Trump’s hardline stand on migration will alienate friends

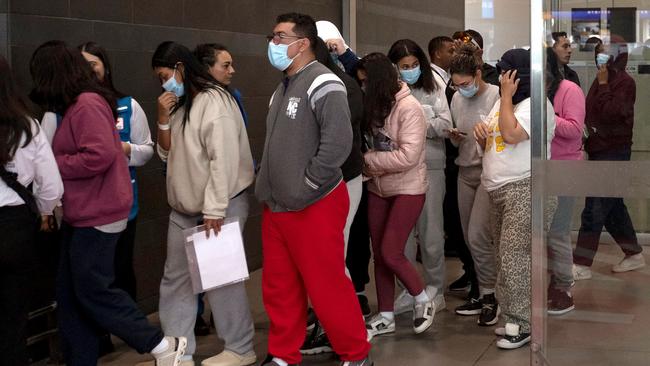

The sheer scope of the deportation campaign is designed as a frightener and as a deterrent.

One phrase stands out in the police reports from Donald Trump’s deportation round-ups of the past week. It is “collateral arrests” and applies to those migrants caught up in the raids who were often given temporary legal status under the Biden administration. They’re not illegals but now they are on a list and may soon be packing their suitcases.

The blizzard of executive orders signed so flamboyantly by the newly re-elected president has dramatically expanded the catchment area for immigration enforcement officers and shifted the language around deportation. Trump’s use of the phrase “migration crime” to legitimise a nationwide crackdown has mutated into a broader presumption of criminality. Moreover, as the armed forces are drawn into southern border defence and physical deportation, the migrant issue is turning into a national security issue. Trump talks of “aliens engaged in an invasion”.

This week’s spat between Trump and Colombian President Gustavo Petro has been presented as a domestic farce; in fact, it demonstrates how the deportation issue has set off a domino effect across the world. The left-leaning Petro briefly halted two US air force planes returning Colombian migrants to their homeland. He demanded that deported migrants be treated humanely, not transported in “shackles and chains”. A migrant, he said, “is not a criminal and must be treated with the dignity that a human being deserves”.

Trump responded with a 25 per cent tariff threat on all Colombian imports and promised to raise it to 50 per cent after seven days. Petro responded in kind, but with less impact – the US receives 26 per cent of Colombia’s foreign trade while Colombia accounts for only 1 per cent of US exports. Petro inevitably caved, though not before writing online: “You don’t like our freedom, fine. I do not shake hands with white enslavers. Overthrow me, President, and the Americas and humanity will respond.”

In fact, Latin American states, while admiring Petro’s pluck, are currently inclined to accept repatriation of their nationals rather than risk a quick escalation to an all-out trade war with their main market. That’s partly a matter of playing for time. The deportation raids are not going as swiftly as the President had hoped. In the second week of his presidency, he is demanding that immigration agencies up their quota to 1500 arrests a day of undocumented migrants.

If Trump really wants to aim for a million repatriations this year, he will have to step up that operation. Delay would leave China time to intensify trade talks in Trump’s backyard, giving Latin Americans more time to increase their bargaining clout.

The sheer scope of the deportation campaign is designed as a frightener and as a deterrent. Immigration and Customs Enforcement is now free to enter churches, schools and hospitals that could be sheltering illegals. Trump has blocked the arrival of thousands of refugees who had already been cleared for entry into the US. Schemes allowing temporary residency for Cubans, Haitians and Venezuelans are being scrubbed.

Federal officials are being directed to investigate (and perhaps prosecute) city and state authorities who interfere with deportation. Rigorous health checks will be made on all trying to cross the southern border. Birthright citizenship is to be restricted. The 101st Airborne Division is to join the military policing of the Mexican border. Other troops will speed up the construction of the border wall. The refugee program has been suspended, so has US overseas aid (for 90 days).

Trump has invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to muscle up action against foreign gangs and criminal networks.

Trump’s liberal critics say these are the seeds of a police state. I’ve lived and worked in several police states and the deportation wave does not look to me like a slide into autocracy – there will be challenges in federal courts and a demand for enormous amounts of additional funding from congress.

Abroad, there will be more Petros, more pushback from societies and states that rely on remittances from citizens living and working in prosperous countries abroad.

Trump is counting on breathtaking momentum to bewilder institutional opposition, on shock and awe.

He has one other string to his bow. His changes to immigration policy speak to the zeitgeist in a Europe witnessing the normalisation of hard-right parties in traditionally open countries such as Sweden, Germany and Austria. The Interior Minister of Austria is demanding the return of Syrian refugees now the Assad regime has been toppled. In Germany, which took the brunt of Syrian migration, the ultra-nationalist Alternative for Germany looks set to do well in general elections next month. Further afield, in Thailand, Uighur refugees are being deported to China.

The Trump deportations are being taken as the new benchmark. Once you start on mass deportations, it becomes part of a great simplifying operation, an answer to a knotty problem rather than the start of something sinister.

Trump, buoyed by his apparent success in upending US migration policy, now reckons on widespread approval for a scheme to deport Gazans to Egypt and Jordan.

For the President, it must seem as though his architecture of enforcement is something that can be exported. In fact, mass deportations can make democracies harsher, dictatorships nastier. Rather than bringing a kind of new order to the West, as Trump seems to think, the uprooting of millions is more likely to spread an even more virulent global disorder.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout