Health and fitness tips for over-40s from top athletes’ orthopaedic surgeon Bill Ribbans

Orthopaedic surgeon Bill Ribbans has helped to prolong the careers of many sports stars. Now he wants to help you to stay in shape

During his 40-year career Bill Ribbans has tended to many of the top names in sport. Among the walking wounded that the British orthopaedic surgeon has helped to steer back to glory are the Olympic heptathlete Jessica Ennis-Hill, marathoner Paula Radcliffe, sprinter Christine Ohuruogu, long-jumper Greg Rutherford and rugby halfback Matt Dawson have all benefited from his skills, and he has advised the British Boxing Board of Control and the England rugby union team. He has also been the orthopaedic surgeon to English National Ballet.

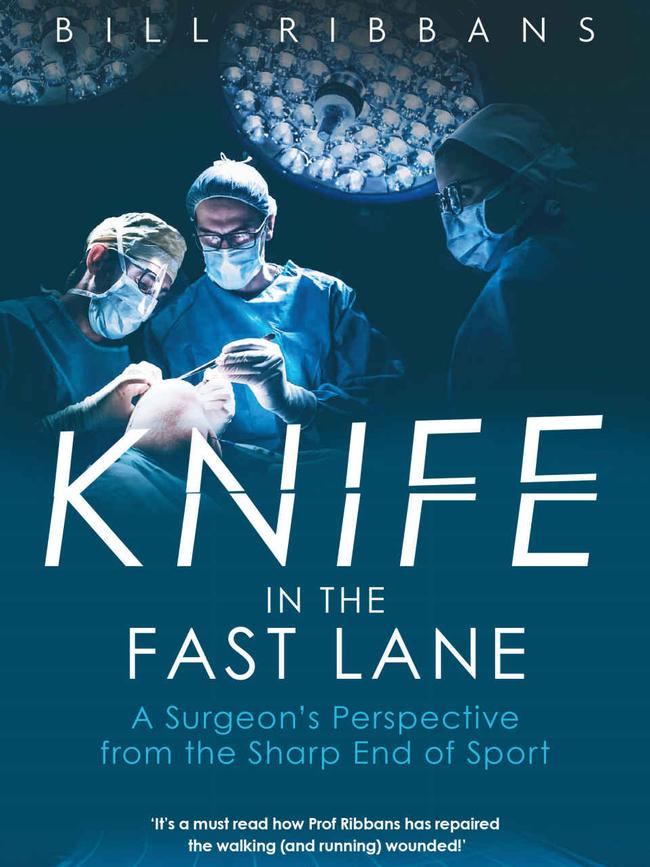

However, in his new book, Knife in the Fast Lane: A Surgeon’s Perspective from the Sharp End of Sport, Ribbans says the lessons learnt from treating them can be applied to us all.

“You don’t need to be an elite athlete to experience problems with your joints, muscles and tendons,” Ribbans says. “By the age of 50, almost all of us has an orthopaedic problem that will never go away. Knee cartilages fray and the plump, water-filled spinal discs of our youth resemble dried-up prunes.”

Exercise remains the single most important thing we can do to enhance health and self-preservation. Yet the way we work out is key and can improve — or worsen — the odds of injury or of having to go under the surgeons’ knife in our forties, fifties and beyond. “We are complicated machines with wonderful control mechanisms,” Ribbans says, “but we are still machines with built-in obsolescences and at some point we will start to break down.”

So what should and shouldn’t we be doing? Here are his golden rules for holding it all together.

Don’t run more than 1600km a year

“For me, nothing replaces the pure joy of running,” Ribbans says. “However, the high-impact nature of the activity means that, for all runners, our tendons, joints and knees are running on borrowed time. During my career I have reached the conclusion that our bodies have a finite number of miles on their clock before they inevitably start to break down. Many of us never reach these limits because we don’t do enough sport and there are huge individual variations down to genetics, injuries and how well we look after our bodies as machines.

“But generally, if you have been running or playing sport for years you will find that the Achilles tendons, in particular, start to complain. If you came to sport later in life or didn’t take up running until your thirties or forties, then these effects will be delayed. But for the average committed runner, consistently exceeding 1000 miles a year (about 30km a week) for several decades will usually lead to some joint or tendon injuries by their fifties.”

Don’t dive into running a full marathon

“Usually, the London Marathon (which normally takes place in April) and Great North Run (a half-marathon in September) loom large in my clinic diary,” he says. “So many people enter these and other endurance events without appreciating that it is not a given their bodies will cope with the required training. Several weeks before they take place I see runners with stressed bones and sausage-shaped Achilles tendons limping into my clinic, and the week after is busy with fractures to be screwed or plastered, joints to be drained and tendons to be coaxed back to normal dimensions.

“My advice is to see how your body copes with distances such as 5km and 10km before taking on the challenge of anything further. Training for distances up to a half-marathon can generally fit around work and life commitments for most people, but full marathon training is all-encompassing. It places huge demands on the muscles and joints, and not everyone is built to run that far.”

Take vitamin D

“A study of my surgical patients found just one sixth of them to have reasonable levels of vitamin D. One in five had levels so low that they were risking their bone health,” Ribbans says. “There is little doubt that without vitamin D, we risk our bones turning to jelly — and this is even true for athletes. I recently published a review of evidence on the importance of vitamin D in the BMJ’s Journal of the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine and looked at studies that showed vitamin D supplementation for all ages can both improve bone density and reduce the risk of fractures as well as improve muscle strength.

“Some researchers have shown a direct link between vitamin D levels and muscle power, force, velocity and jump height in teenagers and others — that it reduces muscle atrophy and fracture risk in the elderly. We found that long-term intake of 4000 international units (100mcg) a day is safe for most adults and children over 11 years of age, including pregnant and breastfeeding women, and reported that vitamin D2 is much less effective than D3 in achieving desired serum levels.”

Take your kids walking, running or cycling

“Twenty years ago it was rare to see a teenager with an ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) injury, a tear of one of the major ligaments in the knee,” Ribbans says. “Now they are common and we barely bat an eyelid when we see them. Rupturing the ACL in your teens is a disaster because the knee will never be the same again — surgical measures have improved a lot, but a staggeringly high rate of one quarter of children who undergo ACL reconstruction will re-injure the ligament. And their risk of osteoarthritis of the knee in later life increases several-fold.

“There are two sides to this coin. On one hand there are children who are hot-housed in the academies of professional rugby and football clubs where an obsession with producing quicker, fitter and stronger young athletes through far too intense training regimens is resulting in injuries normally associated with adult athletes being seen in adolescents. These academies fill kids’ minds with the nonsense that they are ‘elite’ at far too young an age and the chances of them getting injured are far greater than them making it in the sport.

“At the other end of the spectrum are teenagers getting ACL injuries because they are overweight and under-conditioned for regular activity. My advice to parents is to find the middle road and encourage their children to engage in a variety of sports and activities while their bodies are growing and maturing.”

Don’t bother with MRI scans

“I see so many people aged 50-plus with sore knees or hips who want to get an MRI scan to check what’s wrong,” he says. “But an MRI scan is not mandatory nor desirable for every ache and pain and, more often than not as you get older, won’t always provide the answers.

“A 2015 study showed that 43 per cent of knee MRI scans were useless, a figure that rose to 82 per cent if an amateur athlete had knee wear and tear. As surgeons we have been warned against relying on MRI scanning often in favour of the simple but effective (and far less expensive) x-ray. Even if you do have an MRI scan, it is likely to reveal age-related decline in cartilage health in most people over 50 and that doesn’t necessarily mean it is the cause of your joint pain.”

Mix up your workouts

“As we get older our body’s need for self-preservation changes,” Ribbans says. “We still need to keep our heart and lungs healthy, but emphasis should shift towards the retention of strength and balance. Cardiovascular activity such as running, cycling and swimming should be viewed as part of a balanced weekly program of exercise — in short, you need to mix it up a bit once you get past 40. Include some strength and conditioning, mobility and stretching activity, and mix weight-bearing aerobic exercise such as running with non-weight bearing activities such as swimming and cycling. Don’t overdo it. Another word of warning I give to patients is that we need some padding as we age and a BMI of under 18.5 is a fracture risk factor. By all means, keep training and exercising, but over-50s shouldn’t be too obsessed with weight and the scales.”

Factor in extra recovery time

“One of the things I struggle to convince my patients in their forties and fifties about is the beneficial effects of rest,” he says. “I’ve noticed that injuries occur when people of this age group and older who are used to doing three hard workouts a week bump it up to four. Doing that means that two of the sessions must be back-to-back and that leaves less time for recovery.

“Our bones, muscles, tendons, collagen and joints need time to assimilate the impact of exercise, more so as we age. Provided there is adequate recovery, they adapt positively to the stress of exercise, but if we batter our bodies too often the outcome can be negative.

“Collagen type 1 (a key player) response peaks three days after intense exercise, which is probably the best time to work out hard again for most people — but go back too quickly and you risk damage. The same advice applies to recuperation from injury, which takes longer as we get older.

“Nobody should expect to get back after serious injury at the same rate as a professional athlete. We used to reckon a year was needed to recover fully from an ACL injury, but improved treatments now mean it is about nine months, and there’s never a 100 per cent guarantee you will return at the same level. Rush things and neglect rehab exercises and you won’t reach full recovery potential.”

Avoid diet and fitness fads

“One of the biggest disasters for joints in terms of fitness fads was the trend for barefoot running,” he says. “It was a complete catastrophe and I’m thankful that fad has passed because it caused so many problems. Going shoeless is fine if you have done that since birth, but suddenly switching to zero cushioning and support on your feet when you are in your thirties or older and might be overweight is asking for trouble.

“Faddy diets can also cause problems. Veganism is fine if it is well planned, but it was no surprise to me that a recent study showed vegans are at a 43 per cent higher risk of fractures than meat eaters, with the risk for hip fractures in vegans more than twice that for those who ate meat.

“It is not the diet approach in itself that is harmful, but a lack of careful planning for it. Under-eating and missing out food groups is especially risky during adolescence when accumulation of bone mass can be compromised. Peak bone mass is reached by age 18 to 20 and the level then determines how strong your bones will be for life. Poor diet and exercise habits at that time mean a drastic cut in opportunities for rapid bone density to be accrued.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout