Real wild child Iggy Pop tempered by time

After a half-century in the industry, the whole rock ’n’ roll scene doesn’t agree with Iggy Pop the way it used to.

As you would hope on meeting him for the first time, Iggy Pop is naked from the waist up. His 72-year-old torso still has a sinewy muscularity and his trousers are so low they seem vaguely obscene. His silvery blond mane of hair is shoulder-length and dead straight, and a wide, boyish grin breaks out whenever something amuses him — and turns into a snarl when it doesn’t.

The man who predated punk by a decade as leader of Detroit garage legends the Stooges, who may well have invented stage-diving, and came up with the immortal line “I’m a streetwalking cheetah with a heart full of napalm” (from Search and Destroy) under a tree in Kensington Gardens in 1972 while smoking Chinese heroin and imagining himself as a Vietnam vet, looks like the living embodiment of rock ’n’ roll. And rock ’n’ roll has proved a harsh mistress.

“It is common knowledge that I’ve been living on one leg for a while,” says Pop. He does indeed have one leg much shorter than the other and walks with a rolling, tilting gait. “I can’t stage-dive now because everything is held together with safety pins. There may be a time when I can’t do rock ’n’ roll gigs any more, which will kill me, but then I came up with some pretty bad osteoarthritis 30 years ago and thought, ‘What the f..k am I gonna do? I can’t even walk across the room.’

“I met this tough little Korean guy who taught me tai chi and qigong and after that I didn’t want to smoke dope, I didn’t want to smoke cigarettes, and I could keep touring. Now I drink like a Frenchman, good wine with dinner at night. I go to bed early. And I live in Miami, which helps.”

He’s a regular sight in the city, cruising in his open-top Rolls-Royce with his third wife, Nina Alu, a statuesque Irish-Nigerian. The land of Versace mansions and blue-rinsed retirees may seem an unlikely home for a hellraiser of Pop’s vintage, but he reveals himself to be more complex than the wild-man persona suggests.

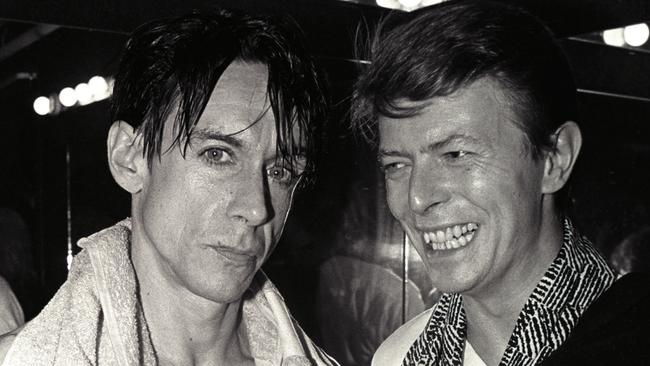

Free, Iggy Pop’s first album since Post Pop Depression in 2016, is a long way from the primitive thud of the Stooges or the tense monochrome art rock of The Idiot and Lust for Life, 1977 solo classics that came out of his time in Berlin with David Bowie. It is a late-night jazz album, recorded with trumpet player Leron Thomas and ambient guitarist Sarah Lipstate, and among its subtle charms is James Bond, a feminist take on the fictional sexist spy, and a sombre reading of Dylan Thomas’s Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night. Pop says the new direction is thanks to hosting his show on BBC Radio 6 Music and discovering a new world of music.

“When you get older, and there is such a cacophony of demands on you just to survive, you don’t want to hear the new shit. You only want to hear whatever reinforces your trip. But then you run out of your old Link Wray records, you have to start listening, and you go, ‘Wow, there’s a lot of stuff out there!’ ”

You also have to wonder if Free is a product of Pop’s age. With the Thomas poem he’s surely making a statement about his mortality.

“It’s more about my dad,” says Pop, who has a son, Eric Benson, born in 1970 after a short relationship with Paulette Benson. “Dad didn’t make a fuss when he went, but he had a rough time at the end. I thought he was a great man. I was a little scared of him, actually.”

Before he became one of the most outrageous of rock stars, Iggy Pop was James Osterberg, the shy, studious child of a high school teacher and a baseball coach who lived in a trailer park on the edge of Ann Arbor, Michigan. His father was adopted, both parents came from midwest families who lost everything in the Depression, and it seems they were supportive and disapproving of their son. They bought him a drum kit — quite a sacrifice for people who lived in a trailer — but when he told them he was giving up college to become a musician his father stood in the doorway of the trailer and told him he would have to push him out of the way first.

“He was a lot bigger than me too,” Pop says. “When the Stooges developed they never said anything against me, although they came to a large show at the state fairground once and my dad said, ‘Son, you remind me of those young athletes on the school team — a lot of flash, but no control.’ ”

It might have been worse if Dad knew the whole story. Living communally in a decrepit Ann Arbor pad they called the Funhouse, also the name of their free-jazz tinged second album from 1970, the Stooges made a name for themselves on the Michigan scene as the most degenerate band of them all. With teenage malcontents Ron and Scott Asheton on guitar and drums they had a punk attitude that stood in marked contrast to the hippie spirit of the times. Songs were made up of little more than a brutal riff and a few words on cheap thrills and boredom. Pop developed a stage routine that featured exposing himself, rolling in broken glass and generally causing as much offence as possible.

“My dream audience were the stoner kids,” he says. “I was thinking about that kid in 10th grade who doesn’t like all this shit being peddled to him by the record companies. I was obsessed with being ahead of everyone else while doing simple, hard-hitting music that had enough form to be relatable.”

The first two Stooges albums bombed and the band split up. One of the few who had been taking notice was Bowie, and after hooking up in New York with James Williamson, a virtuoso guitarist with a uniquely aggressive playing style, Pop accepted an invitation from Bowie to relocate to London in 1972 and record what would become the Stooges’ masterpiece, Raw Power.

“David Bowie and James Williamson were heads and tails of the same coin,” Pop says. “One was more aggressive in reaching for an audience, the other was more aggressive in general, and I gravitated towards them because once I decided to be a musician for life I accepted that nothing about me was commercial. I didn’t like hit records and I still don’t. They had to drag me screaming toward (the cheesy 1986 smash) Real Wild Child. I’m not exactly Adele. All I could do was create something wilder and heavier and greater than what was already out there.”

On arriving at Heathrow, Pop and Williamson were deemed so undesirable that Customs officials wanted to send them straight back to the US. It was only after Bowie’s manager Tony Defries intervened that they were allowed to stay. Not that it endeared Pop to his new boss.

“He didn’t want me bringing Williamson to England, and when an English prick thinks he’s being cold he goes, ‘Oh, so there are two of you now?’ ” Pop says, affecting a tart, fey voice. “Here’s this guy with a silly hairdo and a big cigar who thinks he’s Colonel Tom Parker, who puts us in the Portobello Hotel and hooks us up with all these terribly outrageous English characters. I tried to be polite, but Williamson wouldn’t have anything to do with them.

“And we Americans have inferior culture but superior plumbing, so neither of us had ever seen anything like the box on the wall in the bathroom that you had to turn on to get hot water. For weeks we thought the English only had cold showers.”

Convinced that all English musicians were effete poseurs, Pop and Williamson insisted on bringing the Asheton brothers to London for Raw Power. Bowie’s management team got revenge in their own way.

“Williamson and I asked to be moved to the Kensington Gardens Hotel because we liked hanging out at Kensington market, so they put us together in the bridal suite,” Pop says. “When the Ashetons came over we moved into a crappy basement off Fulham High Street and David would drop by. One day we went to a place nearby called the Baghdad House, where they put hashish in your falafel, and he said, ‘Do you want me to produce this album?’ I said, ‘No thanks’.”

Bowie produced the album anyway. “I told them I couldn’t write lyrics in the flat because the Stooges didn’t respect writing, so they rented me a room at Blakes (hotel) and that’s where I met a lot of attractive people with drug problems. I fell into a certain routine, but I got the job done.”

If London was bad, Los Angeles was worse. In 1973 Defries decided the band had a chance of making it there; Pop found a girlfriend in teenage groupie Sable Starr and went from dabbling with heroin into full-blown addiction.

“That was not the right place for us,” he says with a sigh. “It was full of dud, petty bourgeois Americans pantomiming as counterculture characters — ‘I’m the guru, I’m the health food nut, I’m the love machine’, just horrible. And on the street you had something altogether nastier, which was drugs, guns and hoes. It was not a good period.”

Before Pop ended up homeless and checking into a mental hospital to beat drug addiction, there was the release party for Raw Power to get through. It was held at the top of the Hyatt House hotel on Sunset Strip, and he decided to decorate the room with little plastic turds and splatters of vomit. “I was a little deranged at the time,” he admits. “Robert Plant turned up and he was a decent fellow, but generally nobody wanted anything to do with us. By that point the drugs had got nastier and the only people we were hanging out with were the ones with the drugs.”

Help came, again, from Bowie. He suggested they relocate to Berlin and later turned one of Pop’s songs, the atypically gentle China Girl, into a massive hit. “That was a much quieter period, more focused,” Pop says of the Berlin-Bowie years.

Pop’s relationship with Bowie was complex. Clearly there was mutual love and respect, with Bowie writing The Jean Genie about Pop and Pop describing his friendship with Bowie as “the light of my life” on the latter’s death in 2016. But you suspect Pop resented Bowie for taking their collaboration and running with it — as he did with everyone he worked with. Perhaps Bowie put it best when he said in 1999: “Jim had come to resent the fact that he couldn’t do a f..king interview without my name being mentioned.”

From then until now, Pop’s life and career have been an unlikely exercise in survival. He’s a household name that few households could sing a song by, except for perhaps Lust for Life after its inclusion in the film Trainspotting in 1996. Even after the success of a Stooges reunion in 2003, leading to belated glory for an initially unsuccessful band second only to the Velvet Underground in terms of influence, he still seems like an outsider. “I’m not a particularly happy person in rock ’n’ roll. The music is great but the scene is pretty hard-bitten, dude. I could have been a wiser bandleader, but then I was an artist. And a rock kid. And a little trashy.”

At the end of Post Pop Depression, which Pop hinted would be his last, comes a song called Paraguay, on which he announces plans to disappear into the jungle of the South American country. Instead he’s still making records, still on the road, doing five-hour exercise routines to get through his febrile live performances. But the gigs are getting fewer and further between. You wonder how much longer he can keep going — and how many more years there are in rock ’n’ roll itself.

“Rock music can only carry on in the context of other, related cultural activities. Women have come forward and some of the rock girls are getting support from the big fashion houses,” he says, thinking of the punk bands Amyl and the Sniffers and Surfbort modelling for Gucci. “But it won’t ever again reach the ridiculous pinnacle of big lights! Big stadium! Big music! For rock — that’s gone. All that is for the hippety-hops. It is their time now.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout