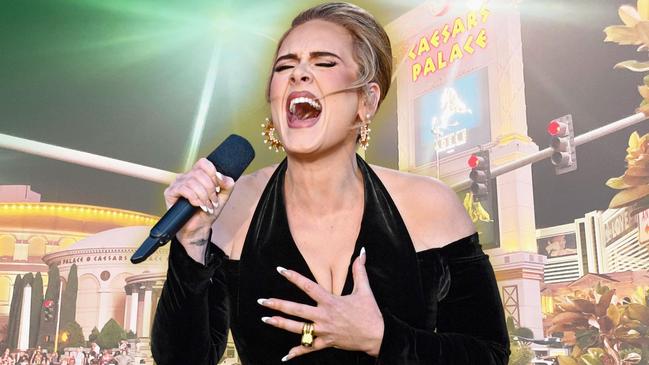

Voice, glamour, attitude: Adele’s making of a diva

As the singer opens at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, a fascinating appraisal looks at how she ranks against the greatest female performers.

On Friday night in Las Vegas (3pm Saturday, AEDT) Adele opens at Caesars Palace.

It is, of course, an important moment for western civilisation.

Yet many questions surround her five-month residency. Will she actually do the gigs this time, unlike in January, when she cancelled the lot? Will she avoid a punch-up (or, let’s be accurate, what was described as a “butting of heads") with her set designer?

Has she been able to rehearse without constantly being “in the middle of an emotional shout-out” with her sports agent boyfriend, Rich Paul – as Caesars Palace insiders say they witnessed last time round?

And, more intriguingly, how will the residency fit in with her new aspiration to study English literature for a university degree?

Will her famously extended monologues between songs now be peppered with allusions to The Waste Land? The punters who have paid up $70,000 a ticket surely deserve nothing less than the complete Paradise Lost, with footnotes.

All those incidental questions, however, are overshadowed by an even more fascinating one.

Dedicated Adele watchers already detect telltale signs. Divas must appear like goddesses – after all, that’s what the word means in Latin – and when Adele sang at Hyde Park this summer she certainly did that, what with the long black dress, the pearls, the lusciously styled hair, the flames, the showers of confetti and fireworks that marked her last exit.

Times rock critic Will Hodgkinson described her that night as “like a modern Barbra Streisand” but I would go further. To me this very theatrical extravaganza suggested the finale of some fantastical 17th-century opera, where a great deity descends from heaven and, with one imperious blink of her false eyelashes, conjures up a happy ending for all present.

All dates will be rescheduled

— Adele (@Adele) January 20, 2022

More info coming soon

💔 pic.twitter.com/k0A4lXhW5l

Musically, too, Adele has evolved from simplicity to grandeur.

You can actually play her songs quite effectively with four or five chords on a piano, and that’s how she mostly used to present them – unvarnished and heartfelt, like the best pub singer you’ve ever heard.

Now, though, by the time they reach the last chorus they tend to be wrapped around with Hollywood-style swooping strings, underlining and magnifying every anguished twist of the lyrics and the throbbing passion of her voice. Again, it’s a classic diva tactic, connecting the modern-day pop superstar orchestrally with the operatic prima donnas of the 19th century, where the term diva originated.

True divas, however, need more than glamorous frocks and lavish orchestral backing.

In particular, two psychological traits are essential. The first is that they must have encountered unhappiness or setbacks in their lives and then flaunt the emotional scars like badges of honour.

In his fascinating book, Charisma in Politics, Religion and the Media, David Aberbach suggests that the public figures with the greatest mass appeal – such as Hitler and Marilyn Monroe (to take two extremes) – are likely to be individuals damaged by unstable or unpleasant childhoods.

He argues that this damage, when accompanied by exceptional gifts of performance or communication, is what makes them not just magnetic but irresistible to millions of followers, who can sense their own troubles mirrored in their heroes and heroines.

Look at the greatest divas in history and you see abundant evidence of that. From Edith Piaf to Billie Holiday to Maria Callas (not just a diva but “La Divina” to her fans), we find characters whose fractured childhoods and subsequent struggles greatly deepened their popular appeal.

When Callas sang, the audience knew that every note was coloured and infused by a lifetime of turbulence and intemperate passions, culminating in one of the most devastating celebrity humiliations of the 20th century: when the Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis dumped her to marry Jackie Kennedy.

Adele hasn’t been through the same magnitude of trials and tribulations (though her single-parent upbringing was far from plain sailing), but she is canny or intuitive enough to know that by emphasising her setbacks and sorrows in her stage appearances – by showing that she understands rejection and self-doubt – she is enabling millions of ordinary people to feel a connection with her.

So she has that first essential diva quality. She has suffered, she makes no secret of it, and her legions of fans love her for it. The second vital trait, however, is much harder for a basically pleasant, friendly person such as Adele to achieve, and certainly harder for those around her to deal with.

It can be labelled in many different ways. Charitably a diva may be said to have an “uncompromising attitude” or a “quest for perfection”.

Uncharitably she is likely to be accused of arrogance, high-handedness, rudeness and even megalomania.

It’s as if a diva needs to compensate for the bad things that have happened to her by wrapping herself in an impregnable cloak of entitlement. Demands that seem spectacularly unreasonable to other people seem perfectly logical in her mind. “Don’t talk to me about rules, dear,” Callas snapped. “Wherever I stay, I make the goddam rules.”

Those demands can often be so ludicrous as to be hilarious.

Kathleen Battle, the American operatic soprano fired by the Metropolitan Opera in New York for subjecting every other cast member of a production to what was described as “withering criticisms”, once allegedly phoned her agent from the back of a limousine to demand that he phone the chauffeur and instruct him to turn the airconditioning down.

Mariah Carey famously insisted on being surrounded by 20 white kittens and 100 doves, just to switch on the Christmas lights at the Westfield shopping centre in west London (she relented when told it was against health and safety rules).

Sometimes, however, you sense that the diva’s demands are fuelled by a self-righteous fervour so powerful that it terrifies all who have to work with her. Such divas are not confined to showbiz. Without question the most diva-like person I have ever met was the imperious and visionary architect Zaha Hadid.

The first time I interviewed her she showed up 90 minutes after the agreed time (“she runs on Zaha time”, a minion explained) and then turned on such a gush of charm that I almost floated home afterwards.

Yet when she won the gold medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 2016, even the official citation described her as “scary”. I once asked her why she had run into such opposition throughout her career. “I am demanding, I am Iraqi, I am a woman,” she replied, as if those 10 words explained everything.

Actually, I think they did. As with the second most diva-like person I have encountered – the opera singer Jessye Norman, who could be vile to underlings and journalists alike – everything makes more sense if you factor in the decades, early in her life, when she was on the receiving end of institutionalised and personal misogyny and racism (in Norman’s case, growing up as a black child in the segregated American South).

Even so, it’s not surprising that the word diva has taken on a pejorative meaning in recent decades. To call someone a “real diva” is not usually, these days, an indication that you think she’s a conjunction of the goddess Venus and Mother Teresa. Quite the opposite.

“The word has gone from meaning ‘high-class’ to ‘high-maintenance’,” we are told on that indispensable guide to enlightened modern thinking, the Duchess of Sussex’s Archetypes.

Indeed, Meghan goes further. Calling someone a “diva” is, for her, not just insulting, it’s also a way of “tearing down” any female with ambition, talent and determination.

Unfortunately for Meghan, her guest on that podcast – Mariah Carey, no less – provides a devastating observation of her own.

“You give us diva moments sometimes, Meghan,” she tells her host. This causes no small agitation in the Sussex soul. “That’s not true, why would you say that?” she responds in apparent bewilderment.

Then, however, she thinks she understands the confusion. When Carey called her a diva, she tells her listeners, she was actually talking about Meghan’s “fabulousness”. “She meant diva as a compliment,” Meghan concludes. To which, I imagine, several million people round the world must have responded, “Oh really?”

Which only goes to prove: nobody is better at seeing through a diva – at recognising the pretentiousness and posturing and artificiality of all that hauteur and grandeur – than another diva.

In this respect, the undisputed world champion was Judy Garland. Attending the same Beverly Hills party as Princess Margaret, she was approached by a lackey sent by the princess. Margaret, he said, wished Garland to entertain the assembled company with a song. “Tell her I’ll sing if she christens a ship first,” Garland replied in a voice that cut across the room like a razor across a throat.

That was mild, however, compared with Garland’s demolition of her rival diva, Marlene Dietrich, on a TV chat show.

Garland recalled how she was sitting in a Paris hotel lobby with Noel Coward when Dietrich appeared carrying her new record. “Would you like to hear it?” Dietrich asked.

“Well, we could hardly say, ‘No, we don’t wanna hear your record,’ ” Garland said, “so she put it on. And it was nothing but applause. Just applause! Sometimes the applause would vary, so Marlene would say, ‘Oh, that’s the applause for me in Frankfurt … that’s Berlin.’ But there wasn’t one note of music. Eventually Noel turned to me and whispered, ‘I hope there isn’t a B-side.’ But there was.”

Such a recording was, of course, the ultimate validation for a diva like Dietrich: nothing but the continuous adulation of her doting fans.

On that basis, perhaps we should wait a couple more years for proof that Adele has achieved diva status.

If her next album (presumably titled “35”) has nothing but applause on it, we will know for certain that she has finally got there.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout