Technique, not shoes: how to run like a pro

He has improved the gaits of the top athletes and studied some of Kenya’s finest long distance runners. Now Shane Benzie sees what he can do for the rest of us.

I’m a plodder, I tell Shane Benzie, after sending film of my running style, from three angles, to the man who coaches world record holders and ultra-marathon winners. He then slows the clips down and analyses my gait, frame by frame.

“I think ‘plodder’ is a bit harsh,” Benzie says. “You’ve absolutely got the arms bang on.” I feel a “but” coming. “But you’re hitting the ground and the impact and the deceleration is almost of a negative trajectory, which makes it feel as though you’re fighting the ground.” I need what Benzie calls “elastic energy”.

Benzie, 53, a technique coach, wants us all to run more like Kenyans, who fluidly stride through the Rift Valley and round the athletics tracks of the world. There is no reason why we shouldn’t be able to run like that. It’s just that in our sedentary modern lives we have forgotten how to do so.

He was briefly an ultra-marathon runner, but by his admission not a very good one. At the age of 41 he sold his company, which sourced car parts for garages, and went to the US to retrain as a running coach. He became disillusioned that technique work was based on athletes pounding treadmills and took himself off to study runners in Ethiopia, where he was mesmerised by the way they ran with their chests out “in a very synergistic, connected, and what looked like elastic way”.

He came home and studied myofascial anatomy. Learning about fascia, the stretchy tissue that wraps around and separates bones, muscles and organs, transformed his understanding of the skeleton. To him it is not a stabilising structure from which everything hangs, but a collection of bones that are “floating in this amazing sea of elasticity”.

He is talking via video call from the garden of a house in the Isles of Scilly, where he is spending the summer with his wife, grown-up daughter and grandchildren, but has spent considerable time in Iten, the Kenyan town that has produced an astonishing line of world-class athletes, including David Rudisha, the double Olympic 800m champion and world record holder. “These athletes were not being taught to move using a deeply considered philosophy,” Benzie writes in his new book, The Lost Art of Running, “they just ran.”

In the modern world, he believes, there is an epidemic of poor running. In the Ugandan countryside he studied farmers and labourers who moved with the same ease as Kenyan runners, but in Kampala the office workers were just as slumped and lacking in elasticity as in Britain.

“It was incredible. These are countrymen that live three hours apart, moving almost like a different species from each other,” Benzie says. He is convinced that sitting is so bad for our postures that it will soon be classed as a disease, and he is an advocate of standing desks.

Benzie has concluded that we should “run tall”, the phrase Wilson Kipsang, a former marathon world record holder, used to describe his style when Benzie worked with him in Kenya. And when our feet hit the ground they should touch down on the natural dome formed by the arches in our feet.

A heel strike is the worst way to dissipate impact and leads to a greater level of deceleration. Mimi Anderson is an endurance athlete who held the record for running from John O’Groats to Land’s End for many years. During an attempt to run across America she suffered a serious knee injury. Benzie worked with her on her recovery and found that even an athlete of her experience had a strong heel strike on the right leg, the one with the knee problem.

To maintain balance and symmetry in our movement, Benzie advises us to avoid exclusively using our favoured stabilising leg when pushing off over obstacles on a path and even to make sure we don’t always lean on the same leg when waiting for the kettle to boil.

When I start running faster, the video shows that I extend my stride and my foot is landing too far in front of me, and this actually causes deceleration. What I should be doing is seeking to get more spring and height into my stride to go up and forward.

Many of us are so concerned about the impact of running on our knees that we shuffle with our feet close to the ground. It is an urban myth about running, Benzie says, that impact is bad. “Impact for runners is a beautiful thing because it turns into elastic energy and throws you forward,” he says. When the foot hits the ground, it can be used to create propulsion to drive forwards.

Top runners actually have more oscillation, or vertical movement, than average runners, and this helps them to cycle their legs underneath them and create a higher cadence. An optimum cadence is between 175 and 185 steps a minute.

“The harder they hit the ground, the more elastic energy they create, which throws them forward,” Benzie says.

Last year my shuffling attempt to protect my knees led to me tripping on a large stone on a towpath, falling flat on my face and fracturing two fingers. Fear of doing that again, and my generally hunched posture, means I run with my head down. “Boy, your head is super-low,” Benzie says. For every inch it goes forward and down, it puts another 10lb of weight on the spine. “Three inches down and the head has quadrupled in weight, and if the head comes forward you start to bend from the waist.”

We should keep our heads up, eyes on the horizon, occasionally looking down. “Anything that’s coming, you will track and jump over,” Benzie says. “We’re amazingly good at it.”

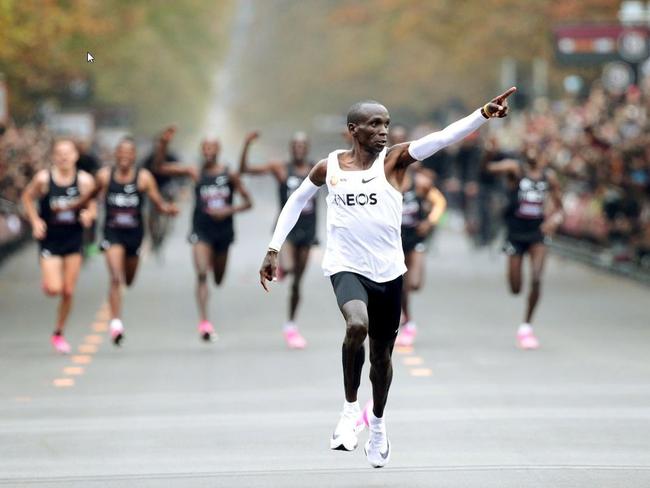

According to Benzie, Eliud Kipchoge had his head down when he became the first person to run a sub two-hour marathon last year because the Kenyan was surrounded by pacemakers obstructing his view. “The only time his head was in the position that it would be if he was running the London Marathon was when he broke away from them at the end.”

There are other factors that contribute to Kenyan running success, including genetics, living at altitude and the way the runners train together and support each other as a group.

Benzie met Kipchoge to discuss what made him a great runner. “He put it very much on the power of the group; hard work; God; lots of mileage. He wouldn’t put movement high on his list and yet actually he moves in a way that advocates absolutely everything that we do.”

Benzie studied young runners at a camp run by Brother Colm O’Connell, an Irish missionary credited with establishing Iten as the cradle of African running in the mid-1970s. At a training session with “the Yoda of running” Benzie was surprised to see runners warming up and then, after a whistle blew, taking off their shoes, chatting and even taking a nap.

“Brother Colm laughed and said the warm-up isn’t about getting the muscles warm and the cardiovascular system going, it is to get them relaxed. The more you relax, the better you perform. We’ve got it completely the wrong way round. We want it to hurt: ‘no pain, no gain’. For the Africans it’s about trying to relax and enjoy it.”

Benzie would like all of us to be as enthusiastic about the way we move as we are about new running shoes. “We like to buy our way out of trouble,” he says. “Do we want to take three months to change our movement, or shall we just order a box that we open up and put something on?

“When we were running around in Green Flash trainers and black pumps, nobody was really getting injured. If you put a lot of rubber under someone’s heel it is going to allow them to heel-strike. Putting an expensive pair of trainers on won’t make you land beautifully. You could run beautifully in a pair of wellingtons and really badly in a $550 pair of trainers."

The Lost Art of Running by Shane Benzie and Tim Major is published on Thursday (Bloomsbury)

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout