Rolling Stones, psychedelics and a pile of bricks

Redlands, the 16th-century Sussex farmhouse owned by Keith Richards, was the real star of the band’s 1967 drugs bust.

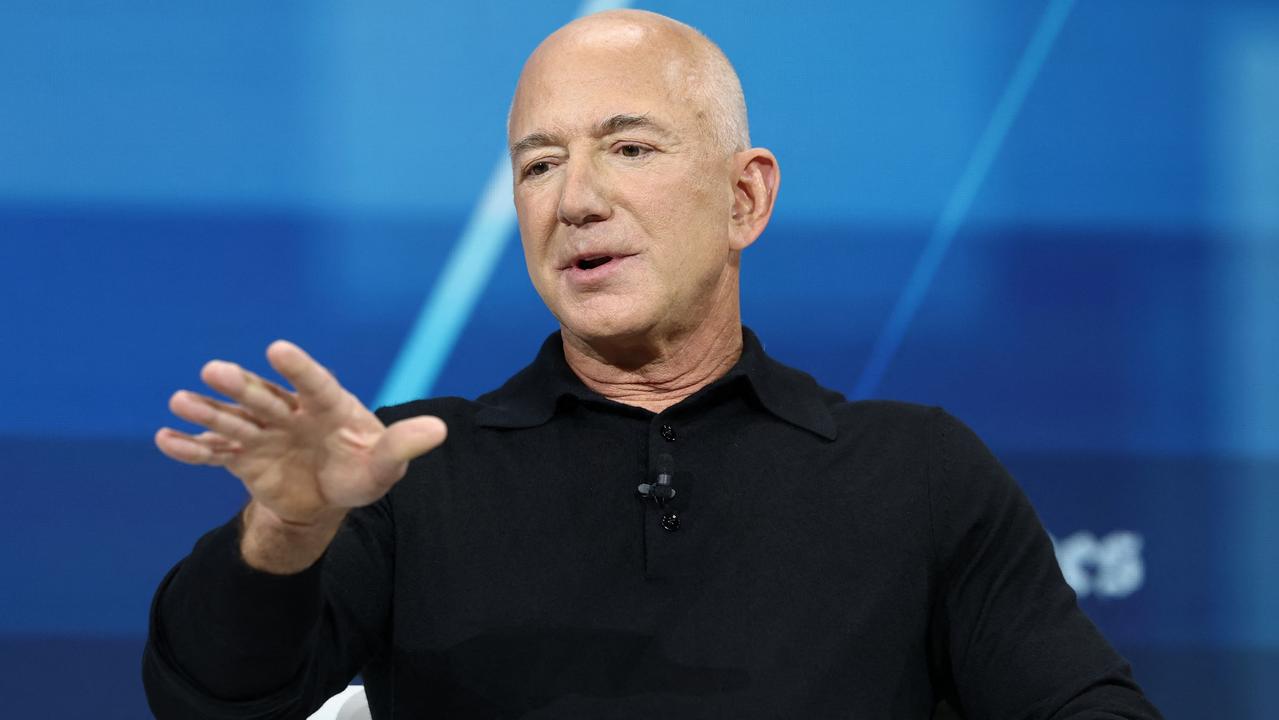

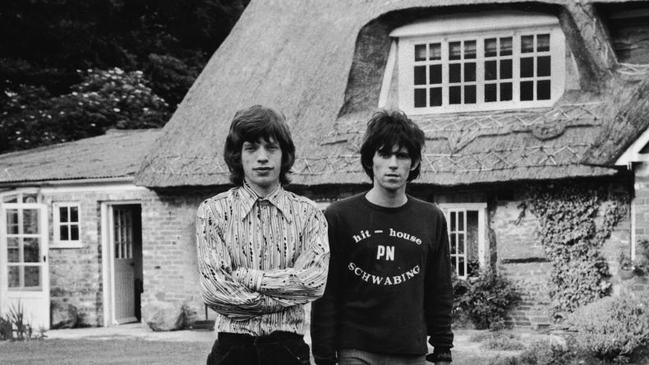

Just before 8 o’clock on the evening of Sunday, February 12, 1967, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were watching television with friends at Redlands, Richards’ farmhouse in West Wittering, Sussex, when they heard a knock at the door.

Groggy from a weekend of drink and drugs, Richards opened up to find “a whole lot of dwarfs” on the doorstep, wearing “dark blue with shiny bits and helmets”. Their leader handed over a piece of paper. “Come on in,” the acid-addled Richards said, and the dwarfs trooped inside. Only then did it dawn on him that, far from being extras from an amateur production of The Hobbit, his visitors were actually members of the West Sussex constabulary.

So began the Redlands affair, a landmark in the cultural history of the 1960s. By the time it was over, the two Rolling Stones, along with their art dealer friend Robert Fraser, had been convicted of varying drug offences and imprisoned for a single evening before their release pending appeal.

This provoked a blistering editorial by The Times’s editor, William Rees-Mogg, entitled “Who Breaks a Butterfly on a Wheel?”, arguing that the judge had unfairly punished the Stones for their celebrity. And although not many newspaper editorials make a difference, this one did. Richards even claimed to have been “saved by Rees-Mogg”, not a phrase you hear often. (The appeal resulted in a non-custodial sentence).

All this was, of course, a long time ago. Yet it clearly has an enduring resonance, since we recently learned that a long-awaited film seems likely to enter production in a few months, with Joseph Fiennes lined up to play the Stones’ barrister, Michael Havers (father of actor Nigel Havers).

Why does this case, apparently so trivial, fascinate people so much? An obvious answer is that it’s simply a very good story. There are the voyeuristic details, such as the constables’ shock at the sight of Jagger’s naked girlfriend, Marianne Faithfull, wrapped in a large fur rug. There’s the unexpected twist, as the fogeyish editor turns out to be the unlikeliest of rock-star allies.

And, most satisfyingly for a historian, there’s the window it offers into the contradictions of the 1960s. We think of the story as a clash between young and old, yet polls found eight out of 10 youngsters thought the original judge was right to send Jagger and Richards to prison. So much, then, for the generation gap.

Yet for me the real star wasn’t Jagger, Richards, the judge or even the editor. It was Redlands, the thatched 16th-century farmhouse Richards bought. And I think the real heart of the story was the social and cultural shift that allowed somebody like Richards, the son of a lightbulb factory foreman, brought up on a Dartford council estate, to buy such a house in the first place.

What took Richards to Redlands? The answer is that he’d made a lot of money and, like so many rock stars, was desperate to get out of the Swinging London goldfish bowl. By his own account, he was driving around Sussex looking for houses, took a wrong turn and fell in love at first sight. The owner, a retired naval commodore, came outside. They got talking and Richards said bluntly: “How much?”

The commodore asked for £17,750. So, according to his autobiography, Richards drove straight back to London, got to the bank just before it closed and took out “20 grand in a brown paper bag”. By evening, he writes, “I was back down at Redlands, in front of the fireplace, and we signed the deal”.

Too good to be true? Perhaps, but it’s a wonderful story. There’s no doubt Richards loved the house: when the Stones’ fan club magazine came to interview him a few months later, he was fairly bursting with pride: “I’m going to have mauve paint in the dining room … I’m knocking down walls and blocking out doors. Downstairs I’m making a small cloakroom for people to hang their coats in.”

To many observers, though, all this was enraging. Ten years earlier, rock stars hadn’t even existed; what were they doing in Britain’s country houses? Even the police remarked again and again on the incongruity, as if unable to comprehend it. “Redlands gave us a bit of a shock,” one admitted. “From the outside it’s a really beautiful house – olde worlde, half-beamed. Then you go inside and it’s decorated in mauve and blacks, all the beams painted like that … It really hurt looking at the inside.”

As for the trial judge, Leslie Block, he made no secret of his view that Jagger and Richards had got above themselves. “We did our best, your fellow countrymen, I, and my fellow magistrates, to cut these Stones down to size,” he told, of all things, the Horsham Ploughing and Agricultural Society, “but, alas, it was not to be, because the Court of Criminal Appeal let them run free.”

As it happened Block, too, lived in a large Tudor farmhouse. But as a former naval commander who had won a Distinguished Service Cross for bravery in World War II, he was the right sort of person – or at least he thought he was. So it’s easy to imagine how he felt, as the Stones passed him on the social ladder.

Yet it was, of course, Richards who prevailed, paving the way for legions of pop and rock stars, footballers and even social media influencers. And in this light, it seems obvious the Redlands affair is less about sex, drugs and rock’n’roll than about that most abiding British national obsession: class. It’s a tale of patricians and parvenus, snobbery and social anxiety – a vintage country house drama, funnier than Brideshead Revisited, richer than Downton Abbey, more poignant than Saltburn. No wonder we love it.

The Times