The Chinese dragon is running out of puff

Not this year, though.

The boom years seem to be over, overtaken by bad loans, bad demographics, bad local governance and broken dreams. Growth flags and the population is ageing. Hence two critical questions for outsiders. Have we reached Peak China? And if China turns inwards and enters a new national stasis, what happens to the great geopolitical rivalry of the 21st century?

The new-year trains home - said to be the biggest annual human migration on the planet - used to be cramped, three-day treks, with families sharing a single bunk. Now, pricey high-speed trains are the norm and few yearn for the old days. The modernisation of China may have stoked national pride and helped build a kind of legitimacy for the seemingly endless rule of Xi Jinping but it has also raised expectations about the performance of government bureaucracy.

Complaints are coming thick and fast and the new-year migrants are being viewed by the security apparat as a possible source of future political infection, just as they were once viewed as Covid-spreaders. Censors recently took down an online documentary, scathing on the lot of internal migratory workers, called Working Like This for 30 Years. They also sprang into action to muzzle an article which cited research that some 964 million Chinese people earn less than $280 (£223) a month.

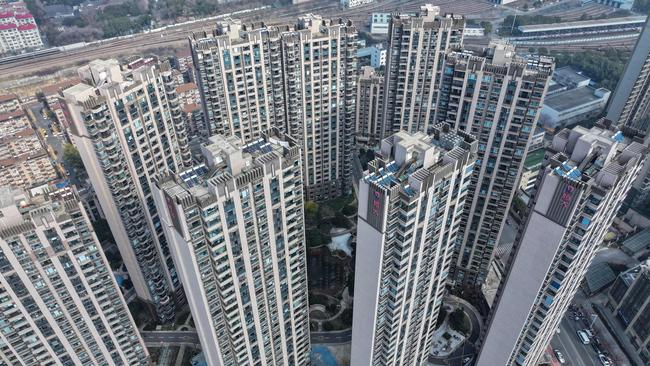

The accumulation of crises includes the implosion of the once high-flying property developer Evergrande, swamped by $300bn of debt. It has been ordered into liquidation and suddenly became a metaphor for everything amiss in the Chinese economy.

The tycoon class had become maximum risk-takers on the seemingly sure bet that the economy was on a one-way upward incline. Now they have been taken by surprise by Xi’s downturn. The ripples are spreading. Global investors once fearful of missing out on the Chinese bonanza - rapid growth plus domestic consumption pumped up by big ecommerce platforms - are scrambling for the exit.

A session held by Goldman Sachs in Hong Kong for traders, hedge funders and asset managers found in a poll that 40 per cent considered China to be “uninvestible”.

Beijing fan-boys say these fears are short-termist. In the second half of the 19th century, American railway entrepreneurs went bust yet the system they helped fund would turn the United States into the world’s top industrial power. Their advice: hang on and China will confound the doubters by winning a significant number of global rivalries (solar panels, electric vehicles). But that makes too many assumptions about the ability of Xi’s communist party to maintain trust and momentum. China isn’t merely experiencing a dip in growth, it’s in a state of neijuan.

The brilliant sinologist Ian Johnson translates that as “involution”, a turning inwards. He wrote: “The government has created its own universe of mobile phone apps and software, an impressive feat but one that is aimed at insulating Chinese people from the outside world rather than connecting them to it.” China is turning away from Hollywood movies - once assured box-office success - for homemade films depicting a stronger and more assertive China. Big hits include The Battle at Lake Changjin, in which the Americans are outsmarted and outfought in the Korean War.

The great involution doesn’t only mean finding Chinese heroes to stoke national morale. It also means squashing policy criticism lest this becomes a bridge between disgruntled students and workers - the driving force behind the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. The Xi regime has not moved on from this primal fear: that if market reform leads to demand for political pluralism, the Chinese communist party will be as doomed as Mikhail Gorbachev’s Soviet Union.

In a slowing economy Xi has limited options. He has chosen the national security route. Unable to offer a credible path to individual prosperity for young Chinese, their hopes of home ownership sunk by the fallout from Evergrande, he promises security in an unstable world. The security services are growing in political stature; interrogations and detentions are more common, digital surveillance ever more sophisticated.

The re-election of Donald Trump would probably be welcome to Xi, perhaps the new year’s gift he would value most. The Biden administration effectively barred the export of advanced semiconductors to China and is tripping up Beijing on artificial intelligence.

It is Biden who put together a global coalition to contain China and reduce dependency on the Chinese economy. It turns out that Trump, for all his bombast, was easier to deal with. Quietly, Xi is getting on with the steps needed to be a credible strategic power - including an anti-corruption purge of Chinese officers - but there is no sign yet of him moving on to a war footing against a more independence-minded Taiwan.

A war is not what the Chinese economy needs at the moment - but expect more strident nationalist propaganda at home, if only to deflect the attention of the Chinese people from their miserable plight.

The regime looks more vulnerable today than for decades - to social protest, to strategic miscalculation, to self-delusion. Xi learnt one vital lesson in 1989: that history only pretends to be long term and can, in fact, be a very sudden thing. That freezes him to this day.

The Times

China’s big annual holiday, the lunar new year, falls this weekend and it may bring some cheer to the millions of migrant workers travelling home to their families that 2024 is the Year of the Dragon, traditionally an auspicious time to make money and have babies.