The real story behind Snake Island’s ‘heroic’ Ukrainian warriors

Like many tales told in war, the story of the Ukrainian outpost was halfway round the world before it began to be appreciated it was too good to be true.

Twelve months ago Yurii Kuzminsky was a fresh-faced soldier on a Ukrainian outpost almost unheard of by the rest of the world: he was the youngest marine on Snake Island, in the western Black Sea.

Then one day he was woken before dawn to be told it was under attack, and within hours he was hiding behind his barracks, eyes shut, praying for his life.

His account of that day does not sound like one of last-ditch resistance. But as he prayed, he also looked at his phone and found that his small unit of troops had become a symbol of the Ukrainian resistance.

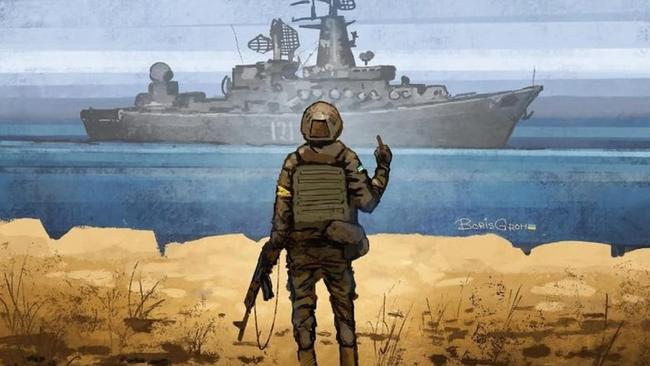

The phrase he read there – “Go f..k yourself, Russian warship” – had been uttered by one of his colleagues from the radio operators’ room a few hundred metres away an hour or two earlier. Kuzminsky had been completely unaware but the phrase would resonate across the world, feature on Ukrainian stamps, and even today makes him an accidental hero.

“It does make me happy that I am part of this story,” he said, recounting almost a year later what really transpired on the island. “It’s something to be proud of. The actual fight wasn’t equal – just ordinary guys against a warship. We couldn’t compete or take them on physically, but at least we did something.”

Like many tales told in war, the legend of the defenders of Snake Island was halfway round the world before it began to be appreciated that it was slightly too good to be true. It remains half true, though, and that is, as Kuzminsky said, something.

The story that was circulated last February 24 – and flooded the internet even while the Russian offensive to take the island was still under way – went as follows. There were 13 Ukrainian border guards assigned to Snake Island, a contested outcrop less than 2km wide, which sits close to the territorial waters of Romania and Moldova.

As Russian tanks poured over the Ukrainian borders in the north of the country, the warship Moskva approached Snake Island and demanded that the 13 surrender. Ukrainian media replayed over and again their response, picked up on the international shipping frequency channel 16.

“Snake Island – I, a Russian warship, repeat our offer: lay down arms and surrender, or you will be bombed,” the recording goes. “Have you understood me? Do you copy?”

One border guard is heard saying to another: “Well, that’s it then. Or do we need to reply that they should f. k off?” The second says, “Might as well”, and then the first comes out with his now famous response.

Not long after, the airwaves go dead. The Russians were already bombarding the island, and the world assumed that the 13 were all killed. The border guards were not dead, however. Nor were there only 13 of them. In fact, there were 80 men on the island: that number comprised 28 border guards – “we don’t know where the figure of 13 came from,” said Kuzminsky – along with 44 marines, six members of Ukrainian air defence monitoring radar screens and two civilians, a lighthouse-keeper and a port pilot. And they all survived.

When the radio exchange happened, Kuzminsky was with three other marines hiding behind one of the scattered barracks and administrative buildings on the island, 200m-300m from its jetty.

Aged only 20, he had never seen action before. He had little idea what was going on, apart from that the Russian paratroops were landing by boats at the jetty.

Russian jets were flying overhead, dropping bombs. There was already one Russian warship offshore, firing shells at them. They could see the larger bulk of the guided missile cruiser Moskva, flagship of the Russian Black Sea fleet, approaching.

“I was praying,” said Kuzminsky. “I just closed my eyes and waited.”

The marines did not, however, fight to the bitter end. As motor boats containing Russian marines drew up alongside the jetty, the order came through Kuzminsky’s headset to stand down.

“Our commander made a decision that in order to save lives he would surrender,” he said. The island’s defenders were armed with rifles and a few rocket-propelled grenade launchers. They had nothing to match the Russian firepower.

“The Russians said they would bomb the whole island to dust,” Kuzminsky recalled, adding that he thought about how little he had achieved in the 20 years of life that he believed was about to end.

The year since that moment has been painful for Kuzminsky and his colleagues. They were taken to Russian prisons, where they were beaten, given electric shocks and told they should accept Russian citizenship because “if they went home the Ukrainian side would shoot them”. They refused.

Kuzminsky was released in a prisoner exchange at the end of November. But half of the 78 military personnel on the island remain in Russian jails, and, Kuzminsky reckons, are still being beaten.

The identity of the radio operator who swore at the Russians has never been made public, for fear of retaliation from the Russians. Kuzminsky said he knew the man responsible – “a good guy, calm, and accomplished”.

He spoke to The Times from a rehabilitation centre, still recovering from his beatings in prison. But he will shortly return to his unit.

Would he return to Snake Island? He replied by showing a photograph of himself on the island, watching the sunrise. “It’s a very beautiful place,” he said.

Beautiful it may be but he is unlikely to go soon. It turns out that it is simply too easy a place to bomb.

Within a few weeks of their victory, it was the Russians’ turn to be on the receiving end of a crippling bombardment, its isolated occupants facing overwhelming odds.

Snake Island was said at its moment of fame to be strategically located. In fact, it proved worth sending warships to capture but not warships to hold.

The Moskva was sunk by Ukrainian missiles last April. In June the Russian occupiers withdrew. The Ukrainians sent a team to raise the flag again but they left immediately, and the island now belongs to its snakes. Or it would if there were any, but there are not. Even its name is misleading.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout