The first foreign-born sumo wrestler to become one of the Japanese sport’s grand champions

American-born Chad Rowan was considered too tall to be a sumo wrestler, but he confounded his critics and won admiration for humility and dignity as well as his powerful performances.

For an American wrestler to be accepted in the elite world of professional Japanese sumo was unusual. For Chad Rowan to attain the sport’s highest rank of yokozuna (grand champion) was unprecedented.

At 203cm tall and with a peak weight of more than 230kg, the Hawaiian-born wrestler, who fought under the name Akebono Taro, certainly had the physique to take on Japan’s strongest rikishi (sumo wrestlers) – up to a point. Although he was one of the tallest and heaviest wrestlers in sumo history, long legs traditionally are considered a disadvantage in the ring as a fighter can become top heavy and those with a lower centre of gravity are less easily thrown.

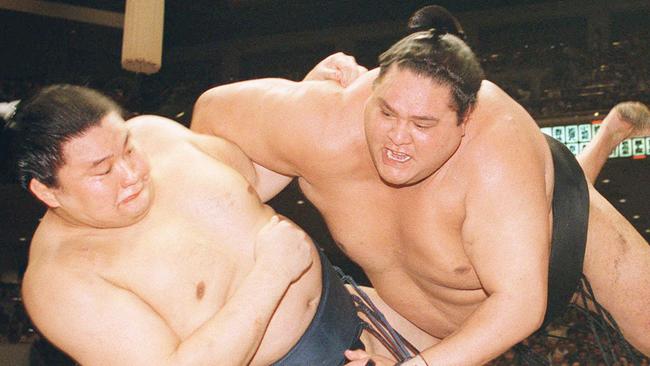

Akebono (it means new dawn in Japanese) negated this supposed drawback through his sheer aggression and ferocity, using his weight and power to push his opponents out of the dohyo (ring) with a forceful shove known as oshi-dashi or a variation called tsuki-dashi, a thrust he executed as if making a two-handed American football throat tackle.

He also used his long reach to grab his opponent’s mawashi (the 9m of silk loincloth wrapped around a wrestler’s waist) and in a move known as yorikiri force his opponent from the ring. “We were just brute strength,” he said. “We won fast or we lost fast. We weren’t too technical.”

After attaining the rank of grand champion in 1993, he remained at the top until 2001, winning a further eight tournament championships despite being plagued by injuries. His rivalry with brothers Takanohana and Wakanohana, fellow grand champions and local favourites from a famous sumo family, gripped Japanese television viewers and was credited with widening interest in the sport beyond its traditional base.

When he won, Japan took him to its heart and he returned the honour by taking Japanese citizenship in 1996. “I wasn’t thinking, ‘I’m an American, I’m going to go out there, plant my flag in the middle of the ring and take on the Japanese,’ ” he told The New York Times.

His humility and dignity – qualities much prized in the sumo world – were greatly admired and he was chosen to represent his adopted country in 1998 when Japan hosted the Winter Olympics. He marched at the head of the Japanese team at the opening ceremony, then led other sumo wrestlers in a traditional ritual intended to cleanse the stadium.

“He felt he had to work harder than the Japanese grand champions and had to be recognised as being more Japanese than the Japanese themselves,” sumo journalist Shoko Sato, who knew him for more than 30 years, said. “He was only in his 20s at the time and it was a lot of pressure, so sometimes he would overdo it when he went out at night.”

If he perhaps drank a little too much sake on occasion, he had the consolation of knowing he didn’t have to concern himself with putting on excess weight. Professional sumo wrestlers are encouraged to consume 7000 calories a day, almost three times the male average.

One of his best years came in 2000, when he was injury-free for the first time since 1993 and won 76 out of 90 bouts, the best record of any wrestler that year. However, in 2001 he announced his retirement at the age of 31 because of chronic knee problems. “I feel pain even when I do not wrestle. My body no longer does what it is told,” he said.

On his retirement he was made an elder of the Japan Sumo Association and worked as a trainer. His success opened the door for other non-Japanese sumo wrestlers and those he coached included Mongolian wrestler Asashoryu, who followed him in becoming a grand champion. There have since been five other foreign-born yokozuna, four more Mongolians and another American.

On his retirement he also opened a restaurant in Tokyo. Its failure in 2003 left him in financial difficulties and forced a return to professional fighting, not as a sumo wrestler but as a kickboxer and in the American-owned WWE pro-wrestling franchise.

However, there was one last sumo bout in 2005, when he was challenged by former WWE world champion Paul Wight, known professionally as The Big Show.

The contest – part of a televised WrestleMania Goes Hollywood extravaganza that can be found on YouTube – lasted just 63 seconds. Although The Big Show at one point managed the considerable feat of lifting his opponent off the ground, Akebono then threw him out of the ring with a two-handed tsuki-dashi of astonishing power and speed. Wight later called it the “most embarrassing moment” of his career.

Akebono’s success as a sumo wrestler is commemorated in his native Hawaii by a life-size statue of him executing his celebrated tsuki-dashi, but he remained a Japanese resident and citizen for the rest of his life. Since 2018 he had been in poor health, confined to a wheelchair and reportedly suffering partial memory loss.

He is survived by his wife, Christiane Reiko Kalina, a teacher of Japanese of American extraction whom he married in 1998, their daughter Caitlyn and sons Cody and Connor.

Akebono was born Chad George Ha’aheo Rowan in 1969 in Waimanalo, Hawaii, the son of Janice, an office worker, and Randy Rowan, a taxi driver. At Kaiser High School his first sport was basketball and he was good enough on graduating to win a basketball scholarship to Hawaii Pacific University.

His interest in sumo was aroused by watching bouts on television and he was still a teenager when Azumazeki Oyakata, a sumo trainer who also originally hailed from Hawaii, invited him to Japan.

When he arrived in 1988 he knew little about the country and spoke no Japanese but learnt fast while living and training at Azumazeki’s stable, where, in line with sumo’s strict hierarchical structures, he acted as a cook and cleaner to the more experienced wrestlers.

His rise through the ranks was meteoric. After equalling the record for the most consecutive wins from debut, he was promoted with alacrity through professional sumo’s six divisions.

In 1991 he was one of the top 40 wrestlers chosen to participate in the first basho (grand sumo tournament) to be held outside Japan. The event was staged at the Royal Albert Hall in London as part of a four-month festival of Japanese culture.

Within five years of his first match, he had become a grand champion – only the 64th yokozuna in modern sumo’s 300-year history and the first foreign-born wrestler to achieve the title.

The Times