JFK conspiracies found fertile ground in sloppiness and lies

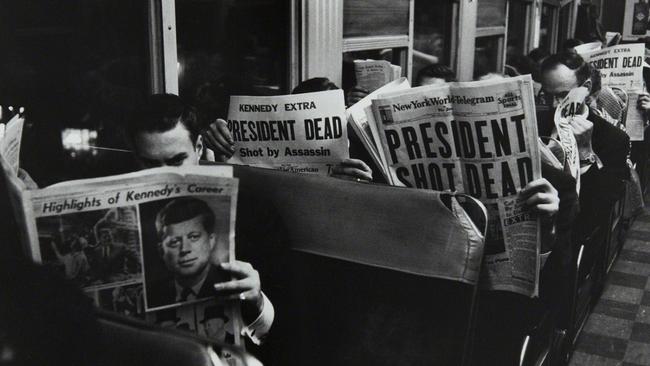

From the moment US president John F. Kennedy was assassinated 60 years ago today, conspiracy theories were rife - and no wonder given the sloppy investigations.

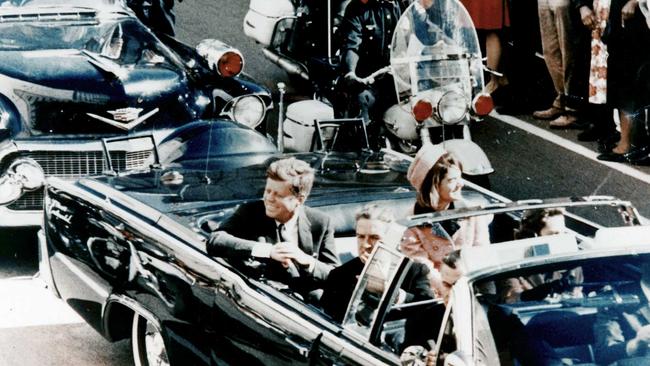

Sixty years ago on Wednesday, someone shot US president John F. Kennedy. The Dallas Police Department charged Lee Harvey Oswald with the crime.

The zealous communist was at the scene, had a gun, had a motive, hated Kennedy and killed a police officer while trying to escape the scene. All that sounds pretty incriminating. The Warren Commission that then investigated the president’s assassination interviewed 552 people, many of them witnesses, and examined 3154 exhibits – including the Zapruder film documenting the event in real time, and the gun and its bullets – producing an 888-page report that concluded Oswald was the killer and had acted alone.

So few believe that. Most Americans have long assumed more than one person was involved in Kennedy’s murder. Indeed, one retired American district attorney has compiled a list of everyone who has been claimed as Kennedy’s killer in the hundreds of conspiracy theories that have blossomed across six decades. It lists 86 names.

Before the Warren Commission report of September 1964, 29 per cent of Americans believed Oswald acted alone. In the immediate aftermath of the report this figure rose to 87 per cent. But since then, Americans – and much of the world – have stopped believing this. A poll this year showed 65 per cent of Americans thought the president was killed in a conspiracy.

The estimated 2000 books describing alternative theories clearly have had an effect. But the blame more likely lies in the vacuums – later filled with wild claims – created by sloppy police work, lazy investigations, unpardonable oversights in which evidence was mishandled and case files went missing (or were withheld), and often a lack of independent analysis of the facts.

It started from the moment Oswald fled the Texas School Book Depository building within three minutes of the killing. And the missteps quickly mounted as the president’s body was rushed to Dallas’s Parkland Hospital, where doctors described his shallow, fitful breathing and collapsing blood pressure as agonal – the brief, irreversible passage to death.

The Dallas Police Department and Dallas County Medical Examiners Office quickly lost control of events. The president’s murder, and that of JD Tippit, the 11-year police veteran shot dead in the street by Oswald 45 minutes later, were two of 113 murders in the city that year. Only one of those was investigated elsewhere.

A series of decisions was made – including mistakes by Dallas Police (most of whom appear to have handled the murder weapon), the Secret Service, the CIA, the FBI and, understandably, the newly widowed Jackie Kennedy – that could never be remedied. And they were made by people in positions where they would never pay a price for being wrong. And they never did.

Chief among these were files collected by the FBI, run then by its founder J. Edgar Hoover. The manipulative and much-feared Hoover had been boss of the FBI – and its forerunner, the Bureau of Investigation – since 1924. The dog-obsessive, never-married, alleged cross-dresser had files on everyone – including the philandering Kennedy. No president denied him more budget or staff as he collected even more awkward details on them. (Hoover’s FBI wouldn’t be beaten until former Beatle John Lennon took it on starting months before Hoover died in 1972.)

The FBI was critical to discovering Oswald’s motives and perhaps should have arrested him in Dallas in the days before the assassination. Its special agent James Hosty had been monitoring Oswald and his oddball contacts there for months.

Oswald, who had moved to Russia in 1959, then returned hopefully to relocate to Cuba with its less corrupt form of communism, had visited the embassies of both countries while in Mexico City in September 1963, most of his movements and even calls to those embassies being monitored by the CIA.

Early in November, annoyed at the surveillance of him and his family – he’d been filmed distributing leaflets for the group he joined, Fair Play for Cuba – Oswald had walked in to the Dallas offices of the FBI with a scrawled note: “If you don’t cease bothering my wife, I will take appropriate action.” The receptionist said he seems “crazy, maybe dangerous”. He had already purchased through the post his infamous Italian Carcano bolt-action rifle.

On the Sunday after the assassination, Hosty was summoned to his office, handed Oswald’s note and told to destroy it. He flushed it in the men’s toilet.

The CIA had never been made aware of it.

The president was shot seconds after 12.30pm. He arrived at Parkland Hospital at 12.36. He died moments later. His killer would die there 47 hours later. Kennedy’s most trusted military aide, Godfrey McHugh – once a boyfriend of the first lady when she was Jacqueline Bouvier – called Air Force One crew at 12.50 to advise they’d soon be returning to Washington.

Kennedy was officially pronounced dead 10 minutes later. At 2pm, after a heated debate between local authorities and Secret Service officers – the Dallas medical examiner and a Dallas police officer he summoned to help were pushed aside to allow the casket down the corridor – Kennedy’s body was illegally removed for transfer back to the plane. Texas law required it remained in the state for the autopsy.

McHugh stood loyally by his boss’s casket once it was loaded at the back of Air Force One where two rows of seats had been quickly removed to accommodate the unexpected load, but they still had to break off its handles to make it fit.

When they didn’t take off, McHugh went forward to speak to the pilot. He was concerned Dallas police would turn up to reclaim Kennedy’s body. There he found the soon-to-be-sworn-in president Lyndon Johnson hysterical in a toilet cubicle wailing: “They’re going to get us all. It’s a plot. It’s a plot.”

Having calmed down, Johnson was sworn into office at 2.38pm with Kennedy’s widow, in her bloodstained clothes, standing alongside. “Now, let’s get airborne,” he commanded, and Air Force One taxied for take off.

By the time it arrived at Andrews Air Force Base just outside Washington at 5.58pm local time (an hour ahead of Dallas), it had been decided where the president’s autopsy would take place. Jackie, appalled at the thought, had asked for there to be none. The president’s personal physician was Admiral George Burkley, like the dead president, a veteran of the US Navy in the Pacific. Kennedy was America’s first Catholic president (Joe Biden is the second) and the Catholic Burkley was trusted. But he made an odd suggestion: he explained that the autopsy could be performed at an army hospital or the navy’s, then reminded Jackie that her husband had been a navy man. Bethesda Naval Hospital it would be.

An ambulance took the newly damaged brass casket to Bethesda. In it was the body of perhaps the most famous murder victim of the 20th century, but the autopsy would be carried out by inexperienced doctors. Very few navy members are shot. The lead pathologist that night was James Humes. He had never performed a gunshot autopsy. His offsider, J. Thornton Boswell, also was surprised to be called in.

An army forensic pathologist, Pierre Finck, was summoned to help out. Finck agreed that it was unusual in such gunshot autopsies not to speak to the doctors who treated that patient up until the point of his death. He had spoken to nobody in Dallas. It also was common practice to examine the clothing of the deceased for indications of bullet entry and exit trajectories. He did not. Through the years he was reported as giving several explanations about the notes he took. There might have been one page, perhaps more. It seems he misplaced them and perhaps tried to replicate them from memory.

In 1996 he gave evidence before the Assassination Records Review Board stating that the three doctors had not been allowed to conduct a complete autopsy: “Throughout the autopsy, we were told about the wishes of the family to limit the autopsy to the head, and then it was extended to the chest.”

He could not remember who had told them this or on what authority. No wonder he couldn’t remember – apart from the medics, there were 23 others crowded into the autopsy room including air force, army and navy officers and Secret Service members. One man took his own photographs until his camera was confiscated. It was reported that Burkley said at one point: “All we need is the bullet.” At that stage no one knew how many times Kennedy had been hit. Indeed, there were reports of up to six gun shots at Dealey Plaza, later blamed on echoes or ricochet.

Complicating issues and feeding conspiracy theories for years, were memos written by two FBI agents who attended. As the pathologists worked on the corpse, they spoke aloud about their findings, even speculating what might have happened. Later, between themselves, they agreed on what they believed were the facts. The FBI reports of the proceedings included the pathologists’ speculation as fact, feeding endless two-shooter theories.

To say that Kennedy’s brain was clumsily manhandled is an understatement. It reportedly had been removed even before Finck turned up at Bethesda. It was subject to a separate autopsy two days later. Or maybe three. Perhaps more, they couldn’t quite recall. Humes, Boswell and Finck took part with others. But maybe Finck did not. He thought he had. The others thought he hadn’t. Autopsy photographer John Stringer certainly was there but always insisted the photographs in the National Archives were not his, and indeed might be of another brain.

During the weekend after the autopsy, Kennedy’s family, knowing the brain had been removed for examination, wanted it reunited with its owner and placed in the mahogany casket that would then be placed in a copper-lined, 1400kg vault.

Things happened quickly. Kennedy’s funeral was taking place on Monday, November 25. Coincidentally, Oswald and Tippit would also be buried that day.

But that reunion never happened. The brain was later discovered in a stainless steel container in a Secret Service locker and then sent to the National Archives where, in 1966, it was found to be missing. It is confidently reported that Kennedy’s brother Robert had it removed so no researchers in the future could examine it, possibly to discover from what other diseases the president suffered and what medications he was receiving – the truth of which might have been JFK’s greatest secret, including his treatment for Addison’s disease.

But the biggest blunder was made on the evening of November 23 and by the man responsible for overseeing the post-mortem of the victim of one of history’s most notorious assassinations.

The Bethesda autopsy started at 7.30pm. Burkley insisted it be completed overnight. Among the unwieldy throng allowed to witness this, the doctors overheard talk of conspiracies, that the Russians or the Cubans had arranged Kennedy’s death. Humes later described the situation as fevered, even on the edge of hysteria.

It took about 10 hours. Lead pathologist Humes took the notes and wrote a draft autopsy report, then drove home, arriving about 7am. He was exhausted but remembered he was to attend his son’s First Communion in a few hours. Then he had to return to Bethesda to speak to Dallas doctors to compare notes.

Back home that evening he stoked up a fire in his sitting room to ward of the cold. He gathered his notes and the draft report. They were stained by the president’s blood and he briefly felt queasy handling them. Odd, one might think, for a man whose business it was to dissect cadavers.

He said later he decided to transcribe the notes and draft post mortem on to clean sheets of paper, word for word. Why he would do that is a mystery.

He fully understood the importance of those contemporary, original notes and what might be read into his rewriting them. Perhaps he really was put off by the blood.

And, perhaps, as he would later insist, he wanted to prevent them becoming ghoulish collectors’ items, or maybe he felt that in the febrile atmosphere and rushed urgency the previous evening he might have made errors in spelling or medical terminology. After all, he understood clearly that the world would be reading his words in forensic detail.

After he had copied every word to fresh notepads, he gathered together the bloodstained pages, walked over to the fireplace, and, in an act he would regret for the rest of his life, slowly fed them into the flames.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout