The trauma of Trump – can we still do business with his America?

Yet it seems wiser to assume, as Ukrainians and most of Europe do, that Trump and his acolytes mean what they say: that he regards Ukraine as being rightfully a Russian vassal state and its current leader as bereft of legitimacy; that the defence of Europe is no longer an American priority; that he is happy to embrace Russia’s Vladimir Putin; and that he will subject America’s traditional European allies to a continuing barrage of insults.

Think how far we have come, or descended, since June 26, 1963, when John F Kennedy, before a vast crowd in a West Berlin beleaguered by the Soviet Union, delivered one of the greatest speeches of the Cold War, which included the famous words “Ich bin ein Berliner!” The president’s personal identification with the plight of those in the front line of the nuclear confrontation between east and west prompted tumultuous applause from its audience and inspired the free world.

By contrast, this week Trump declared that President Zelensky is the dictator of a nation that has been riding a gravy train funded by the United States, and that the war that started in 2022 with Putin’s invasion is the fault of Ukraine for seeking to embrace the West.

The US president’s remarks – repeated several times since Monday – have left European leaders reeling, audibly bemused about how to respond. After a decade questing for a strategy for managing an aggressive Russia, suddenly the challenge has become that of how to live with a new kind of US – the friend and not the foe of dictators; its leaders standard-bearers for mendacity, who have thrown away the traditional courtesies and conventions of diplomacy.

The crises that such a world view could precipitate go far beyond the immediate one of Ukraine. If Trump fulfils his threat to cut Europe loose, there is little prospect that the Europeans, including the British, would stand beside America in a future armed confrontation with China.

This throws into doubt the AUKUS pact, founded on a three-nation commitment to build and deploy nuclear submarines in the Pacific. The treaty has become a key pillar of Britain’s defence policy, not to mention Australia’s.

Moreover, it is hard to see a credible role for Britain’s two aircraft-carriers if the Royal Navy is not operating in tandem with the US navy, and if we are struggling to contain the Russian menace in home waters without American might.

It seems foolish to pretend we can do business as usual with such an America as Trump seems bent upon creating. But it is equally absurd to suppose that we can turn our backs upon it. We cannot send the president to stand in the corner. Instead we must focus on practicalities – how to live with this new reality through the next four years and how best to preserve Ukraine from being thrown to Putin’s wolves.

By chance, I have just been rereading that 1952 masterpiece The Struggle for Europe, an account of WWII and its aftermath written by the Australian former war correspondent Chester Wilmot.

Wilmot wrote fiercely about strength as the only commodity that impressed the leaders of the Soviet Union, “relentless in pursuit of what they believe to be Soviet interests … Concessions made as gestures of goodwill were invariably interpreted as evidence of weakness and served only to encourage them to drive a harder bargain.”

Wilmot was merciless in his criticisms of the Americans for their naivety. They “had to learn from their own experience the difficulty of dealing with the Russians. They had to extend the hand of friendship and have it spurned.” In applauding President Harry Truman’s postwar policy of “firmness and preparedness”, the writer concluded bleakly that having gravely misjudged Russia twice in the past, “the western democracies cannot afford to make another miscalculation about Russia’s military power or political intentions. A third mistake might well be fatal to western civilisation.”

In the recent traumatic weeks since Trump assumed office, some commentators have argued that today’s Russia is not the old Soviet Union; that the betrayal of Ukraine, which has been inevitable for many months, need not bear adverse consequences for our own comfort and safety; that it is too late to reverse the Russian march towards victory; that we must resign ourselves to Moscow once more dominating a sphere of influence – a clutch of vassal states – around the Russian periphery.

World leaders must come clean

All these propositions seem deeply distressing to those of us who not only cherish our own freedoms but believe we must stand up for those of others if we wish to inhabit a half-decent world. But our political leaders of all parties must come clean about our own responsibilities, and our own failures, which have brought us to today’s sorry pass.

Trump speaks and behaves as an ignorant brute. But under any president the US has had enough of paying most of the bills for Europe’s security, as it has done since 1945. I have quoted before in The Times a remark of the last brilliant US ambassador in London, Ray Seitz, when I mused to him back in 1992 about what sort of world we should in future inhabit when post-Cold War America exercised sole hegemony. “That presupposes,” said Ray drily, “that the United States is willing to exercise such hegemony.”

He saw three decades ago that Americans were tiring of playing the world’s policeman. In the same conversation – and remember, this was under a Tory government – he said how foolish Britain was to slash its armed forces when our military prowess commanded global respect and gave us a genuine claim to “punch above our weight”. He would never then have guessed that in 2025 those same armed forces would muster just a quarter of their waning 1992 strength.

Finally, Ray Seitz said to me: “Never forget that the United States is interested in Britain only insofar as Britain is a player in Europe.” It is today a serious problem that as Sir Keir Starmer’s government strives to persuade other European nations to reinforce their military strength to compensate for threatened American retreat, since Brexit we are almost bereft of moral authority on the Continent.

In dealing with Trump, the British and other allied governments have no choice save to respond to his insults with measured words: to turn the other cheek, while yielding nothing in our support for Ukraine. As mere citizens, however, the rest of us have no duty to hold back. We must keep saying again and again that Trump’s rhetoric about Ukraine – and Gaza – is a tissue of lies and fantasies. There is no plausible mitigation for the president’s language and for his apparent personal sympathy for the murderous Putin.

We must rearm, and it will not serve to say that there is no money. It is true the public finances are in parlous condition but ministers must summon the words and indeed the passion to explain to the British people why we must spend less on other things in order to rebuild our threadbare defences, because security is rightfully the first call on a nation’s finances.

We must strive against the odds to persuade our European neighbours that we cannot stand by and see Ukraine suffer a Russian evisceration mandated by a monumentally deluded American government. In the 21st century it is usually deplorable to reprise the language of WWII, but Churchill’s great defiant phrase, “if necessary, alone”, suddenly possesses a new, chilling resonance.

Here is one more quote from Chester Wilmot back in 1952. He wrote that Washington’s refusal to take account of postwar political imperatives, “the cause of so much of Europe’s present suffering, had its origin partly in the immaturity of the Americans and partly in their history”. There really are parallels between then and now.

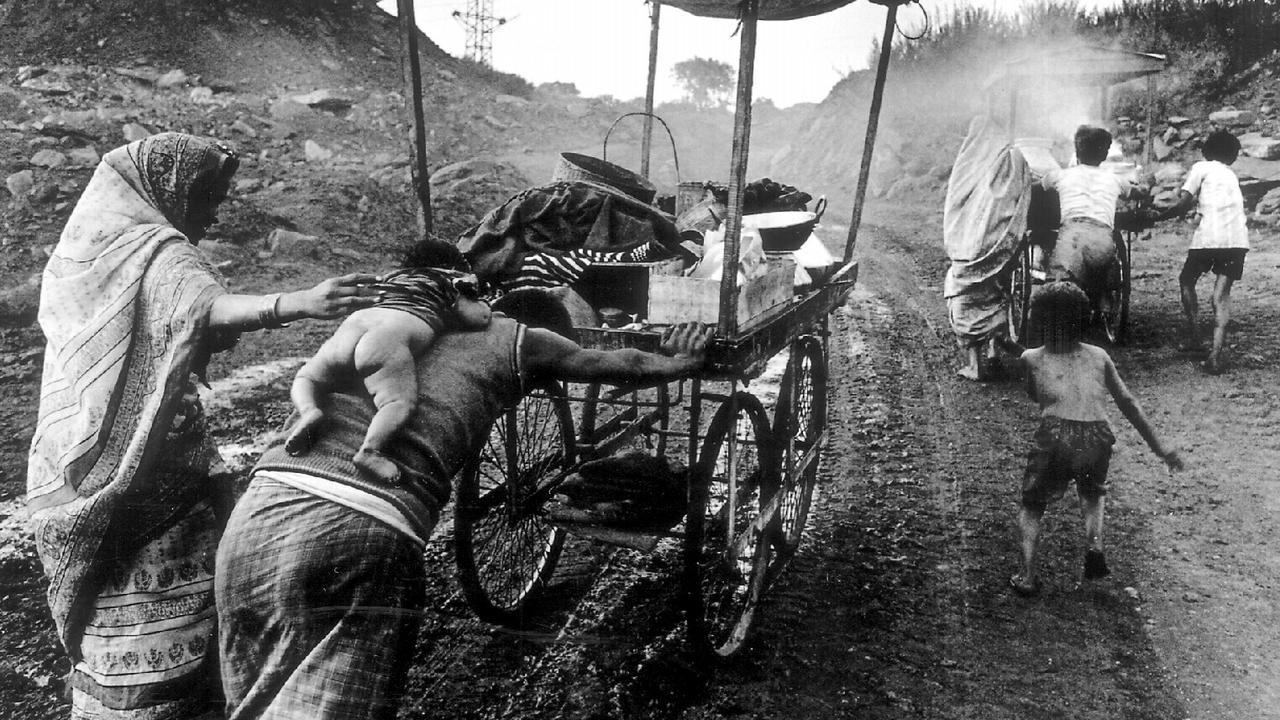

Before the second Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Ukrainian novelist Andrey Kurkov wrote a deeply moving novel, Grey Bees, about what life was then like in the “Grey Zone” of the Donbas, where Moscow-backed separatists exchanged fire daily with Zelensky’s forces and Russian-empowered atrocities such as the 2014 shooting-down of a Malaysian airliner went unpunished. Kurkov wrote a new foreword in 2022, which concluded: “The climax of Putin’s dream is approaching – the reunification of Russians, Belarussians and Ukrainians. We have to awaken him from his dream … Ukrainians will never agree to become subjects of a Russian empire. We cannot back down.”

Most of us now feel stunned, not by the words and deeds of Putin, to which we have grown grimly accustomed, by those of Trump, as leader of the free world. We surely cannot allow Andrey Kurkov and his people to be betrayed by the US and the unworthy hands into which its leadership has fallen, even if it is frankly hard to see how we Europeans can save Ukraine if the Americans indeed walk away.

Yet it would be dishonest of me, towards the end of this pretty grim assessment, not to cite some counter-arguments put to me this week by an Australian analyst whom I respect, who urges against panic. He reminded me, first, that before damning Trump for reaching out to Putin we should consider that Eisenhower invited Khrushchev to Washington within three years of Russian tanks suppressing the 1956 Hungarian uprising.

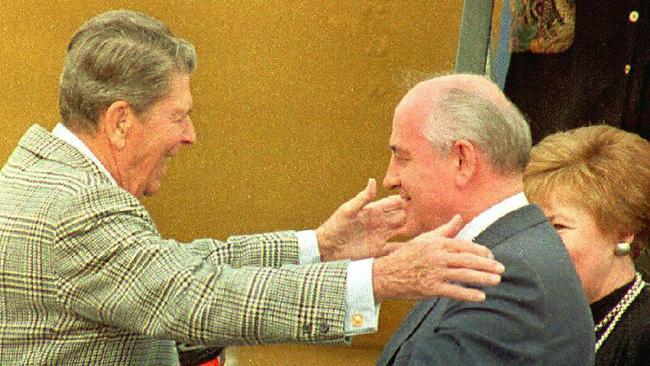

Nixon started detente with Brezhnev in 1972, four years after the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia. Reagan met Gorbachev in Reykjavik in 1986 while the Russians were still fighting American-backed mujahideen in Afghanistan. All three approaches, my Australian friend observes, were applauded as representing realpolitik.

Russia is today weak, he added, while China is the real enemy because it is strong. He concluded: “Trump’s foreign policy is a work in progress and there is a strong case for ending the Ukraine crisis now.” He himself does not believe that anything Trump is doing threatens the US-UK-Australia alliance against China.

I disagree with my friend. I do not believe anything Trump is doing is guided by a coherent foreign policy vision beyond that of his own self-aggrandisement. Some of us have feared since 2022 that the Ukraine war would end in “a dirty deal” – a phrase I then used in The Times – because I did not believe Zelensky’s people had the military strength, alas, to achieve absolute victory.

But there is a very long march between believing that concessions will have to be made in negotiations with the Russians, and – as Trump and his people have already done – publicly conceding everything before the Russians have offered anything.

Cold War age of smart diplomacy

During the Cold War, every US president, including the three mentioned above, was guided by seriously smart advisers pursuing a deeply considered policy in which diplomacy was supported by military strength. Today, America’s armed forces are in a sorry condition, with army recruitment languishing and many warships unfit for action. Worse, America’s armaments industries have atrophied and China is outbuilding the US in every kind of weapon system – even threatening its dominance of artificial intelligence.

Worse, Trump has nobody advising him of the same brilliance as Henry Kissinger, supreme cynic though Henry was, or Reagan’s secretary of state George Schultz, or his defence secretary Caspar Weinberger.

The Trump administration appears to be working from the same clumsy assumption as Putin - that might is right. Of course, this has been true in some measure throughout history but the president’s claim that Ukraine’s national leader bears responsibility for his country’s invasion by the Russians must never be allowed to pass as other than contemptible.

In a newly uncertain world from which order and stability have been banished, the only certainty is that it is vital for Europe dramatically to increase its defence spending. If this is not done, our continent will remain naked not only in the eyes of our foes but also of the US.

There is a real danger that Germany, Italy and Spain will remain supine, clinging to the cold comfort that neither the Russians nor Chinese are likely to invade them. But if Britain is again to hold up its head in the world, we must restore credibility to our armed forces, such as today they lack as a consequence of the policies of both Tory and Labour governments over more than three decades.

Yet finally, difficult through it may be in this sorry week for the values of freedom and decency, we must keep telling ourselves that we should never give up on the US. It remains the greatest nation on earth, even if today it appears to have fallen into unwelcome hands.

For the here and now, Europe must strive to save Ukraine from Trump as much as from Putin. But for the future, the American genius – and I use the word advisedly – remains the best hope for the light and leading of the West through the balance of this century.

Today we face some ugly realities across the Atlantic. We must respond with a measure of courage – not the physical courage of those who are being asked to fight, to go to war, as thankfully we are not, but the moral courage to forswear despair. Those of us who, in the past, have witnessed the United States suffering bad times, for instance in the Vietnam era, have also seen it come through them to experience repeated reinventions. Americans have an extraordinary capacity for self-renewal.

The rest of us must continue to cherish hopes that good, honourable and even noble times will come again to restore the world’s greatest democracy, and its leadership of the West, and meanwhile strive to help ourselves and the people of Ukraine, even if Donald Trump is unwilling to do so.

The Times

This is likely to go down in history as the week in which the president of the United States drove the post-1945 security architecture of the West to the brink of a precipice. We cannot be certain that a worst-case outcome – the sellout of Ukraine – will happen. Such sages as the former prime minister Boris Johnson urge that Donald Trump speaks as recklessly as he does only to shock friends and foes towards a peace deal.