Time’s up, Joe Biden – quit while you’re still standing

The Generalisimo, captain general of the army, captain general of the air force, captain general of the navy and dictator of Spain, lisped his way agonisingly slowly through the annual pieties, in the final “Que viva Espana!” barely able to sound the consonants.

He was there, I suppose, for the sake of “continuity”. But by then figures in the shadows around him had been gradually stripping away his executive powers. Or so one hopes.

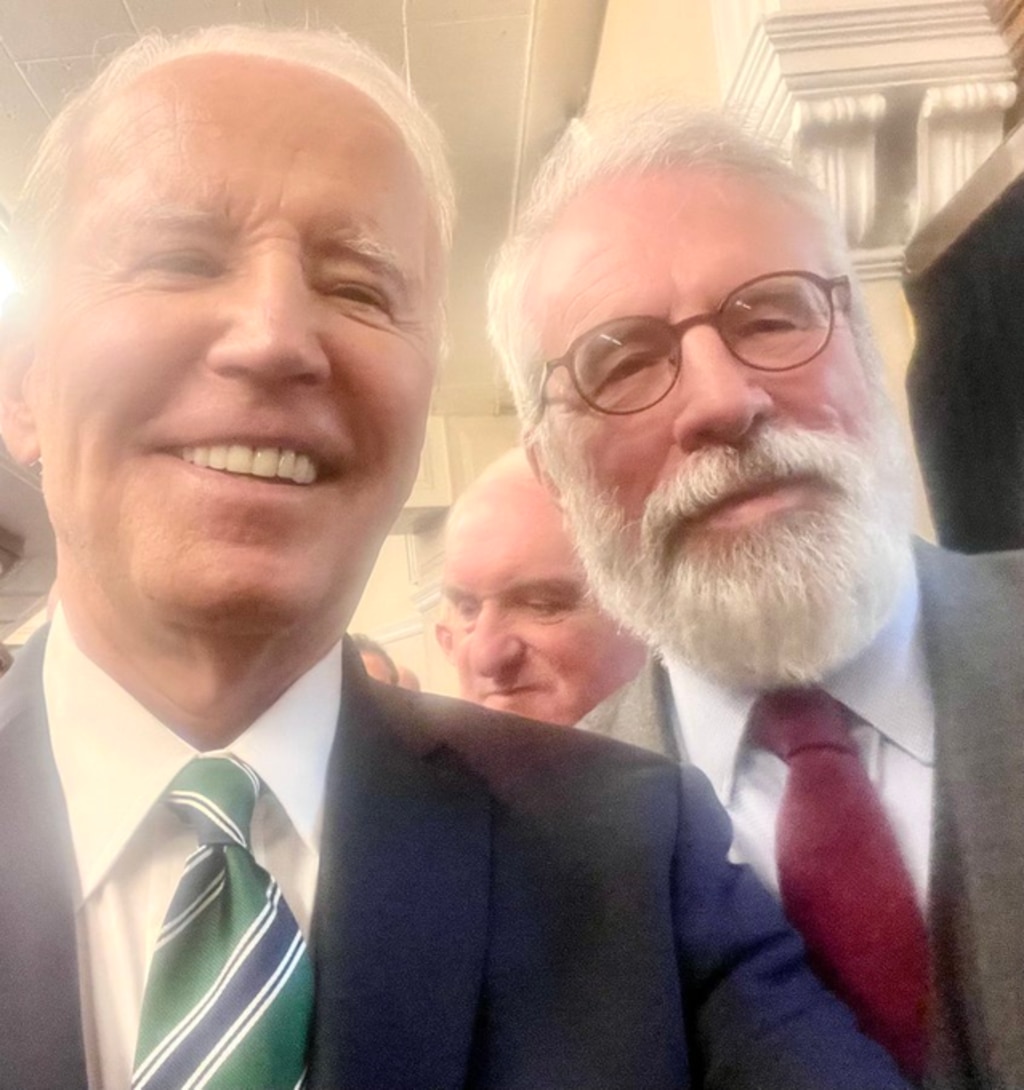

One hopes the same of US President Joe Biden who, should he stand and win next year, would be 82 by Inauguration Day. Donald Trump would be 78. Biden has so far stopped mercifully short of any public declaration that he will run, and that’s wise. He should yield gracefully to old age – and I say so while admiring his lifetime service to democratic politics and sharing his political instincts.

I’ve been watching his progress around Ireland. Likeable? Always. But he looks almost bewildered. Your eyes follow him down the stairs, willing him to hold the banister; you follow his strange, flat delivery, anxious lest he fluff his lines.

Face it, fellow respecters of the US President: this is getting embarrassing. Sometimes it’s just funny (“Rash Sunuk is now the Prime Minister”); sometimes it’s worrying (“poor kids are just as bright and talented as white kids”); and sometimes it’s cringeworthy (“America is a nation that can be defined in a single word: Awdsmfoothimaaafootafootawh ... ‘scuse me”). But the stumbles, verbal and actual, betray a growing incapacity for the highest office.

I turn 74 this year. As we pass Psalm 90’s milestone (“the days of our years are threescore years and ten”) we all, I’d guess, begin thinking about the impact of age on capacity. The question only grows more troubling as medical science extends longevity and increases the likelihood that the brain fails before the body does.

Once, nature had a way of telling us when to stop: we stopped when we dropped. Today it’s often up to us: the decision may lie in the individual’s own hands, or the hands of their employers, and for political leaders it’s often their own to take.

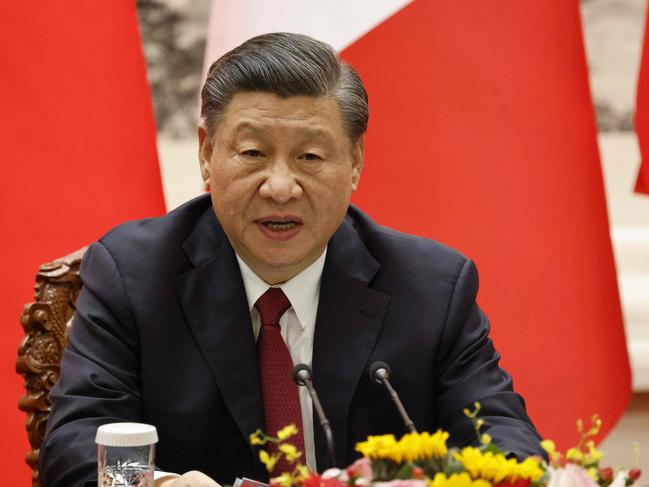

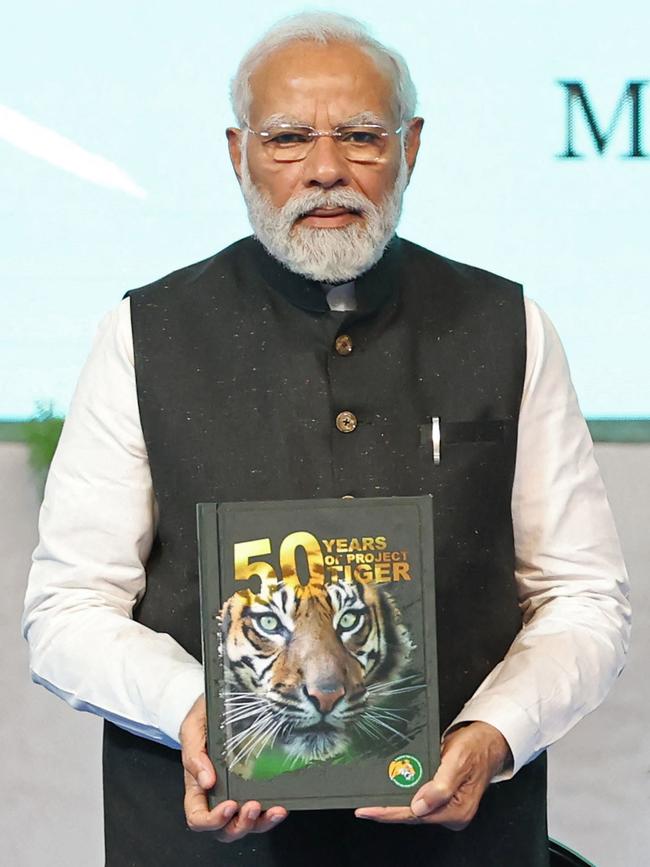

Traditionally, Africa has been the worst culprit. Robert Mugabe was 93 and Emmerson Mnangagwa is 80; Jomo Kenyatta was 84; at 80 Nelson Mandela was past it. But Vladimir Putin too is 70, and Xi Jinping turns 70 this year. Mao Zedong reached 82 in office, worse luck; while at 72 Narendra Modi shows no sign of quitting.

Meanwhile, a new king is about to ascend to our own throne – at 74. When should our leaders go? When should anyone go?

We may make, I think, three big mistakes as we search for the answer. First, we try to be categorical: we look for a formula. But humans age mentally (and physically) at wildly different rates. Some are pretty sharp at 90; others are beginning to lose it at 70.

Second, we often speak as though someone’s absolutely OK until they aren’t. But except in the case of Alzheimer’s or clinical dementia, there’s no cliff edge: more likely a steepening slope. From youth we all deteriorate mentally and physically but there isn’t a turning point and there are no milestones. “She’s still all there” would usually be better rendered “she’s still mostly there”. And when it’s obviously time for someone to stop they’ve often passed the point when they realise it.

Third, we go on rather too much about wisdom, experience and judgment. We oldies not unnaturally place a high value on acquired knowledge because that’s what we do have; and a lower value on the capacity to acquire it because that’s what we’re losing. I don’t disparage the getting of wisdom and experience, but point out that there will always be a tipping point at which the undoubted value of what life has taught us begins to be outweighed by our diminishing ability to learn, to respond, to react and to improve our performance.

Where that mental tipping point is placed will vary depending on the job. In computer programming it probably comes at about 22. For a professional marathon runner (where mental fortitude counts) it could be the thirties. For a primary school teacher, the fifties. For the average chief executive, chief constable or GP it may come in his or her sixties.

University professors, local councillors, archbishops, judges and backbench MPs may carry on usefully into their seventies.

For the chairman of the board, the owner of an antiquarian bookshop, the art dealer, the landscape artist, the porcelain collector or the King, there may be no limit if the spirit is willing and the brain still in gear. In all these pursuits, acquired knowledge and long experience are so valuable as to outweigh a loss of mental speed and agility.

But even here there’s a caveat I’d point to. In George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda the Princess says to Daniel: “You speak, as men do, as if you felt yourself wise.” There is a downside to wisdom – or, rather, to the belief that one is wise. I do best here, perhaps, to refer to the person I know best, and speak from my own experience.

There’s a tendency as we get older to allow a weariness to settle on us, and it can be fatal in politicians. We’ve “seen it all before”, we mutter. “That’s been tried already/ If that was the answer someone would have done it years ago/ Not so fast, young man.” The world as it is seems ever more compelling, the world as it could be, ever less plausible. The unlikelihood that anything new will work, when nothing has yet, weighs heavily. I recall the smug satisfaction with which I WhatsApped an old ditty to Michael Gove on his becoming secretary of state for levelling up: “They said it couldn’t be done/ They said you can never do it/So he took that job that couldn’t be done/ And he couldn’t do it.” What a dreadful piece of advice.

In a president, a prime minister, a party secretary or a dictator, two things, needful in these roles, are likely to be lost as the years pile high and the arteries of the imagination harden. First, the mental aptitude for absorbing, grasping, responding fast and taking snap decisions. Second, the more philosophical capacity to consider whether one might be completely wrong, and that there might be new things under the sun.

Time to step back Jinping, Donald, Emmerson, Narendra (and, one day, no doubt, your columnist). Joe, by 2024 history may file you under “mildly successful presidents”. There are worse categories. Quit!

The Times

More Coverage

My father’s job took our family to Spain in 1973. General Francisco Franco was 79. Every year he gave a new year’s address to the nation. I remember a shrunken figure, heavy with medals, his neck in folds of skin gathered into his collar, sitting upright as if only an aide’s hidden arm up his jacket kept his back straight.