The Mancunian candidate: How a former City striker became president of Georgia

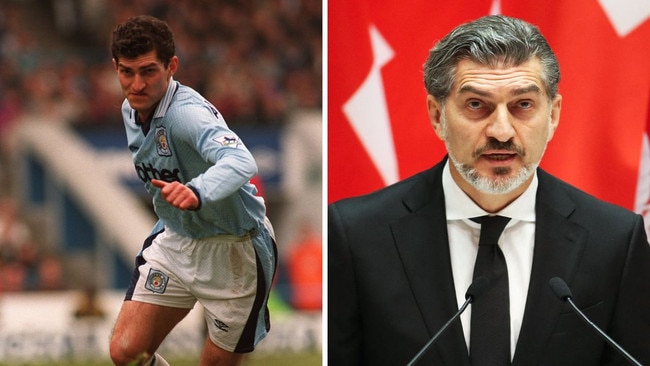

Mikheil Kavelashvili, who played for Manchester City in the 1990s, has been sworn in as president of Georgia. Protesters believe he is a puppet of the country’s richest man who wants to return the nation to Russia.

Flanked by twinkling fairy lights and the national flag, a dark-suited man with a black goatee beard stood outside a palace on Tuesday night to address his compatriots.

A former professional footballer in Britain in the 1990s, Mikheil Kavelashvili, 53, is now playing a more dangerous game for far higher stakes. Just two days earlier the populist anti-western politician had been inaugurated as the new president of Georgia, a volatile Black Sea nation bordering Russia.

In his televised New Year’s Eve remarks to the nation, he sounded optimistic. “I believe this will be a year of good triumphing over evil,” he said.

But many of his countrymen fear it might be the other way round.

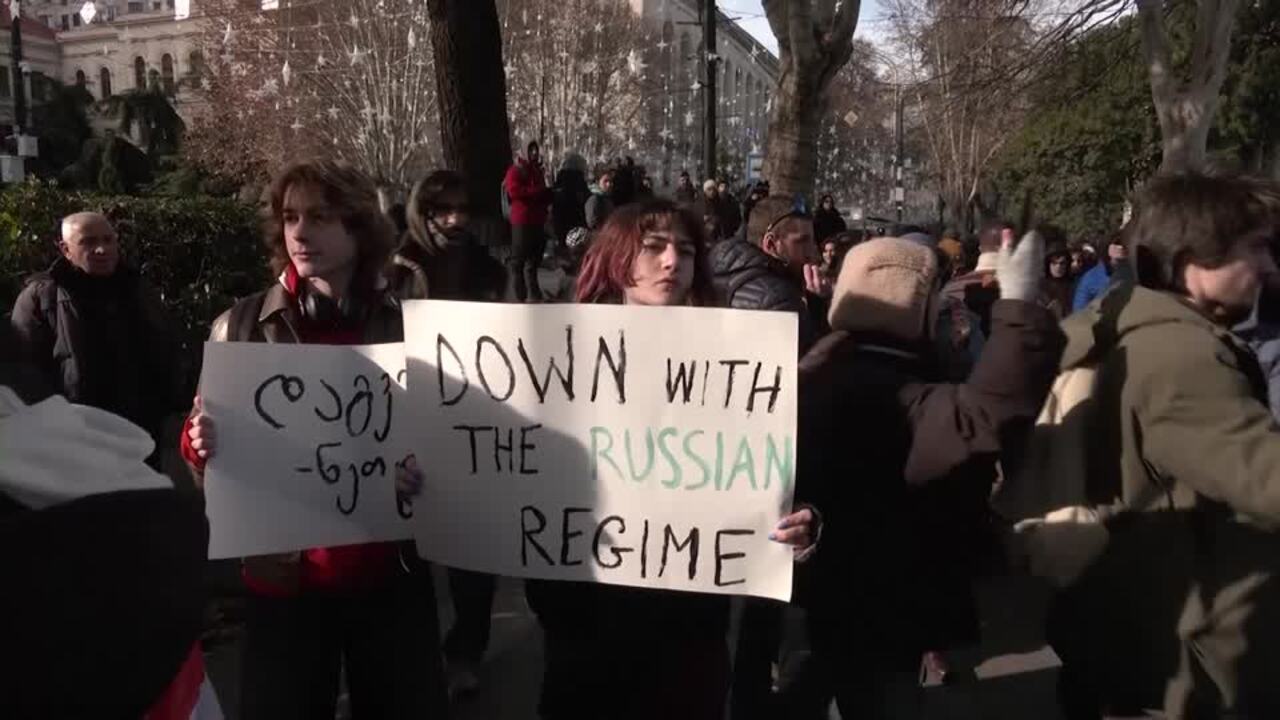

Protesters who oppose his elevation have filled the streets for weeks, while his pro-western predecessor, Salome Zourabichvili, has refused to recognise him as president. They think the former Manchester City striker is part of a Russian plot to draw their country, once regarded as a jewel of the Soviet empire, back into Moscow’s suffocating embrace.

Until very recently Georgia was seen as a crucial haven of democracy in the mountainous Caucasus region. A year ago the EU formally recognised it as a candidate for full membership. Now it is Vladimir Putin who appears to be winning the battle for influence there.

Beneath the surface of the footballer’s extraordinary rise lies a murky narrative intertwining power, money and a reclusive yoga fanatic and billionaire named Bidzina Ivanishvili, widely believed to be both a Kremlin ally and Georgia’s most influential man.

After making his fortune in Russia, Ivanishvili returned home and was briefly prime minister more than a decade ago, but his real power has been exerted behind the scenes, as the puppet master of Georgia’s politics. It was he, by all accounts, who selected the former City player - “the Mancunian candidate”, as a local wag put it - as president.

In Tbilisi, a city of 1.3 million people ringed by snow-flanked mountains, there are no expectations that the new president will put Georgia back on the road towards Europe.

Kavelashvili is known for parroting Russian propaganda about the morally decadent West and for foul-mouthed tirades against fellow MPs that have led to scuffles (in contrast to his conduct on the pitch, where he was never sent off).

For some analysts, Kavelashvili’s ascension was a clear sign of his patron’s scorn for the presidency.

Ghia Khukhashvili, a former adviser to Ivanishvili, likened the appointment to the story of the Roman emperor Caligula making his horse a senator. “A horse might have been more competent than Kavelashvili,” he chuckled.

Giorgi Gakharia, the country’s prime minister from September 2019 to February 2021, also put the boot in. “With his lack of education, experience or competence, he’ll be easily managed, he’ll fulfil instructions without question,” he said of the ex-player. “He’s decidedly average, just as he was on the football pitch.”

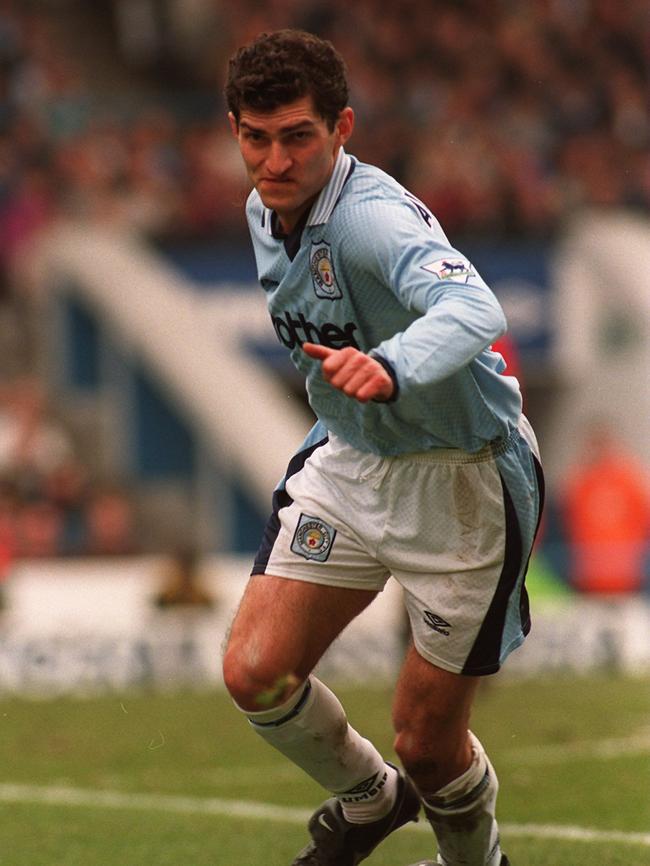

The new president’s nomadic footballing career was hardly glorious. After making his senior debut for Dinamo Tbilisi in 1991, the year Georgia won its independence from the Soviet Union, he was loaned to the Russian club Spartak Vladikavkaz in 1995 before being sold to Manchester City in 1996 for $3.3 million.

The club seems to have been influenced in its choice by its star player, Kavelashvili’s compatriot, Georgi Kinkladze, but he struggled to live up to his price tag. “He didn’t have Georgi’s skill, but few players did,” said Niall Quinn, a former teammate. “He was honest and hardworking ... not one for the bars.”

The two Georgians could not save the team from being relegated that year. “I recall our time together in the City team with nostalgia,” said Kinkladze, who these days owns a wine bar in Manchester. “The reason why his spell in the City shirt wasn’t as fruitful as it could have been was due to three factors: he arrived late in the season, we changed three coaches and he had injuries.”

Kavelashvili scored a solitary Premier League goal (against arch-rivals Manchester United) and was then loaned to Grasshoppers, a Swiss premier league team.

He retired from football in 2007 and applied for a job as head of the Georgian football federation but was turned down on the grounds that he lacked the necessary educational qualifications. From there he turned to politics.

Married with four children, he was elected to the Georgian parliament in 2016 as a member of Georgian Dream, a party that has won every general election since it was set up by Ivanishvili in 2012. “We wanted a more liberal society with closer ties to Europe, that was the dream,” said Khukhashvili, the former adviser to Ivanishvili.

To many of the protesters, the party seems to have morphed into Georgia’s nightmare. In May, it passed a law requiring organisations receiving funds from abroad to register as “foreign agents”, a ruse used by Moscow to intimidate pro-democracy activists. The EU saw this as evidence of Georgia backtracking on promises to reform.

Then the general election in October was tarnished by widespread and plausible claims of ballot-rigging, threats to ban opposition parties and intimidation of voters, which prompted the European parliament to reject the result and call for another election. Salome Zourabichvili, the outgoing president, also cried foul.

Georgian Dream suspended accession talks with the EU, prompting huge protests in Tbilisi and other cities. Police have responded with thuggish ferocity. Amnesty International reported “numerous instances of torture and other ill-treatment, several of which also revealed the organised and systemic nature of these abuses”.

Kavelashvili, who in 2022 set up his own movement, People’s Power, an offshoot of Georgian Dream, was directly appointed to the presidency on December 14 by a 300-seat electoral college dominated by MPs from Georgian Dream. He was the only candidate on the ballot. It was the first time a president had been appointed by officials rather than the people of Georgia.

After he was sworn in he signed into law a series of measures that make it harder to protest, including fines for using fireworks, blocking roads or painting anti-government graffiti on walls.

Giorgi Margvelalashvili, an academic who was president of Georgia from 2013 to 2018, called Ivanishvili and the new president part of a “special Kremlin operation” to put Georgia under Moscow’s sway. “They rigged the elections and have effectively said goodbye to Europe. Who will benefit? Only the Russians.”

He said that he too had been hand-picked for the job of president by his former friend, Ivanishvili, but at least had been obliged to undergo an election, which he won with 62 per cent of the vote. Ultimately, he says, his friend betrayed him: “He assured me he was withdrawing from politics but a few days after I was appointed he was micro-managing everything.”

He believes Ivanishvili “could have had a secret relationship with Putin all along” and predicts he will end up fleeing to Russia under pressure from protesters, comparing the billionaire to Viktor Yanukovich, the Ukrainian leader overthrown by the Maidan revolution in 2014.

With an estimated fortune of $11.3 billion, Ivanishvili lives in a futuristic, glass-domed mansion overlooking the city. It is often compared to a Bond villain’s lair, not least because of the glass tank filled with sharks that lines one wall of his study. “They’re intended to make the point he’s an apex predator,” said Khukhashvili, his former adviser.

Last week, the United States imposed sanctions on Ivanishvili. Antony Blinken, the secretary of state, said he had “eroded democratic institutions, enabled human rights abuses and curbed the exercise of fundamental freedoms in Georgia”. The EU tried to introduce sanctions but was blocked by Hungary and Slovakia, trusted allies of the Kremlin.

What is clear is that Georgia’s future is on the line.

“Do we end up with Belarus on the Black Sea?” asked Lincoln Mitchell, an American former adviser to Ivanishvili. “Ivanishvili could ask [the Belarusian dictator] Lukashenko and Russia for help. Security forces have remained loyal until now, though, so he may not need help.”

Other observers believe Putin was determined to pull Georgia into his orbit before opening negotiations with Donald Trump over ending the war in Ukraine.

“He doesn’t want Georgia to be on the bargaining table,” said Khukhashvili. “Georgia is the pearl in the Russian crown - Russians are excited by the idea of getting back their beautiful backyard.”

The protesters on Rustaveli Avenue, the capital’s main thoroughfare, insist this will not happen. “We will not let this stand, our future is with Europe,” said Tamar Areshidze, 34, a shoe designer, at a rally outside the parliament building on Thursday.

As Tamar spoke, a high-pitched cacophony of whistles cut through the air as though calling out Kavelashvili for a foul on the political pitch. Some of the protesters held up red cards.

Additional reporting: Vazha Tavberidze and Paul Rowan

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout