Time to put the history men back on their pedestals

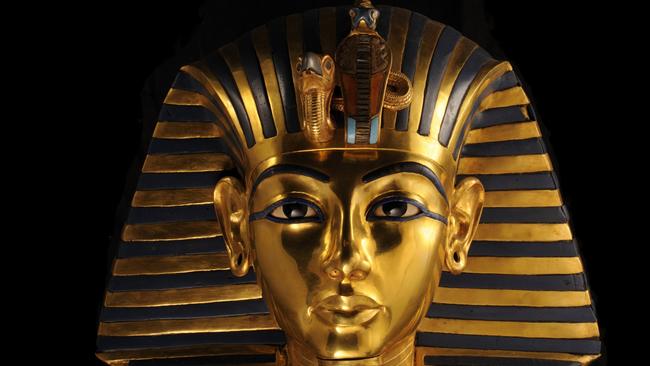

Tut is eternally famous. To be face-to-face in Cairo with that golden mask is something I will never forget. I take an odd associative pride in the fact that The Times bought exclusive access to the discovery, and even that the Daily Mail’s thwarted correspondent may have invented the story of the curse of Tutankhamun as a form of petty revenge.

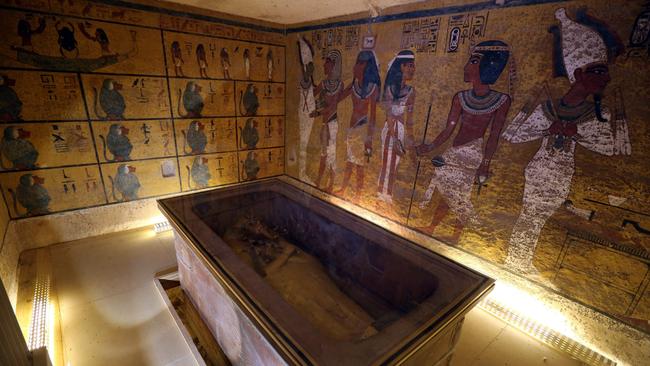

Two days earlier and 1,000 miles to the east, Leonard Woolley and his team began their first excavation at the site of the ancient city of Ur in Iraq. By the end of the decade his discoveries were as famous as those by Carter in the Valley of the Kings. They are less celebrated now, but Woolley’s work was far more significant in advancing our knowledge of the lost world than was the pharaoh’s tomb. What he uncovered gave us the deepest insights into how the first cities developed and how the earliest complex societies were governed.

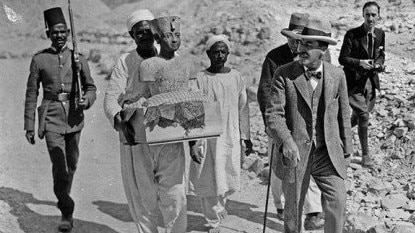

Woolley was no rapacious Indiana Jones dig-and-take-away merchant, but one of the first scientific archaeologists, surveying sites meticulously, excavating carefully, noting, for example, that where objects had been held together with wood that had since perished, a gap was often left from which his team could make a cast. He left 20,000 pages of notes and took thousands of photographs. Some of the objects he discovered, like an arrowhead now in the British Museum, belonged to a pre-urban culture 6,000-8,000 years old. His work uncovered houses and communal buildings from a range of periods, as well as temples and a huge ziggurat. And among the objects he discovered were thousands of clay tablets covered in cuneiform writing.

It was revelations in what came to be called the royal cemetery that most immediately appealed to the interwar press and public. Some tombs contained the bodies of several dozen people who appeared to have been sacrificed as their master or mistress was interred. In others, wonderful objects were found: golden headdresses, sculptures and the so-called “royal standard of Ur”, a box decorated with lapis lazuli and red limestone, depicting scenes of city life and showing the king at home and at war.

In 1934, with the money running out, Woolley closed down his operation. By agreement, half the material and records represented the first acquisitions by the National Museum of Iraq. The other half was divided equally between the sponsoring institutions: Penn Museum in Philadelphia and the British Museum. The artefacts held in London are easily retrievable on the museum’s website. Many are unspectacular to look at, but together create for scholars a detailed picture of that early world. Others, like the royal standard and the “ram caught in a thicket” sculpture, made from gold, copper and lapis lazuli, are astonishing.

The story of what happened to the objects in the Baghdad museum is both sadder and, in its own way, optimistic. Sadder because in the chaos following the allied invasion in 2003, looters took whatever they could. Optimistic because of the international effort to find and return thousands of objects. Once again, slowly, visitors are returning to see where the ancient cities stood and visit the museum.

Perhaps partly because of this recent history, the achievements of men and women such as Woolley and his archaeologist wife, Katharine, are these days, I feel, denigrated as the work of colonialists and despoilers, when they were anything but. And by association the institutions that funded them and displayed some of their objects and archived many more are regarded as instruments of empire rather than of learning and scholarship.

We concentrate on the objects and engage increasingly in public debates about moral ownership, overlooking the role of these institutions in research, preservation and discovery. But the curators and staff of our galleries are far more than the custodians of objects. They are usually deeply expert in their fields. Someone such as Dr Irving Finkel, the British Museum’s assistant keeper of ancient Mesopotamian script, languages and cultures, who visited the museum aged nine and decided it was where he wanted to work. Finkel discovered on an ancient cuneiform tablet the rules for the world’s oldest board game, five versions of which had been found by Woolley at Ur.

But we often take this learning and hard work for granted. Earlier this week we told how an outfit in Oxford had created an “exact” replica of a Greek marble horse’s head displayed in the British Museum. They had done this after taking digital images in the museum without permission. And now their founder, Roger Michel, was suggesting, in effect, that the museum could keep the replica and send the original to Greece. “There is a low tolerance now for cultural appropriation,” said Michel, “and the British Museum is behind the times. And besides, these things were like amazing grapes for the British; they have squeezed all the wine and got as much Greek culture infused in British culture as it can hold.”

Quite apart from his misuse of the fashionable term “cultural appropriation” and the gnomic reference to wine, I felt Michel displayed too easy a contempt for the institution, based partly on ignorance of its work. And he’s far from alone.

This half term families, students, tourists and pensioners queued round the block to enter the British Museum. Which they did for free. Among them may have been a nine-year-old who would be inspired for life by the visit. Others perhaps were dragged along, sullenly, in the wake of despairing parents.

Was it just my imagination to see in the latter something of the Just Stop Oil protesters hurling their soup over a painting in the National Gallery? “What is worth more, art or life?” demanded one protester, presenting a false dichotomy that a pre-resignation government minister would be proud of. For her, despite her education, the institution and what it did seemed to hold no real value. Just another stuffy place that Mum and Dad had taken her on a wet weekend.

My object in this week of Tut and Ur is to make a plea for us to rediscover our wonder and love of learning about the past and the present even as we find new and better ways of communicating it.

The Times

A hundred years ago this week British archaeologists began two of the most extraordinary endeavours in uncovering the deep past. On November 4, 1922, Howard Carter’s team, in their last season before giving up their quest for the tomb of the pharaoh Tutankhamun, almost accidentally uncovered a stone step leading down to a sealed entrance. The rest you know.