Crunch time for Oxford’s COVID-19 vaccine

We won’t have to wait too much longer to learn whether the vaccine set for an Australian release is effective or not.

There are perhaps half a dozen people in the world who have any idea how the most important scientific trial in Britain this century is going. And even they don’t know the most important piece of information in it.

But one day soon, they will have enough data. They will have noted that 150, or maybe even fewer, of the 20,000 volunteers involved in the Oxford University vaccine trial have been symptomatically infected by the coronavirus. It will be time to start assessing whether it works sufficiently well or not.

That is when a human being will at last be allowed to look at the piece of information that will decide whether you can book a holiday or plan a wedding: how many of those 150 people who got Covid-19 did so after receiving the vaccine, and how many after taking the control?

The Australian government has an agreement with the British pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca, which is developing the vaccine with Oxford, to secure at least 25 million doses of the Oxford vaccine if it passes clinical trials. If it does, Australia will manufacture and supply vaccines and will be made available for free. The project could deliver the first vaccines by early 2021.

Since the start of the pandemic, we have been told that a vaccine is our exit strategy. But the process of approving a vaccine is not quite so simple.

Britain has bet heavily on one vaccine: the Oxford vaccine. In the portfolio of technologies we have bought, only one other, from Pfizer, could be ready by winter, but we have not bought enough doses in advance to cover the whole country.

Ultimately, though, whichever contender is successful (assuming that one is), the largest mass-vaccination program in history will be kicked off by half a dozen experts following the infection of just a few dozen volunteers.

The data monitoring board, that handful of scientists, is not running the trial. Their job is to work at arm’s length and assess information dispassionately when it comes in. They are looking at the trial in three countries: Brazil, the UK and South Africa. In the US, where 30,000 volunteers have been enrolled, the trial is still paused because of safety concerns. The trial protocols have only been published for the US arm of the Oxford vaccine trial but The Times understands that they are similar in the UK.

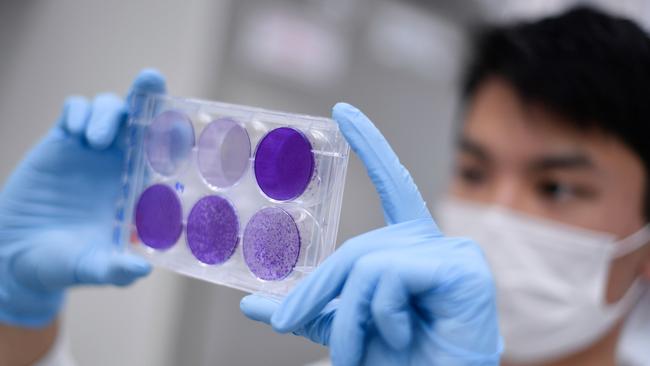

Across the three countries, 20,000 volunteers each receive either one or two doses of a vaccine. Half of the cohort will get the real vaccine, half the meningitis vaccine – chosen because it produces similar soreness and side-effects. Then each of them is quizzed weekly about symptoms and swabbed for infection.

In the US, assuming that the trials restart, the first point at which they will consider assessing the effectiveness of the vaccine is when 75 people have had a symptomatic infection of coronavirus. That is when the data monitoring board can take a peek to see whether there is a sign that it is working. By the time 150 are infected they will start to have an answer either way.

With luck, they will find that none of those with symptoms will be in the group with the Oxford vaccine. It will have protected them perfectly.

WHAT IF IT’S NOT 100 per cent EFFECTIVE?

The macaques, alas, still got sick. Back in spring, six monkeys were given the Oxford vaccine and then deliberately infected with coronavirus. What happened next was the first evidence for many that this particular vaccine might not prove to be 100 per cent effective.

Compared with those who had not been vaccinated, the monkeys were significantly less ill, which is good news. But they were still infected, were still infectious and they still got ill – which is not. Those in the field were not surprised. Few vaccines offer anywhere near complete prevention of infection.

It is very likely, then, that some people will get the vaccine and still get sick. The regulators accept and expect that: provided that it prevents 50 per cent of symptomatic infections it will be declared a success. Better vaccines can come later: we have 2021 to get through.

What if, like the macaques, we get a different, but still useful, result? If it keeps us out of hospital, is that not enough? Peter Doshi, of the University of Maryland, is worried that wishful thinking could lead to fudging the results. “They could try and make lemonade out of lemons,” he says.

The trial, he argues, is not really able to answer the question of whether the vaccine prevents sickness. “If the trial is stopped after 150 events, the vast majority are going to be mild.”

This must be true, as most infections in general are mild. So if all we are looking for is a reduction of severity, we will have little to go on.

In the US, he is confident that if it does not meet 50 per cent efficacy it will be seen as a failure.

Here, however, Stephen Evans, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, thinks that regulators might consider the lemonade possibilities.

“The US tends to be prescriptive, while Europeans are a little more finger-in-the-air,” he says. “I think it is entirely possible that the UK may take that sort of thing into account. I think we could well see vaccines with lesser efficacy being used.

“It will then be vital to ensure that complete tracking of everyone who is vaccinated is carried out to ensure the vaccine is effective in actual use without serious adverse reactions.”

APPROVAL AND DISTRIBUTION

In ordinary times, says Steve Hoare of the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry, it can be months after a vaccine manufacturer submits trial results before they receive approval. “I suspect in Covid times that will be shortened,” he said.

Corners will not be cut – he is clear on that – but there is already a precedent for speeding things up. It normally takes months or years to get approval for a trial to run but the Oxford trial managed to get it in a week. “And, yes, it meant they were working 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” Mr Hoare says.

Around the world everything that was once being done sequentially is now being done in parallel, including vaccines, which are being made before they are shown to work. Astrazeneca will not disclose the location of the Oxford manufacturing site, except to say it is “local”. The Royal Society says that the 100 million doses Britain has ordered are being made in the Netherlands, the UK and India.

Even as approval processes are under way, there are plans in place to begin the distribution of doses. This means, said Penny Ward, from King’s College London, they can be ready to go from day one.

But not everyone will be able to turn up at their GP and expect to be vaccinated. The priority will be old people, sick people and people who deal with old and sick people. Last month care homes all received an email requesting details of key staff who would need a vaccine.

The rest of us will have to wait, and how long that is depends on which vaccine is successful first and whether it is one that we have bet on.

In a report this week scientists at the Royal Society suggested that the rollout of a vaccine could take as long as a year in the UK. Globally, it will be several years. Those familiar with the Oxford vaccine are more hopeful.

Three to five months after approval, if all goes to plan, they hope that the last adult in Britain will receive the last dose. Children, who were not in the trials, will not, but the hope is that they will benefit from adults’ herd immunity.

All of which means that if the Oxford vaccine is approved in early 2021 then you can probably feel safe booking your summer holiday. But it’s a big “if”.

Jack Sommers, who was jabbed with the vaccine candidate, said he had always thought timelines for the rollout were optimistic.

Mr Sommers, who lives in London, said that the Oxford researchers would not rush the trial.

“They email us all the time reminding you to tell them to remember to tell them if you go to hospital,” he told News Corp Australia.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout