Three funerals to reshape the Middle East

As the chest-beating crowds swelled to more than seven million, the regime decided to delay the burial and instead of parading the coffin through the streets helicoptered the body to the Paradise of Zahra cemetery in the south of the city. At one point, the body rolled out of the coffin while mourners in search of relics tore off bits of his shroud.

Little wonder there is nervousness about another death foretold: that of Ali Khamenei, the successor to Khomeini as supreme leader. Khamenei is 85 and is said to have received cancer treatment. If he dies in the coming year, his funeral could be one of three that change the face of the Middle East. It may be morbid to consider change brought on by natural causes at a time when much of the region seems to have been ankle-deep in blood from wars that, once started, never seem to stop: Gaza, Lebanon, Syria. Yet even under the most repressive regimes you come across young people who crave a break from the past, an overhaul of society that does not completely abandon tradition.

Their frustration is with the old and out-of-touch, with the corruption of power structures that sets in after decades of only token change. So it is not only the supreme leader of Iran whose wisdom is being questioned – the whole idea of a necklace of proxy armies sheltering Iran from future attack has fallen apart under his watch – it is also King Salman of Saudi Arabia, now 88, and in the Palestinian territories, Mahmoud Abbas, who is 89.

All of them are running out of breath. All three block the road to modernisation. Everything happening around them at the moment is in response to their growing incapacitation and reflects the lack of orderly succession.

Naturally, the funeral-to-be in Iran is unlikely to be as crazed as the one in 1989. For one thing, its planning will be partly in the hands of Khamenei’s favourite son and right-hand man, Mojtaba. He has close connections with Revolutionary Guard commanders and played an important part in organising the thuggish Basij militias that crushed the 2009 attempt at a popular uprising. He will play a key part initially in any succession crisis after his father goes.

There may be more to it than a policeman’s steadying hand. Mojtaba Khamenei is a senior academic in the Qom seminary but he is not yet an ayatollah with a proven depth in theological learning; it is an open question, therefore, whether the Assembly of Experts will select him as supreme leader. The choice will be framed around who can preserve Iran as a theocratic state. It will be up to Mojtaba to persuade the elite that Iran is facing an existential crisis that has to be deftly managed if the country is to stay true to its ambitions of being the central and guiding Shia power.

If Mojtaba wins the argument, his counterpart in Saudi Arabia will be Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who has been given (or has taken) unprecedented powers. Increasingly he acts as if he is a regent. His father seems to have accepted him as the driving force in the defence of the realm and in a social transformation giving young people a greater stake in the future of the kingdom. It is, therefore, already up to Mohammed how far the Saudis should move towards containing Iran – with Israel, inside the Abraham Accords, or independently inside an enhanced special relationship with the Trump administration?

The final call on Israel still depends on the king, who insists on Palestinian independent statehood. The final call on Iran is up to the crown prince – it is for him to judge whether a new Iranian supreme leader poses an imminent threat or whether some tentative coexistence is possible. A possible nuclear arms race between Iran and Saudi Arabia will be decided only after two funerals.

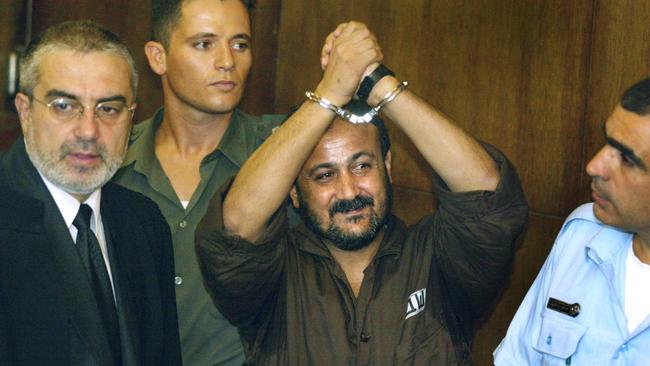

The third politically important interment is likely to be that of Abbas, head of the Palestinian Authority, chairman of Fatah, in power since 2005, a corrupt, manipulating election-resister who still, despite his advanced age, wants a role in governing postwar Gaza. Unlike Saudi Arabia, where a succession process is in place – though Prince Mohammed might have to fight off rivals – and Iran, the supposed Palestinian leader seems to believe he can rule for ever. One possible successor stands out: Marwan Barghouti, 65, who has spent the last 22 years in an Israeli jail for five murders. He has stayed defiant, leading Palestinian prisoners in a hunger strike, but has learnt Hebrew and his supporters say he would ensure less corrupt governance and keep Hamas at bay. Can the Saudis do business with him?

This is not only about shuffling intransigent old men out of the door. Younger leaders also often fail to understand conflicts. President Assad of Syria is still only 59 and has for almost a quarter of a century made life hideously worse for his subjects. Perhaps his enforced retirement could contribute to the benign reinvention of the Middle East in the year of three funerals.

The Times

The funeral of the founder of the Iranian revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, was more farce than tragedy but it firmly established the Tehran regime’s fear of crowds. It was in June 1989, a time when communist regimes from central Europe to China were trembling in their boots. In northern Tehran more than a million had gathered to pay tribute to the 89-year-old ayatollah, wrapped in a white shroud and placed in an airconditioned glass box. There were stampedes of crazed mourners.