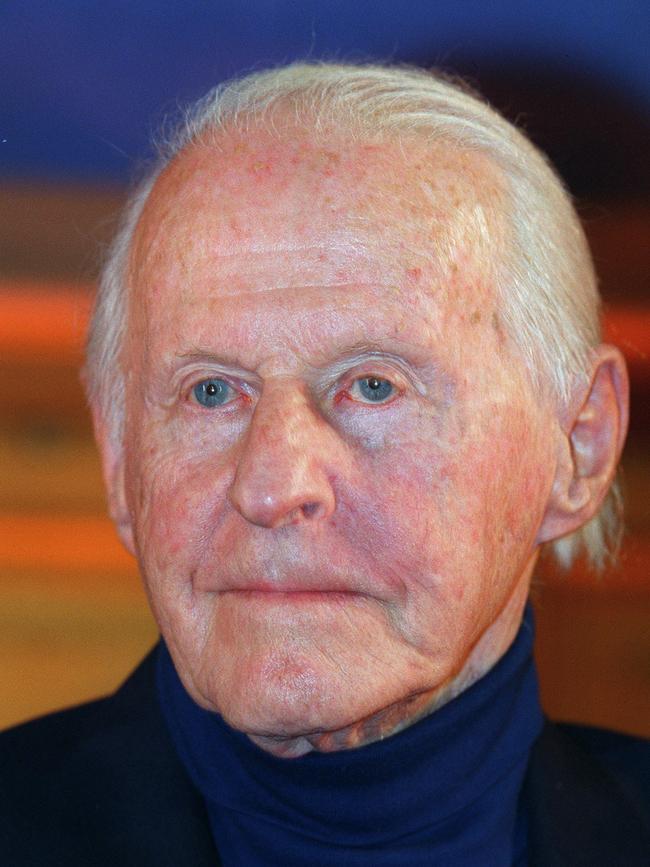

Thor Heyerdhal’s remarkable 1947 voyage on the Kon-Tiki left theory on rocks

Thor Heyerdahl was a man of imagination and courage – he was the kind of person who makes most of us feel utterly inadequate.

On August 7, 1947, beneath the vast expanse of a southern sky, one of the most daring voyages in human history came to an end. For the previous 100 days and nights Thor Heyerdahl and five crewmates had sailed west on their flimsy balsawood raft, the Kon-Tiki, carried by the winds and the waves across the sparkling blue emptiness of the Pacific. But now, on the 101st day, their journey was over.

As the current swept them towards the Raroia atoll, part of French Polynesia, Heyerdahl realised there was no escape. Some 600m from shore, he wrote afterwards, the raft struck a “low, half submerged mass of coral”. Then he felt it lift and more vast breakers tossed them on to the rocks – once, twice, three times. With every blow the wood was splintering. The mast went first; then the steering oar; then the cross-logs from the stern and the bow. Desperately Heyerdahl and his men clung to the remaining logs.

Then, at last, they saw their chance and hurled themselves out on to a nearby outcrop of jagged coral, not far from the atoll. Their raft was wrecked but they were able to salvage their food and water supplies, as well as an improvised radio. Above all, they were alive.

So ended the voyage of the Kon-Tiki, Heyerdahl’s bid to prove humans could have sailed some 7000km from Peru to Polynesia without the aid of modern technology. This, he hoped, would provide the missing link between the civilisation of the Incas and the islanders of the South Seas, overturning everything academics had believed about the prehistory of the Pacific.

Scholars have long argued about the Norwegian adventurer’s thesis. But as was reported last week, the story has taken a new twist. The latest scientific analysis suggests there must indeed have been a pre-Columbian link between Polynesia and South America, since the preserved bodies of 15 Easter Islanders in the National Museum of Natural History in Paris show traces of Native American DNA.

Was Heyerdahl right, then? Alas, the answer is almost certainly no. Though sailors almost certainly crossed the Pacific as early as the 13th century, long before the first Europeans arrived in the area, they weren’t South Americans sailing west. Instead, the overwhelming majority of scholars believe they were Polynesian islanders sailing east – something Heyerdahl, with a very Nordic sense of superiority, had believed impossible.

So does this diminish Heyerdahl’s achievement? Surely not. In the mid-20th century his attitudes were hardly unusual. And although the Kon-Tiki expedition is much less well known now than in his heyday, it should be remembered as one of the great feats of exploration and adventure.

Heyerdahl was a remarkable character. Born in the obscure Norwegian town of Larvik in 1914, he was a lonely, miserable boy who dreamed of escape. Obsessed with the South Seas, he left for the Marquesas Islands of French Polynesia, where he became fascinated by the mystery of the inhabitants’ origins.

Before Heyerdahl could test his theory that the Polynesians had come from South America, Norway was invaded by Nazi Germany. He served with distinction in the Free Norwegian Forces holding out in Finnmark on the very northern tip of Norway; then he went back to the Pacific, searching for evidence.

In the Galapagos Islands he found pottery shards that proved human beings had been there before the arrival of the first Europeans. (Or so he thought. Most modern scholars remain sceptical.) Then he went to Easter Island, where the sight of the vast stone figures quickened his appetite for adventure.

At last, in the spring of 1947, Heyerdahl was ready to put his thesis to the test. Armed with charitable donations and equipment loaned by the US Army, he built an indigenous-style raft from Peruvian balsa logs, as depicted in illustrations by the Spanish conquistadors. And on the afternoon of April 28 he and his five recruits set off from Callao, Peru, determined to reach the atolls of Polynesia.

Some readers, I fear, may be tempted to scoff at Heyerdahl’s boyish enthusiasm. He was a throwback, an enthusiastic amateur in an increasingly professional age. Even at the time, most academic scholars thought his thesis was plain wrong.

And today his belief that Polynesia must have been settled by blond, blue-eyed, white-skinned sailors from South America, whose ancestors had travelled from ancient Mesopotamia, sounds like the ranting of a YouTuber with some very alarming political opinions.

Indeed, if you were being really critical you might dismiss Heyerdahl as an early example of the sensation-seeking pseudo-historian, not unlike Netflix’s darling, Graham Hancock. For the Kon-Tiki wasn’t his only venture into the wilds of prehistory, and his eagerness to make implausible connections didn’t stop at the Pacific.

He also built a papyrus boat, the Ra, to prove the ancient Egyptians might have crossed the Atlantic; and a reed boat, Tigris, to show the Mesopotamians might have visited India. On top of that, he also claimed that Viking civilisation might have originated in Azerbaijan, and suggested that gods such as Odin and Thor had once lived near Baku, its capital.

But there was more than one difference between Heyerdahl and the crackpot theorists who have followed in his wake. He wasn’t just an attention-seeker; he thirsted for knowledge, was a keen supporter of academic archaeology, and was genuinely admired by most experts, even as they disagreed with him.

Above all, he was the very opposite of an armchair theorist. How many of us would dare to take the balsawood Kon-Tiki across the Pacific for more than 7000km? Who among us would then set out across the Atlantic in a boat made of papyrus, sailing for another 7000km while water lapped over the sides?

Heyerdahl wasn’t just a man of imagination; he was a man of courage. In other words, he was the kind of person who makes most of us feel utterly inadequate. And yes, he was almost certainly completely wrong. But who among us is always right?

The Times