Donald Trump’s war with Twitter could hurt social media reform

The President’s spat with Jack Dorsey’s empire could turn into a big headache for Big Tech — and might undermine reforms.

As so often with Donald Trump, it started with a tweet: “There is NO WAY (ZERO!) that Mail-In Ballots will be anything less than substantially fraudulent.”

The President was enraged last Tuesday by a plan in California, America’s biggest state, to ditch physical voting stations and shift the upcoming presidential ballot to an entirely postal operation to curb the spread of the coronavirus. Mr Trump alleged that ballots would be stolen and forged on an epic scale. “This will be a Rigged Election,” he added.

There was little evidence to back up his claims: Justin Levitt of Loyola Law School in Los Angeles analysed more than one billion votes cast between 2000 and 2014. He found 31 incidents of identity fraud.

Twitter, which for years has allowed its most famous user to rant, rave, bully and bluster uninterrupted, decided, finally, to wade in. The $US24bn ($36bn) company slapped “fact-check” links under his tweets.

The President and his allies swiftly labelled the move “censorship” — even though it was, in truth, a baby step. His tweets were not removed or edited. Instead, the President’s favoured digital bullhorn appended a link in small print encouraging readers to “get the facts” about postal voting.

The following day, Mr Trump signed an executive order telling regulators to strip legal immunity from companies found to have restricted certain voices on their platforms, specifically naming Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube.

The move threatens to kneecap the law upon which the modern web — and the empires that dominate it — are built. It sets the stage for an all-out war that experts say may actually delay long-running efforts to hold the Silicon Valley giants to account.

Daniel Gross, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur, said the order could be a “Franz Ferdinand moment” (the Austrian archduke whose assassination triggered the First World War) as social media companies go to battle with the government over the future of the internet — and their businesses. Tech trade groups are understood to be readying a federal lawsuit to strike down the order.

Hany Farid, a University of California computer science professor and a critic of the industry, said: “There is a path forward to holding the sector more accountable for the harm (caused by) their services, while encouraging an open and free exchange of ideas. This executive order is not a productive part of that path.”

The cornerstone of the web is Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act 1996. The law, passed when less than 10 per cent of America or Britain had internet access, gives blanket immunity to platforms for content posted by users. As terrorism, child sexual abuse, misinformation, propaganda and conspiracies have spread across social media, calls for greater accountability have increasingly focused on either repealing Section 230 or carving it up to so that platforms can indeed be held liable for certain content.

The industry has fought those efforts tooth and nail. Mr Trump has now put Section 230 in the line of fire. He has also exposed fault lines between the tech giants and how politically charged the issue of online expression has become just months before election.

Facebook chief Mark Zuckerberg went on conservative news channel Fox News to bash Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s chief executive, saying: “Facebook shouldn’t be the arbiter of truth of everything that people say online.” To wit, the President posted the exact same Twitter messages on Facebook. Facebook left them up.

It did the same after violent protests broke out over the death in police custody of George Floyd, an unarmed black man.

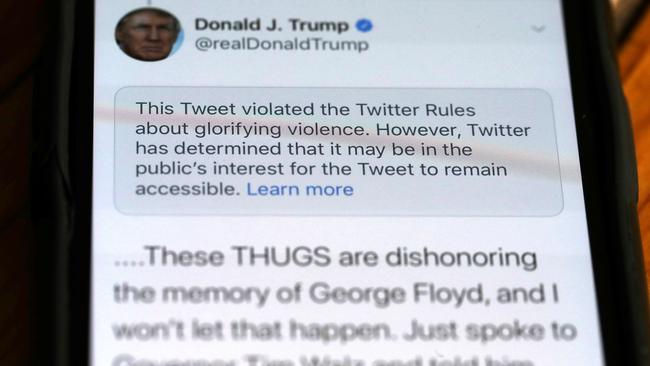

“When the looting starts, the shooting starts,” Mr Trump had tweeted. Twitter covered it with a warning about tweets that “glorify violence”, next to a button that allowed readers to view the message. Mr Zuckerberg left it up.

The Facebook chief explained: “I believe people should be able to see this for themselves, because ultimately, accountability for those in positions of power can only happen when their speech is scrutinised out in the open.”

(Mr Trump later sought to clarify the post, claiming it was a warning against violence rather than a promotion of it.)

Mr Zuckerberg’s position struck many as inconsistent. Just last month, the 36-year-old boasted of how Facebook had labelled 50 million posts “misinformation” about the coronavirus pandemic. Mr Farid said: “The hypocrisy of his statement … Two weeks ago, you’re bragging about labelling misinformation, and the moment Mr Trump pounces on Twitter, you’re like, ‘Oh yeah, we don’t do that’.”

As for the order itself, legal scholars reckon it has little chance of surviving the courts. The order empowers the Federal Communications Commission to assess whether editorial decisions are made in “good faith” or to “stifle viewpoints with which they disagree”. The definition of good faith is vague, but if the FCC does determine that a tech company has acted unfairly, it can, in effect, remove the immunity provided by Section 230 — not just for the post in question, but for all content. This, potentially, could expose the companies to lawsuits.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, a non-governmental organisation and ardent defender of Section 230, dubbed Mr Trump’s move an “error-filled reading” of the law that was, in fact, “a transparent attempt to retaliate against Twitter for its decision to curate (well, really just to fact-check) his posts”.

With or without Mr Trump’s intervention, the chipping away at Section 230 has already begun. It is a rare issue where Democrats and Republicans have found a common cause.

The first real dent in Section 230 came in 2018, when the US congress passed an act to hold platforms liable for hosting posts used for child sex trafficking. Internet purists warned itwas a slippery slope that would kill free speech, they argued. Two years on, the web still exists — and big tech is bigger than ever.

Reformers are concerned, though, that Mr Trump’s act of political theatre may undermine efforts that have been building in the background. Mr Farid said: “It’s the worst possible timing. The Department of Justice was literally days away from releasing suggestions on reforming 230.”

The EARN IT Act, which would peel back Section 230 protections related to child sexual abuse, has been gaining momentum in the US Senate.

Mr Farid added: “This in many ways derails those very thoughtful conversations because it introduces this highly partisan component — and that is never going to end well for anybody.”

On Friday, Mr Trump took to Twitter again. He wrote: “REVOKE 230!”

The Sunday Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout