The benefits and the surprise downsides in running to get fit

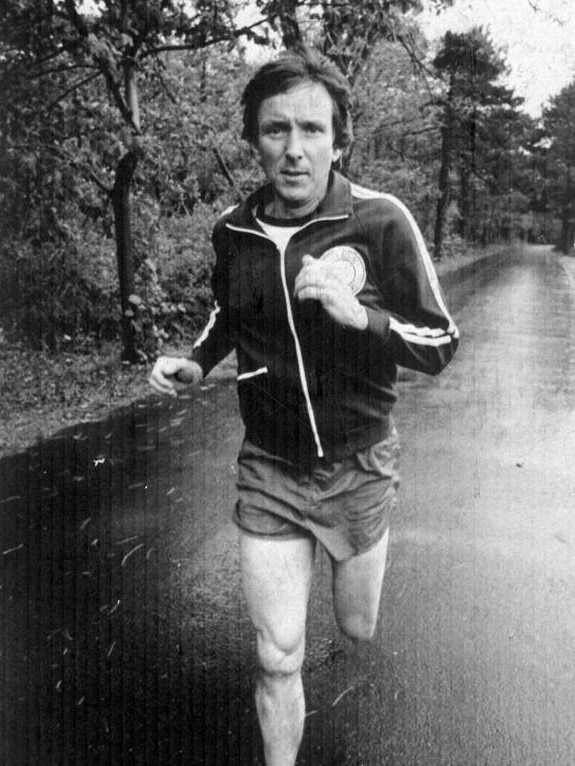

Ever since the guru of long-distance running, American author Jim Fixx, died while out for a jog, the costs and benefits or the sport have been controversial.

Thousands of Australians are well into their training programs for the capital-city marathon season next spring. With hundreds of kilometres already under their belts, they will attempt to cover the 42.1km fuelled by energy gels and sports drinks, and with body protection supplied by joint support bandages, Vaseline and blister plasters.

Distance running is known to be among the best ways to boost aerobic fitness, increasing the efficiency with which your lungs and heart operate. However, it also impacts arteries and joints, hearing and even your libido. We ask the experts how longer-distance running leaves its mark on body and mind.

You’ll turn back the ageing clock by four years

Training for and completing your first marathon will have a dramatic effect on your vascular age, which is strongly associated with a reduced risk of heart disease, dementia and kidney diseases. Professor Charlotte Manisty, a consultant cardiologist and researcher at the Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences at University College London and Barts Heart Centre in London, and her team tracked 138 healthy first-time marathon runners, testing them for six months before and after the events to study the effects on arterial stiffening, blood pressure and factors that contribute to vascular ageing.

Her results, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, showed long-distance running helped to reduce blood pressure and aortic stiffening. Participants experienced the equivalent of a four-year reduction in vascular age. The greatest age reversal was seen in slower, middle-aged men who started training with raised blood pressure. “Our study highlighted the importance of lifestyle modifications to slow the risks associated with ageing, especially as it appears to never be too late as evidenced by our older, slower runners,” Manisty says.

Your joints will absorb several tonnes of impact

An average runner covers just over a metre with each stride. Each stride loads the muscles and joints with forces equivalent to two to three times a person’s body weight.

The fewer strides you take, the better it is for your body – elite runners lengthen their stride for this reason. During the early stages of a marathon, on a typical run, each foot spends about 0.2 seconds on the ground and 0.5 seconds in the air, but the duration of contact increases as fatigue sets in. The more ground contact, the more loading through the body. For someone weighing 70kg, that means each stride can generate 226kg of impact force that travels up the shin, through the knee to the pelvis and trunk.

Research, outlined in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, has shown that if you run about 30km a week in training you can experience up to 1.3 million stride impacts a year and, over the course of a single marathon, the total pressure exerted can amount to several tonnes. Not that this translates into a greater risk of joint injuries, as it can offer some protection for joints by strengthening bone and muscle.

In the largest study of its kind, orthopaedic surgeons at Northwestern University in Illinois studied injury rates in 3804 midlife marathon runners. Their findings, published in Sports Health last year, showed the most significant risk factors for hip or knee arthritis and joint problems to be age, BMI, previous injury and family history – with no risk from long-term running.

Distance running can improve your hearing

In a study of 1082 women, researchers from Bellarmine University, reporting in the American Journal of Audiology, found those with the best cardiovascular fitness from activities such as running were also 6 per cent more likely to have good hearing compared with those who were unfit.

“Aerobic exercise will boost circulation and increase the supply of nutrients to the ears and ear canals, which boosts hearing,” says John Brewer, a professor of sport and author of Run Smart: Using Science to Improve Performance. “The wearing of headphones when running and playing music too loudly in them can have an adverse effect.”

Your memory and mood will benefit

Running produces a flood of chemicals and hormones that boost brain health and mood. These include release of dopamine, the “happy” hormone, which is also involved in controlling movement, motivation and learning as well as exercise-induced increases in a dopamine-triggering chemical called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).

One study at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, found distance running to produce a 40 per cent increase in dopamine and a 60 per cent increase in BDNF compared with non-running controls.

“Regular running also enhances blood and oxygen flow to your brain,” says Brewer. “That strengthens neuron connections and helps to improve focus, memory, thinking powers and performance in cognitive tasks.”

There’s a higher risk of iron deficiency for distance runners

Small amounts of iron are lost through sweat in any intense long-duration exercise. Iron can also be leached through the gastrointestinal tract as the activity draws blood away from the gut, which can cause reduced blood levels of iron over time.

Jessica Hill, an associate professor in applied sport and exercise physiology at London’s St Mary’s University, says there is some evidence that long-distance runners are prone to “foot-strike haemolysis”, where red blood cells are damaged by the feet repeatedly hitting the ground over many kilometres of marathon training.

“Squashing of the capillaries in the toes as you land on each stride can damage blood cells, reducing levels of haemoglobin, the part of the red blood cells where most iron is stored,” Hill says. “You can end up with very mild iron deficiency if your mileage is excessive.”

Eating plenty of iron-rich foods such as eggs, bread, beans, pulses and green, leafy vegetables is important.

You will probably shrink during a marathon

By the time you cross the finish line you could be a couple of centimetres shorter than when you started. This, Brewer says, is down to a loss of fluid in the 23 shock-absorbing discs in your spinal column that are designed to support the vertebrae.

“Most people lose some vertebral height with normal activity during the day, but the shrinkage is exacerbated when running long distances,” he says. “Dehydration combined with compression of discs with the force of your running strides is the cause.”

One study, in the Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise journal, showed that running for half an hour can reduce disc height by about 6.3 per cent. “That could mean a loss of 10 to 20mm,” Brewer says. “However, it is important to stress this is entirely temporary and normality will be restored within hours.”

Markers for cardiac disease will rise (but don’t be alarmed)

Early studies of runners in the 1979 Boston Marathon showed that levels of an enzyme called creatine kinase rose by as much as 2000 per cent after the race. Although it had returned to normal within weeks, it led to researchers speculating on a higher risk of heart disease.

“Creatine kinase is a marker for a cardiac arrest, but there are different types of creatine kinase and one type also sits within muscle cells,” Hill says. “During a marathon, small micro-tears to muscles cause temporary damage. This results in creatine kinase leaking out of muscle cells to sit in the bloodstream of runners, but it is not the same form of the enzyme that is associated with a heart attack.”

Men: expect your libido to slump. Women: it could affect fertility

The effort of training for a marathon could leave men’s libido flagging – on top of being too tired for sex.

Anthony Hackney, professor of exercise physiology and nutrition at the University of North Carolina, surveyed 1077 adult male endurance enthusiasts who participated in running, cycling and triathlons for a study in the Journal of Endocrinological Science two years ago. He found that men training for long-distance events such as a marathon had lower libido scores than those training for pleasure or for shorter distance events. The more marathons they ran, the lower their libido became.

Hackney’s research also highlighted that women who do a lot of prolonged, intense exercise may “have an elevated risk for developing menstrual dysfunctions and potential infertility”. He advised couples to tone down their endurance training if trying to conceive.

You could lose up to 4.5kg

Running a marathon is not a significant calorie-burner. Men will burn about 3000 calories over the course, women about 2600.” This is equivalent to a normal daily intake for many adults, or the amount in a 35-40cm pizza.

Most of the calories used come from carbohydrate stored in the muscle and liver as glycogen. Although our body fat levels could sustain several marathons back to back, our glycogen stores (the main source of fuel for running long distances) can quickly run out. They need topping up with isotonic, carb-containing sports drinks, gels and bars throughout the marathon distance – so you are consuming calories as well as using them up. Still, by the end of a marathon runners do typically weigh 4-5kg less. “Much of this will be fluid,” Brewer says. “And you will likely regain most of that when you drink, eat and refuel over the coming hours and days.”

You will become a more efficient breather

The strain on the respiratory system during a long-distance running event is immense. Sitting on the sofa we might take about 12 breaths a minute, but that rises to about 40 breaths a minute in and out of a marathon runner’s lungs.

“As soon as you start running, there is an immediate hike in heart rate and breathing frequency,” Brewer says. “Not only do you breathe faster, but the ‘tidal volume’ – the amount of air travelling in and out of your lungs – also increases as your body provides more blood and oxygen to its hardworking muscles.”

Exercise physiologists estimate that marathon runners inhale and exhale about 18,000 litres of air, more than a sedentary person would breathe over two full days. “Runners become more efficient breathers over time and we tend to adopt the intensity and type of breathing we need to suit our pace and speed,” Brewer says. “Trying to force changes in breathing patterns can make running feel more like hard work, so just breathe as naturally as you can.”

Sweat is lost at rates of one to three litres an hour

Body heat rises steadily when we run. Without the body’s in-built cooling mechanism of sweating we would quickly hit intolerable heat levels.

“Sweat can evaporate from the skin at rates of one to two litres an hour, and up to three litres an hour in hot and humid conditions. We also lose moisture with every breath we exhale, even on colder days,” Brewer says. “While runners need to sweat to avoid a rise in core temperature, the loss of body fluid can affect physical and mental performance.”

Once 2 per cent of body weight is lost through sweat it can lead to significant effects of dehydration such as confusion, headaches, cramps, fatigue and dizziness. “This could arise in less than an hour for some people,” Brewer says.

THE TIMES