Until our leaders bridge the great vaccine divide, no one will be safe

The Indian variant shows us we are only as safe as the least-safe country — and that should ring alarm bells for our leaders.

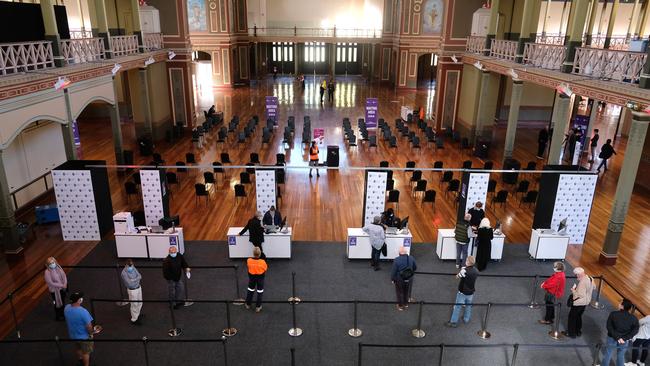

On Wednesday I emerged from a tent in a car park in Roehampton feeling invincible. It wasn’t as glam as the setting for my first Covid-19 vaccination — the Science Museum in London, where, slightly alarmingly, they found on their computer system a person in Blackpool with exactly the same name and date of birth as me — but joining the 50 per cent of the adult population in this country to have received both jabs still felt damn good.

Some of those queuing in the tent were fearful. I watched staff patiently explain the benefits (as well as the updated side-effects) to a trembling lady who said the rest of her family were against the vaccine but she had lost her aunt to the disease.

In the US they go one step further. In their drive to try to get 70 per cent of adults vaccinated by the Fourth of July, they are offering incentives such as free childcare and Xboxes, and the chance to win flights, cruises and a year’s supply of groceries. Krispy Kreme is handing out doughnuts while Budweiser is promising free drinks if the country reaches the 70 per cent goal. “Get a shot and have a beer,” declared President Biden.

This stands in stark contrast to the rest of the world, where vaccines are scarce and some countries yet to even start vaccinating. While we in the UK have done 50 per cent, worldwide the average is 5.7 per cent. While we debate whether Pfizer-BioNTech or AstraZeneca is better, some have no shots at all: they are what the World Health Organisation terms “vaccine deserts”.

As I got on my bike home, feeling humbled at what science has achieved so quickly, I also felt guilty. I might be over 50 but I am fit and healthy – why should I get the jab before doctors and nurses on Covid front lines in less fortunate countries?

The UK has so far carried out 66 million vaccinations. On the day of mine, 521,782 were done, which is more than have been done in a total in 66 countries, according to the Johns Hopkins University coronavirus tracker.

Of the 2.05 billion vaccines so far given worldwide, about 83 per cent have gone into the arms of citizens of higher and upper-middle-income countries, according to the WHO, and only 0.4 per cent have gone to lower-income countries. In Afghanistan, 0.38 per cent of the population is fully vaccinated. In South Sudan, population 11 million, just 9,744 people have received their first jab. Burkina Faso gave its first 200 shots on Wednesday. Eight countries have yet to start any.

What is fast becoming the Great Vaccine Divide is likely to be a focus of the summit of G7 leaders in Cornwall this week, with middle and lower-income countries increasingly angry at what they see as vaccine hoarding by the rich. Yesterday a group of aid organisations, scientists and senior politicians including Unicef, William Hague and Jose Manuel Barroso, the former president of the European Commission, called on G7 countries to share their doses and the UK as the G7 host to “show historic leadership”.

Barroso is chairman of Gavi, the global vaccine-sharing programme, which sounds like a good initiative but has so far shared only 76 million Covid vaccines. This was boosted last week with a commitment of 19 million vaccines from the Biden administration and now has pledges of dollars 9.6 billion. Even if these materialise (and they often don’t), this will mean vaccinating only 30 per cent — less than half what is needed for herd immunity.

As the Whac-A-Mole nature of Covid-19 has shown us, time is of the essence. The WHO has warned of an “abrupt 30 per cent rise” in cases in eight African countries in the past week, while vaccine shipments were at “a near halt”. In May, a study in The Lancet found Africa has the highest death rates among critically ill patients in the world. Less than 2 per cent of global vaccines have been administered on a continent that has seen about 4.3 million cases. The shortages have been exacerbated by the situation in India, the world’s largest vaccine producer, which has banned exports to deal with its own crisis.

According to Dr Phionah Atuhebwe, head of the WHO vaccine programme for Africa, the sub-Saharan region has received only 1 per cent of vaccines and 18 countries have, or are about to, run out. “It is deeply unfair,” she says.

It is not just a moral question. As Indian variant shows, we are only as safe as the least-safe country. We may feel Britain is getting the pandemic under control, but our own escape pad to normal life — if not holidays abroad — relies on others also reducing cases.

“The prioritisation of our own populations is understandable, but this pandemic isn’t going to end anywhere till it ends everywhere,” says Romilly Greenhill, the UK director of the One campaign to end extreme poverty and preventable disease by 2030. “Variants are developing where infections are high and all it takes is one variant we can’t control.” Her organisation will lobby the G7 to share one billion doses by September. This may seem a lot but as Greenhill points out, vaccine supply is set to outstrip demand in six G7 countries by the end of the summer.

The UK is one of the world’s highest per-capita buyers of vaccines, on track to have a surplus of 200 million doses. Matt Hancock, the health secretary, has argued that the British government invested heavily in vaccine development and that AstraZeneca is making its shots available at cost price. But the divide between rich and poor is set to worsen as the UK, EU, Canada and other nations sign deals for hundreds of millions more doses of Covid-19 vaccines and boosters over the next two years. Just last week, America’s National Institutes of Health began a trial giving fully vaccinated adults a booster shot of one of the three types of vaccine it has stocked.

Others are only too willing to step in. China has pledged half a billion doses of its Sinopharm vaccine to 45 countries. Russia has sent its Sputnik V vaccine everywhere from Argentina to Hungary. Neither jab has been approved by the European regulatory agency. Global health is becoming a new arena for competition between world powers, with “vaccine diplomacy” used to enhance influence and reputation.

And some countries are hard to help. Among those yet to receive vaccines are Tanzania, Burundi and Eritrea, whose leaders are Covid refuseniks.

My vaccine card is on my desk, proudly pinned next to a painting of an Afghan woman. It is a reminder that, while the scientific response has been phenomenal, the global political response is wanting. In Cornwall, in the picture-postcard setting of Carbis Bay, it is not too late to show we can be better.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout