Trove of Alfred Kinsey letters reveals British carnal curiousity

Postwar letters to the academic Alfred Kinsey show wide variations in nations’ carnal curiosity.

Europeans took a romantic view. Americans were practical about the whole business. Britons, though, were fixated on the fringe theories of sex, a nation emerging from war as armchair sexologists.

An analysis of letters to Alfred Kinsey, the pioneering sexologist of the 1940s and 1950s, found that his British correspondents were often ignorant about his research but eager to share their wisdom on topics such as penis size, the effects of horoscopes on promiscuity, and gay scouts.

Ruby Ray Daily, of Northwestern University, Illinois, said that, compared with Americans and continental Europeans, the British letter-writers had a “very idiosyncratic” way of speaking about sexuality, with their eager approach typified by the Bournemouth resident who declared: “I am an amateur Sexologist.”

In her paper, in the journal Twentieth Century British History, she wrote: “The diversity of topics upon which British correspondents single-mindedly dwelled included the menstrual cycle, homosexuality in the boy scouts, the incidence of married virgins, the relationship between stuttering and repression, penis circumference, sexual jealousy, and the religious implications of conserving bodily fluids. With this context, even the most eccentric and monomaniac of letters are revealed to be typical in form if not in content.”

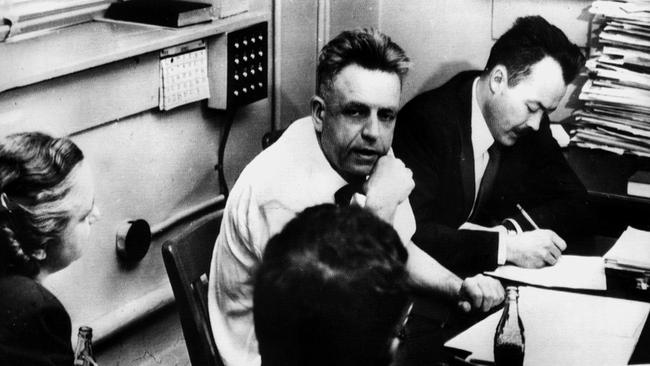

Kinsey, an entomologist turned sexologist who founded the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University in 1947, is best known for his books Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male (1948) and Sexual Behaviour in the Human Female (1953).

Rather than pronounce on what was healthy or unhealthy, ordered or disordered, the professor, who was played by Liam Neeson in the 2004 film Kinsey, was interested in documenting what people got up to and how often. He was the focus of press attention and public outrage and received letters, which are now in the archive of his institute, from around the world.

Ms Daily said that, overall, American correspondents revealed a “functional” understanding of sex that was grounded in biology. Continental Europeans were more interested in the romantic aspect and the role of sex in marriage.

One correspondent from the West Midlands, on the other hand, informed Kinsey in 1953 that sexuality was in fact governed by astrological signs. He continued: “You will now understand why I am so tremendously interested in your unique collection of data. There are astrological configurations … which correspond to frigidity and promiscuity, but the verification of such tendencies are (as you will surely appreciate) almost impossible to obtain.”

His request to view more of the professor’s data was rebuffed. Nevertheless, Kinsey, who died in 1956, sent sympathetic responses to many people.

Among the scores of letters from Britons is one from a don at Trinity College, Cambridge, who was preoccupied in 1950 with the question of whether “the educated Englishman”, who had been “segregated” at public school and university, was more likely than American men to be “initiated by older and more experienced females”.

A subject that Ms Daily said fascinated a disproportionate number of Kinsey’s British correspondents was circumcision, despite a significant decline in the practice after the founding of the National Health Service. A man from Cardiff wrote in 1954 to berate Kinsey for the dearth of information on the subject in Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male. He blamed his intact foreskin for the brief nature of his sexual encounters.

Up against unsympathetic doctors, he asked Kinsey to send him data on rates of premature ejaculation in uncircumcised versus circumcised men.

Some of Kinsey’s British correspondents wished to debate the implications or prevalence of homosexuality. In 1951 a man claiming to be a police officer sent Kinsey a series of garbled letters to inform him that all boy scouts were “homo-sexual”.

Ms Daly said that while many Britons at the time would not have had the same degree of interest in sexology as Kinsey’s correspondents, or shared their most outlandish views, the letters probably reflected ways in which people more broadly thought about it.

She added that the “evidence of widespread sexual idiosyncrasy” and a fixation on seemingly random aspects of sexuality might appear to corroborate the cliche of Britain as a repressed nation. She suggested that it was true that such thinking flourished in a “vacuum of public debate” while there was little open discussion of sex. On the other hand, she found that Britons of all backgrounds were often more graphic in their letters than other nationalities.

The Times