Secret Service agent Clint Hill tormented by JFK assassination

Clint Hill was just metres behind Kennedy when Lee Harvey Oswald opened fire. He probably saved Jackie’s life but was ‘consumed by guilt and anguish’ over the president’s death.

Clint Hill, a Secret Service agent, was standing on the running board of the car right behind John F Kennedy’s open-topped limousine when Lee Harvey Oswald fired his first shot at the president on that fateful afternoon of November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas.

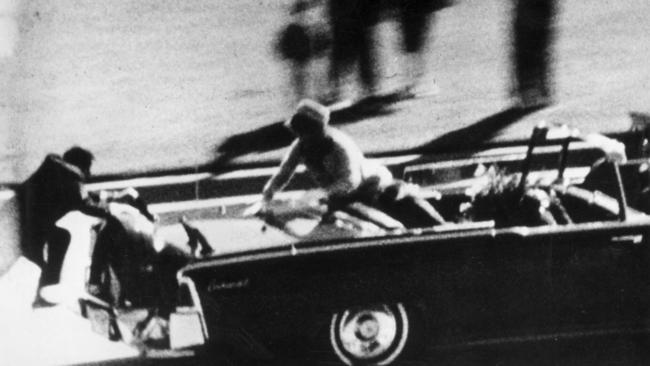

Hill saw Kennedy clutch his throat and lurch to his left. As he ran forward a second shot rang out. He grabbed a handrail on the limousine’s boot as a third shot hit Kennedy in the back of his head, shattering his skull.

As recorded in Abraham Zapruder’s harrowing home movie of that terrible event, Jacqueline Kennedy began climbing out of her seat. As the limousine surged forward Hill pushed her down, quite possibly saving her life. He then used his body to shield her and the mortally wounded president as the limousine sped away from Dealey Plaza. He remembered Mrs Kennedy cradling her husband’s head in her lap and exclaiming: “Jack, Jack, what have they done to you?” He recalled seeing “blood everywhere” and a “massive hole in the skull area; there was nothing there, no brain material”.

He screamed at the driver to get to a hospital, and gave a thumbs down to his fellow agents in the car behind, signalling that the president was very badly injured.

Hill had led the first lady’s security detail for three years. He had grown very close to her and understood her well. When the limousine arrived at Parkland Memorial Hospital she would not let the staff remove her husband. “It suddenly hits me,” he wrote in a memoir, Five Days in November, published on the 50th anniversary of the assassination. “She won’t let go because she does not want others to see the president in this condition. It is a gruesome scene, beyond the imagination. But worse, her husband’s normally sparkling eyes are unblinking, his magnetic smile gone.”

When Hill placed his suit jacket over Kennedy’s head, “she looks up at me and finally releases her husband”.

His duties were not yet over. As the doctors vainly sought to save Kennedy’s life, Hill received a telephone call from Robert Kennedy, the president’s brother and attorney-general. “How bad is it?” Kennedy asked. “I didn’t want to tell him his brother was dead. I didn’t think it was my place. So I said ‘It’s as bad as it can get’,” said Hill. “When I said that he hung up the phone.”

Hill was also told to find a casket for the president. He later helped to carry it on to Air Force One for the flight back to Washington, during which the vice-president, Lyndon Johnson, was sworn in as Kennedy’s successor. At one point on that flight Mrs Kennedy took his hand and asked: “Oh, Mr Hill, what’s going to happen to you now?” He was astonished. He wrote: “She has just witnessed her husband being assassinated and now must be present for the swearing-in ceremony of his replacement; her clothes are stained with the president’s blood and brain matter; she is making no attempt to change or clean up; and yet she is concerned about me, my future and my wellbeing. She is a remarkable lady.”

As it happened, Mrs Kennedy’s concern was not misplaced. Shortly after the assassination Hill received a presidential award for his “extraordinary courage and heroic effort in the face of maximum danger”.

He went on to serve three more presidents, but he was haunted by his failure to save Kennedy’s life, retired prematurely and very nearly drank himself to death.

Decades passed before he realised he could have done nothing to change the outcome. Mrs Kennedy had understood that almost immediately. Only days after her husband’s death, she sent him a handwritten note that read: “For Clint Hill – who did more than anyone to make my life with the President happy – and who guarded and protected him until the very end – How can I thank you? Jacqueline Kennedy.”

Clinton Jerome Hill was born in Larimore, North Dakota, during the Depression in 1932. He was the sixth child of Alma Peterson, an impoverished hotel maid who handed him over to an orphanage in Fargo. Three months later he was adopted by Chris Hill, a county auditor, and his wife, Jennie, both Lutherans who raised him in the tiny farming town of Washburn on the Missouri River. After high school – and service as an altar boy – he earned a history degree from Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota, then served as a counterintelligence officer in the US army before joining the Denver office of the Secret Service in 1958.

His first job involved protecting President Dwight Eisenhower’s octogenarian mother-in-law, a local resident, but a year later he was transferred to Eisenhower’s own security detail in Washington.

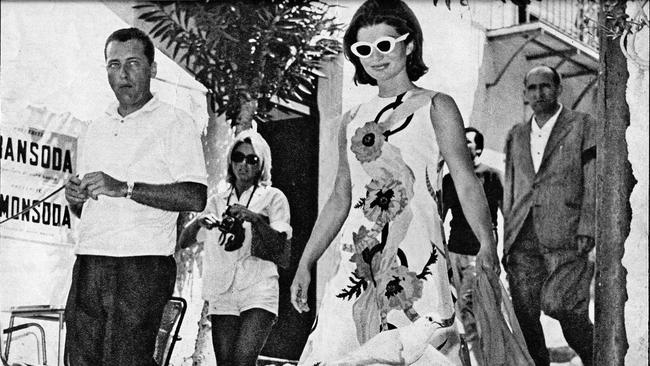

When Kennedy was elected president in 1960 he was disappointed to be assigned to protect his wife – “the Kiddie Detail” – but quickly realised his mistake. Mrs Kennedy was far from a traditional first lady. She travelled the world, loved sport and was almost as much of a star as her husband. They grew close despite their very different backgrounds. He was there when she gave birth to her second child, John, and again when she lost her third, Patrick. She trusted and confided in him. She tried in vain to teach him tennis. She was only three years older than him and they both had young children, Hill having had two sons with his first wife, Gwen, whom he had met at college.

“We were close, very close friends,” he said, though they always addressed each other as “Mrs Kennedy” and “Mr Hill”. He said: “I knew a lot of her secrets, and she knew all of mine.” Then, in November 1963, Mrs Kennedy decided to join her husband in Dallas for the unofficial launch of his re-election campaign, and both their lives were changed for ever. Hill continued to lead her security detail until the following year’s presidential election, though he was secretly tortured by feelings of guilt and at one point attempted suicide by walking into the sea fully clothed.

“Guilt and anguish consumed me,” he wrote in another memoir, My Travels With Mrs Kennedy (2022). “All I could think about was Dallas. It was like a movie playing over and over in my mind. I was running as fast as I could, my arms reaching for the handholds on the trunk [boot], but it was like my legs were in quicksand.”

He went on to lead President Johnson’s security detail, and Vice-President Spiro Agnew’s during Richard Nixon’s presidency, before serving as a Secret Service assistant director under President Ford. But in 1975 he failed a physical test and resigned – a tormented man – at the age of 43.

In a one-off interview at that time his eyes filled with tears as he suggested that if he had reacted “five-tenths of a second faster” he could have taken that third bullet and saved Kennedy. “That would have been fine with me,” he said. “I have a great deal of guilt … It’s my fault … I’ll live with that to the grave.”

Deeply depressed, Hill retreated to the basement of his home in Alexandria, Virginia, for several years, drinking heavily, chain smoking, seeing practically nobody and “trying to forget the painful past”. That changed only after a doctor told him he was killing himself, and he finally began to confront his demons.

In 1990 he revisited Dealey Plaza for the first time and explored the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository from which Oswald shot Kennedy. “That really helped me understand that I had done everything that I could have done … so that gave me some sense of relief,” he said. He began unburdening himself in interviews, and in several books co-authored by a journalist named Lisa McCubbin, whom he eventually married in 2021.

As the last surviving person in the president’s limousine that day, he also wanted to debunk the welter of conspiracy theories that have surrounded Kennedy’s assassination for more than 60 years. “It concerns me a great deal,” he told The Guardian in 2023. “There aren’t many of us left – very, very few – and eventually the way things have been going, those conspiracy theories are going to win out and take over.”

Hill had no doubt that Oswald had acted alone. The assassin was a loner and a loser, he told another interviewer, “because he just couldn’t get along with people, couldn’t keep a job, couldn’t even successfully defect to the Soviet Union – they didn’t want him either.

“He was just someone trying to make a name for himself and that’s what he did, but he didn’t live to relish his fame.”

Oswald was himself shot dead two days after killing Kennedy.

Clinton Hill, Secret Service agent at Kennedy’s assassination, was born on January 4, 1932. He died on February 21, 2025, aged 93

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout