Tickets, venues, bands, bouncers, food: Live Nation controls them all

The Oasis ticketing scandal has shone a light on the behemoth that dominates the live music industry.

When Chappell Roan, the new American pop sensation behind the hit song Pink Pony Club, walks out on stage next Sunday night, she will be greeted by more than 2,000 of her fans in Scotland.

The chances are that most of them will never have heard of a large company called Live Nation Entertainment. But each of them will have contributed to the American giant’s billions of dollars of revenues this year in ways they will not have dreamed.

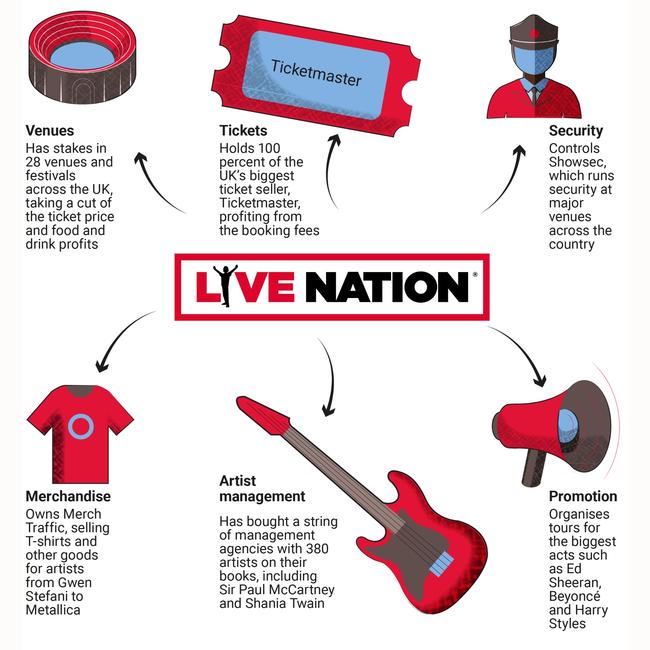

Live Nation owns a large stake in the venue, the O2 Academy Glasgow, meaning it takes a slice of the profit on every hot dog and pint of lager consumed. It owns the security company that provides the bouncers on the door and inside the venue. It is also the owner of Ticketmaster, the website through which the majority of Roan’s fans will have bought tickets to the show.

Not only that, but Live Nation has close connections with SJM, the promotions company that has organised Roan’s The Midwest Princess Tour, which works with her manager to book the venues, liaise with the ticketing agency and handle the publicity.

In other words, every part of the live music food chain appears to be dominated by the Live Nation leviathan.

Last week, Ticketmaster found itself at the heart of a scandal after its “dynamic pricing” tool, known as Platinum, was used to increase prices for next year’s shows by Oasis as an estimated ten million fans competed for about one million tickets. Prices for a pounds 148 ticket increased to as much as pounds 355.

Ticketmaster introduced this system in part to combat scalping, or secondary ticket sales, by reducing the profit margins available to resellers. But Platinum has struck a political nerve in the UK. Sir Keir Starmer pledged to get a “grip” on the industry. The Competition & Markets Authority launched an investigation. And Oasis distanced itself from “dynamic pricing”.

But while the focus has primarily been on Ticketmaster, the debacle threatens to shine a light on the scale of Live Nation’s hold over the British music industry at a time when it faces a “monopoly” lawsuit in America.

Research by The Sunday Times has found that Live Nation counts 85 companies across the UK and Ireland as its subsidiaries, either through full ownership or through shareholdings.

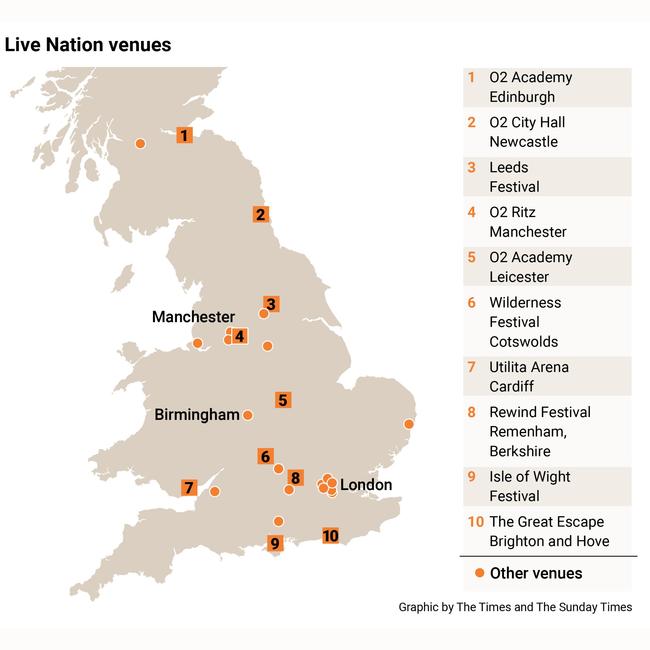

Among its UK investments and holdings are at least 28 venues and festivals. These include all O2 Academy-branded sites, which are found in most major cities. Live Nation co-owns the festival promoter Festival Republic, which runs Reading and Leeds, as well as Wireless, Latitude and the Great Escape. And it holds further investments in the Isle of Wight Festival and Boomtown.

Also among its subsidiaries are two of the three promoters working on Oasis’s reunion tour, MCD Promotions and DF Concerts. Its artist management groups include Quest, a UK-based firm that represents Sir Paul McCartney and Shania Twain, while US-based Roc Nation works with British artists Corinne Bailey Rae and Jess Glynne, and US stars such as Rihanna and Jay-Z. Live Nation even owns a string of merchandising firms.

In 2022, Live Nation’s UK concert promotions arm was part of more than 2,500 shows, which attracted 5.9 million attendees. Its revenues totalled pounds 312 million, equal to pounds 53 per admission, up from pounds 39 in 2013. These figures do not include Ticketmaster UK, which reported revenues of pounds 127 million in 2022.

By comparison, Live Nation’s promotions rival AEG Presents, which owns London’s O2 Arena, was involved in 1,071 shows in 2022, according to its UK accounts, which sold 1.7 million tickets. It reported revenues of pounds 224 million. Its ticketing platform, AXS, made revenues of pounds 22 million.

When a concertgoer buys a ticket, its face value is split between the artist, their manager and the promotion company, which may take about 10 per cent of the total for a big show, or more when lesser-known musicians are playing. The added fees, which can be about 25 per cent of the face value, are split mainly between the venue and the ticket issuer.

The result is that, on a pounds 100 ticket, a Live Nation promotion business may take pounds 10, leaving the rest to be split between artist and management, which may also include Live Nation. The salesman, often Ticketmaster, will then take around a third of a pounds 25 booking fee, with the rest going to the venue, which could also be part of the Live Nation group.

Most artists and managers declined to speak about Live Nation’s market dominance when contacted by The Sunday Times. One industry insider warned that artists would not speak for fear of losing gigs and festival appearances. “Everyone is running scared of them,” he said.

However, smaller bands were happier to talk, albeit on the condition of anonymity. The lead singer of one Liverpool-based group said: “I think Ticketmaster and Live Nation are an absolute outrage in the way they feel they can charge whatever they want for tickets, especially as musicians don’t get a fair cut. It’s total greed and a total lack of empathy, especially for up-and-coming artists.

“We’ve made a conscious decision to steer clear, but I’m sure at some point we’ll have to deal with them.”

Reg Walker, owner of The Iridium Consultancy, which specialises in ticketing, said: “Live Nation has almost a monopoly. What it doesn’t own outright, it has a minority stake in. It’s an incredible business but I think there’s a time when that business can get too big, to the point where it suffocates any potential competition. And you need competition to ensure that the prices are competitive.”

The dollars 21 billion-valued corporate giant now known as Live Nation Entertainment can trace its roots back to Arizona in 1975 when a group of friends - among them a box-office ticket seller, Albert Leffler, and a computer programmer, Peter Gadwa - founded Ticketmaster, a company that sold hardware for ticketing systems.

In 1993, the company was acquired by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, a sports and music fan who spotted the potential for it to grow as the internet spread across US households. Ticketmaster’s website launched two years later, promising to make ticket-buying more convenient for fans who could now avoid phone orders and box-office queues.

Around the same time, Robert Sillerman, the New York-born radio and media entrepreneur, started acquiring concert promotion businesses, creating a growing empire, which he called SFX. Sillerman sold the business to the US media giant Clear Channel for dollars 4.4 billion in 2000, only for its new owner to split it off as a new company - Live Nation.

By 2009, they were both the dominant players in their fields. The companies, both by then listed entities in the US, agreed a marriage that would create a giant of the music world.

The deal faced vocal opposition - Bruce Springsteen warned that it would create a “near monopoly” and “make the current ticket situation event worse for the fan” - but it was eventually waved through by competition watchdogs.

Globally, Live Nation generated revenues of dollars 23 billion (pounds 17.5 billion) last year from the sector. While Ticketmaster is a profitable business for the company, it made the bulk of its turnover from its concerts division. Last year it promoted 50,000 shows for 6,800 touring artists.

Management companies owned by Live Nation, meanwhile, have more than 380 artists on their books.

The company’s chief executive, Michael Rapino, who is married to the Star Trek: Enterprise actress Jolene Blalock, stands as one of America’s best-paid bosses. In 2022 alone, he took home dollars 139 million, a payment that included a performance-related bonus of dollars 117 million in Live Nation shares. Not bad for a man who started his career as a sales rep for Labatt Breweries, promoting bands at bars in Ontario on the side.

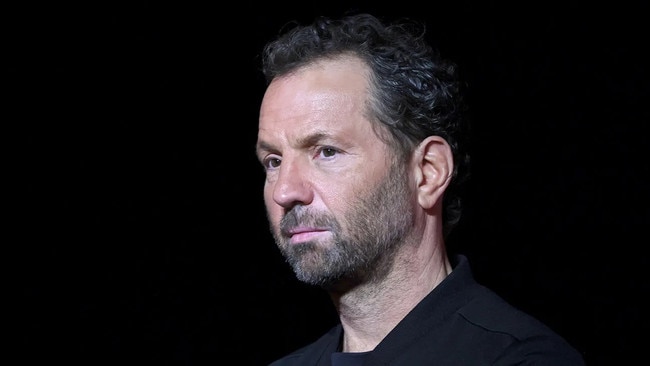

Live Nation’s president and chief financial officer, Joe Berchtold, made dollars 52 million in 2022, again thanks to a large stock payment, and more than dollars 6 million last year. The seemingly endless increases in ticket prices will not have troubled Berchtold; his pay package last year included dollars 78,315 to cover tickets to Live Nation shows and other sporting industry events for friends and family.

Today, Live Nation Entertainment faces the prospect of being broken up by the US government. In May, the Department of Justice filed a lawsuit that described the company as a “monopoly” that “thwarts competition in markets across the live entertainment industry” to the detriment of fans, artists and venues.

Clearly, such a potentially damaging lawsuit is top of the agenda for Live Nation’s management today. But there are signs that the Oasis outcry on this side of the Atlantic is causing alarm back at the executive suites in the US.

Speaking to investors at a Bank of America conference last week, Berchtold admitted that Ticketmaster now needs to offer fans “better communication” and “better transparency”.

Asked about the justice department’s lawsuit, which Live Nation is fighting, Berchtold said he expected the company to “prevail”, adding: “I don’t expect we’re going to have major changes to how we operate.” On Live Nation’s UK business, a spokesperson said: “The UK is among the most competitive markets in the world when it comes to promotions, venues and ticketing.”

Even if Ticketmaster is not to blame, the Platinum ticketing fiasco will live long in the memory of many fans.

Abi White, 27, a social media manager from Manchester, makes videos on TikTok on how to get tickets for gigs under @abisguidetogigs, but missed out on Oasis herself. She said: “I finally got into the actual website after five hours and put tickets in my basket, but then saw they were now pounds 350 each. I was like, no, wait, this isn’t right.”

Echoing the nostalgia of many others last week, she added: “I’d rather physically queue up so you could see if you had a chance of getting the tickets, and where the internet won’t boot you off.”

The Times