The egg race: scientists vie to create synthetic human embryos

An ‘embryo’ created without eggs throws up the mother of all philosophical and ethical dilemmas.

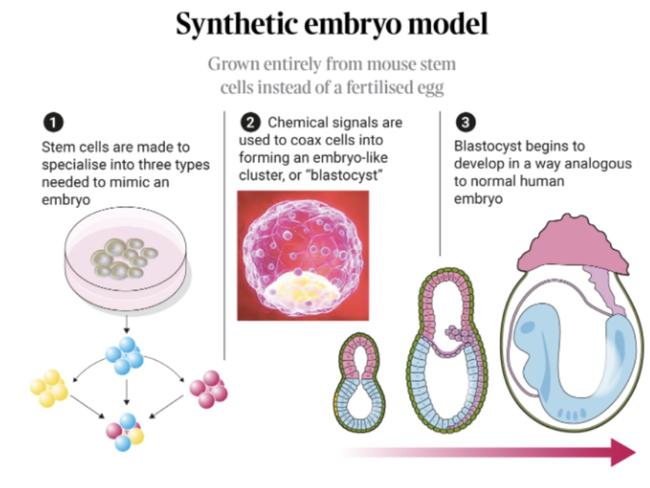

At first, the cells had no specialism. In a dish in a lab each had the potential, in theory, to become many different human cell types. But the scientists who put them there had specific plans. The cells were bathed in chemical messages, and began to organise: clumping, dividing and forming a structure.

There, in the laboratory of a Cambridge scientist, they arranged themselves: to mimic a human embryo. It was an embryo, though, that had never seen an egg or sperm. These “model embryos” were not real embryos. They could never become a baby, but – in results announced this week – they were recognisably embryo-like.

Now, if the announcement is to be believed, they will be used to help us better understand early pregnancy. They will also, however, accelerate an ethical debate.

There are many questions about the research, announced at a conference in Boston. How long could these model embryos, in theory, keep on developing? How useful will they be in their stated goal, to aid research to understand miscarriage in early pregnancy and improve IVF?

There is, though, another equally pressing question, one that scientists are now grappling with. What are they? Not in a biological sense so much as a philosophical one. Are “they” in any meaningful sense “us”?

For Professor Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, the scientist who announced the successful creation of the model embryos, the answer is clear: obviously not. “They look like embryos, they have a three dimensional structure like embryos,” said Zernicka-Goetz, who also has a position at the California Institute of Technology. “But,” she added, “they’re not embryos. It is important to be truthful.” What, then, are they?

The reason these models are needed is that, at present, we know very little about early pregnancy. Most miscarriages that happen, happen before you even know you are pregnant. They happen in the first few weeks. This is also the hardest time to study.

It is only legal to look at real embryos as they develop up to 14 days. Even then, very few are donated. But if we want more pregnancies to succeed, especially when using IVF, this is the period we need to investigate.

So rather than use a real embryo, the idea is that human stem cells – cells that can become other cells – can be used to make a model one, that can be poked, prodded and genetically tweaked, to understand the mysteries of our own development.

There are, though, paradoxes here. The need for the model embryos is prompted by the ethical problems of using real embryos. But their creation is itself an ethical conundrum.

The biggest conundrum of all is what, in a philosophical sense, are they? The truth is, said Sandy Starr, the deputy director of the Progress Educational Trust, a fertility charity, the question is unanswerable.

“There were several words for life in ancient Greek. One is zoe. One is bios. One refers more to biological life and one refers more to human life as lived, and they’re bound up with notions of personhood. The question of which form of life applies to reproductive materials is a very rich area for debate to which we do not have the answers.”

Clearly, said Professor Roger Sturmey, from Hull York Medical School, the fact they have not come from a sperm and egg is a big difference. For now, he said, if you wanted to get theological, you can easily make the case they have not reached the stage of “ensoulment”.

Up until the point an egg can split to make twins, some theologists have argued it cannot have a soul, because the soul would split. “It’s a philosophical and religious concept,” said Sturmey, adding, “Whatever ensoulment is.”

There is a less arcane interpretation of these answers. When biologists start having to quote ancient Greek or grapple with the matter of souls, it is a sure sign we are on the frontiers of epistemology.

For now, these concerns remain in philosophy. The fact that the announcement of success was made ahead of peer review, at a conference, meant that scientists could not scrutinise the data – which itself led to complaints. On Friday it was published, alongside another similar experiment from an Israeli team. Other researchers said that while clearly impressive, the model embryos were not going to fool anyone that they were the real thing.

Practically, few believe that the model embryos we have today could ever develop into a baby, even if anyone wanted them to. It may be, in fact, that different kinds of model embryos end up being used for different investigations – and that each never attempts to represent the entire embryo.

“These are models and so they are representations of reality, but they are not identical with reality itself,” said Christina Rozeik, the co-ordinator at Cambridge Reproduction. “In the same way as one of my son’s model aeroplanes is not an actual aeroplane.”

But here comes the second paradox. The better we become at modelling embryos this way, the closer we get them to take off, the more useful they become, the finer this distinction.

This “touches on a deep dilemma,” said Professor Hank Greely, from Stanford University. “We use models when we cannot ethically experiment on the originals, but as we make our models better and better, we risk backing into those same ethical constraints.”

He advocated more experiments in non-human primates to better understand the models. “I don’t have an answer to ‘what they actually are’,” he said, adding, “that’s the crucial question.”

Sturmey, Starr and Rozeik are part of a collaboration in Cambridge looking to explore these issues and lay down guidelines. Their hope is that, as with previous advances in fertility, the UK can work to develop the ethics in parallel. They will have a lot to consider.

Gunes Taylor, from the Crick Laboratory, said that one thing worth considering is we may have the question the wrong way round. Maybe we don’t need to debate what the stem cells are. Maybe we need to debate what we are.

“This is an opportunity for us to reflect on what exactly it is that we think it is that makes us human,” she said. “Our DNA? Growing in a uterus? The idea that we came from two parents, rather than a collection of lab-generated stem cells? We will need to get better at defining what we mean by human and decide what we think makes humans humans.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout