Turn the volume down on colonial reckoning

I hope Penny Wong won’t mind my responding directly to her unsolicited advice on Britain and colonialism: before you tick us off, better sort yourself out. Mate.

In the Caribbean, they like a laugh, especially at the expense of the old colonial master: “How you mean the sun never set on the British Empire? True dat, man. God know yuh cyaan never trust a Englishman in de dark.” Australians have their own, more direct version of anti-colonial disparagement: “Where can you hide your key so a Pom can’t find it? Under the soap.”

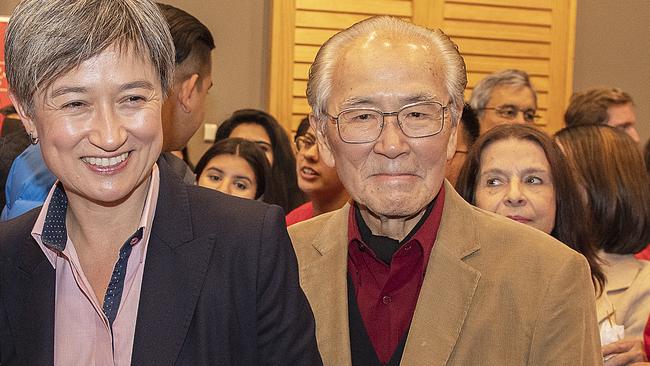

The Aussie foreign minister twisted the knife last week when she called on Britain to repent of its colonialist past. The later announcement that the King’s image would not feature on the Australian dollar emphasised that the new Labor government is in the business of leaving the colonial past behind.

Penny Wong spoke proudly of Australia’s multicultural society, touchingly evoking her own Chinese and British heritage. She then gently criticised this nation for its past. Wong may have been emboldened to have a go at us by the recent report on Britain by the UN Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent, which asserted that they had “never visited a country before where there is a culture of fear pervading black communities”.

Yet in a remarkable case of bureaucratic amnesia, the same group said of Australia just five weeks earlier: “People of African descent experience a culture of denial of racialised reality, and the legacies of this through pervasive ‘othering’ in public spaces and entrenched disadvantage.” Wong had nothing much to say about the White Australia policy introduced in 1901, when her settler ancestors were already well established in an independent Australia, and not abandoned until 1973.

According to my former colleagues in the Australian Human Rights Commission, the nation’s treatment of the oldest civilisation on Earth still haunts it. Even as Wong spoke, her prime minister was openly contemplating banning alcohol sales to quell racial unrest in the Northern Territory, where violent crime has risen 46 per cent in a year. The indigenous Australian’s life expectancy is ten years less than the average. Aboriginal people constitute 4 per cent of the total population but 27 per cent of its convicts.

I hope the plain-speaking Antipodean won’t mind my responding directly to her unsolicited advice: before you tick us off, better sort yourself out. Mate.

However, as we approach Commonwealth Day in March, and the coronation in May, we can expect more of this kind of sanctimonious finger-pointing. The early shots in what the Oxford don Nigel Biggar calls the “imperial history war” are already being fired. His new book Colonialism, which I have reviewed elsewhere, is a worthy plea for perspective. He sagely quotes the historian Margery Perham: “The attempt to judge an empire is rather like approaching an elephant with a tape measure.”

Like some others on these pages, I have lived at both ends of the imperial telescope. Freedom has always been the better choice, and no one in their right mind hankers after the past. But it came with a price tag and there must be some balance in the account.

This is not the bigoted defence that the empire civilised the darkies. The issue was one of common values overcoming local chauvinism. Left to themselves, the Canadians would have refused to enfranchise even white women. In 1929 it took the Privy Council in London to overrule the Canadians’ own supreme court for Cairine Wilson to be appointed to the Senate. It took until 1968 to elect a First Nations MP.

In much of the Commonwealth, anti-death penalty abolitionists have been dismayed by the persistence of capital punishment on the statute books of former colonies, many in the Caribbean; only the foot-dragging intervention of the Privy Council, still the last court of appeal in two dozen former colonies, has prevented more judicial execution.

But of course, most of those crossing swords in these matters don’t much care about such wrinkles. Their purpose is to damn the UK present with an uncompromisingly vicious account of the UK past. The consequence is to reduce the colonised and indigenous to mere pawns. A Guardian journalist with whom I debated these issues accused me of playing down imperial culpability, since many of the worst practices were colonial inheritances. To her, we so lacked agency we didn’t even have the capacity to be wicked without being instructed by our colonial masters.

I disagree. Nothing illustrates the persistence of intolerance better than the post-colonial fate of LGBT communities in countries like Jamaica, Uganda and Singapore, where the ascendancy of the popular will has intensified legally permitted homophobia. For example, bizarrely, it took almost a decade of legal warfare for a law against cross dressing in public to be struck down by the Caribbean Court of Justice.

But just as the decolonised can display the darker side of humanity, those who benefited from slavery can show an uncomplicated desire to even up the scales weighted by history. The BBC correspondent Laura Trevelyan announced that her family, which once owned slaves in the Caribbean, had donated pounds 100,000 to Grenada to fund development, in recognition of the compensation payments they had received at abolition.

Trevelyan, whom I knew slightly when we were young TV journalists, does not strike me as an ostentatious do-gooder. I do not know how wealthy she is, and some will grumble that relative to their compensation the donation is small. I don’t think it matters. The point is the Trevelyans have chosen not to noisily relitigate the sins of yesterday; they have offered to help create a better today. Lesson to be learnt, everyone.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout