The End Times? Humanity has proved to be remarkably durable

Forecasting doom is very fashionable – just look at the non-fiction shelves of any bookshop – but the boring truth is institutions are remarkably durable.

The fashionable term – should you wish to forge a career coming over terribly serious on the international conference circuit – is polycrisis. It is a usefully impressive way of saying that everything seems to be going wrong all at once: pandemic, wars, autocrats, AI, climate change.

In the US, senior officials are reported to fear “epic concern and historic danger”. A scan of topical nonfiction at bookshops reveals the morose consensus of our public intellectuals: End Times, The Uninhabitable Earth, How Democracies Die, Why Empires Fall, Doom.

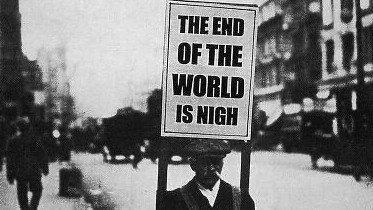

Does anybody think the world isn’t ending? The Doomsday Clock that purports to measure our species’ proximity to extinction is set at 90 seconds to midnight – its least cheerful prognosis yet. A recent survey of Americans found that 39 per cent of them believed we were living in the “End Times”. At certain Silicon Valley parties, tech bros have started introducing themselves with their names and “p(doom)” numbers, their personal estimates of the likelihood AI will destroy humanity.

For a while now it has been voguish to eyeroll at naive liberal fantasies of progress: the idea that society is fated for scientific, moral and political improvement until we all end up safe and dry on the right side of history. But – and I say this as a congenital pessimist – irrational faith in catastrophe is not necessarily any more sophisticated than blind optimism.

Some apocalyptic warnings, on the climate, for instance, should clearly be heeded. Others should fall under suspicion as plainly self-serving (Sam Altman’s OpenAI has been accused of using predictions of technological Armageddon to make ChatGPT seem more impressive and valuable).

And some Jeremiahs are just hysterical. Elon Musk’s wail that “the woke mind virus is destroying civilisation” is characteristic of an internet-poisoned mind that has learnt to interpret every problem as an apocalypse and every Twitter/X feud as a rehearsal for Ragnarok.

Almost every society in history has looked for the end times. The history of our prosperous and stable democracy is haunted with fears of collapse, revolution and crisis. Those on the right who fear the “death of the West” through decadence or the triumph of eastern powers repeat prophecies made regularly in the century since the publication of Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West. On the left, dreams of a final crisis of capitalism are as old as Karl Marx. An instructive Wikipedia page lists more than 100 apocalypses that (you will have noticed) have failed to come to pass. The belief that one’s own age is uniquely doomed is often a form of historical narcissism – the equivalent of the self-pitying egomaniac’s cry, “why does everything bad always happen to me?”

The underrated force in human history is stasis. Human culture and institutions are not inevitably the teeteringly fragile Ming vases we fear them to be. Sometimes they are capable of remarkable endurance. This is easier to grasp at a distance. In Rome last week, I visited the great fifth-century basilica church of Santa Maria Maggiore. Christian worship began there in the early 400s AD when pagan philosophers still taught in Athens. It continues a millennium and a half later while tourists scroll iPhones.

In his classic study of the late Roman Empire, The World of Late Antiquity, historian Peter Brown showed that an era once viewed as an age of calamity actually contained many remarkable continuities. For centuries after Rome’s classical apogee, its senators elected consuls, commissioned statues of themselves in togas and read the poetry of Virgil and Horace. “Byzantine gentlemen of the 15th century” wrote in the same “Attic Greek deployed by the Sophists of the age of Hadrian” who lived more than a millennium previously.

The formidable pace of the modern news cycle, which serves up new global catastrophes with every meal, obscures our own society’s deep continuities. We compel children to learn the words of a playwright whose works were first performed 400 years ago. Prime ministers have been succeeding one another peacefully for many years. Our monarchy is 1200 years old (and this story first appeared in The Times, a newspaper founded before the French Revolution). Things last.

This is not to deny that cities burn or dynasties fall, merely to point out that the drama of such events means they are fixed more forcefully in our minds than the stuff that quietly endures. The school curriculum (quite understandably) affords little sense that history deals in anticlimaxes as well as crises.

Compared with the horrors I might have expected had somebody told me I was fated to live through a global pandemic, the era of coronavirus now strikes me as unexpectedly banal. I don’t think it diminishes the pandemic’s tragedies to point out that for many people around the world the most important global crisis of their lives involved sitting at home patiently waiting for scientists to invent the necessary vaccine (which they did in record time).

To regard everything as a potential apocalypse is to risk becoming overwhelmed, dispirited or blinded to the crises that matter most. For all its present vogue, pessimism is not automatically the most sophisticated or the cleverest position. And that is hard for a pessimist to admit.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout