Rape is the oldest weapon of war - and it’s still being wielded today. We must give a voice to the victims

Whether in Afghanistan, Iraq, Ukraine or the Hamas outrage on October 7, for too long the world has turned a blind eye to sexual violence in war. We must give a voice to the victims.

Imagine for a moment your beautiful 20-something daughter, sister or friend was now in their tenth week of Hamas captivity in Gaza. Instead of heading off travelling with the money she had saved from waitressing as planned, she is living in terror.

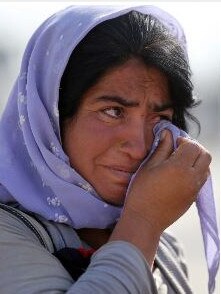

Not only would you be tearing your hair out about her survival, but at what her captors might be doing to her. “It’s a constant thought in my head,” one mother, whose daughter was abducted from the Supernova music festival, told me last weekend in Tel Aviv. “We know [sexual violence] is common for women in captivity - that’s why we must get them out.”

She told me she was trying not to think about it. After the hostage releases had been halted, her daughter and 19 other women and girls were still being held. “Is it why they didn’t release them?”

We hugged as mothers for we both knew what she is referring to. I kept thinking about her as the graphic accounts of sexual violence I reported on in The Sunday Times last weekend reverberated around the globe, and as some freed hostages apparently shared testimonies of being sexually abused in captivity.

When my book on war rape came out in 2020, I noted at the end; “I don’t think I will ever finish this journey - it seems to be happening more and more.” I had no idea then that, within three years, we would have two major wars, in Europe and the Middle East, both of which would see rape used as a weapon. In Iran, many women thrown into detention centres for removing their hijabs during the uprisings that took place after 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died in the custody of morality police, have also reported being raped. I have spoken to Iranian doctors who were so troubled by the injuries of the young women they treated that that they risked imprisonment themselves by smuggling out material.

Each time, as reports emerged, I felt a dread sense of Not Again. Rape is one of the oldest weapons of war but I didn’t want to believe that something described in Homer’s Iliad as happening to the women of Troy is still happening in the 2020s.

I also knew that voices of women in war have for far too long been silenced. As a female war correspondent I have spent my entire 35-year career trying to get them heard, whether it’s in Afghanistan, Iraq, South Sudan or Zimbabwe.

In areas of Ukraine around Kyiv that had been under Russian occupation, I heard story after story to make you weep - the sisters kept in captivity by soldiers, the elder forced to watch them rape the younger, begging them to take her instead, until her sibling eventually died; the haunted blue eyes of Vika who had been taken as “entertainment” by a soldier the age of her son.

I know too how hard it is for victims to come forward. Rape is the one crime where the victim is often made to feel they have done something wrong.

Researching my book, I met grandmothers in the Philippines who took 50 years to come forward about being held as “comfort women” by Japanese soldiers, and had never told their families from shame. In Bosnia some survivors are only coming forward now, 30 years on from the war.

When I gave book talks in Germany and Poland, people told me: “This happened to my grandmother/aunt and no one ever spoke about it.” In Germany, at the end of the Second World War some committed suicide rather than live with how Red Army soldiers had brutalised them.

To me the most heartbreaking aspect in my reporting has been seeing young girls like the Chibok Girls and other Nigerians taken as “bush wives” by Boko Haram fighters then released, ostracised by their own families and communities who saw them as “sullied”.

Even in Ukraine, where for the first time there was widespread reporting of the issue, women told me they wouldn’t report because they feared being judged and don’t believe it will make a difference. Just look at the shameful rate of conviction in this country, where last year almost 200 women a day reported rape, of whom around 1 per cent will see a charge.

The Israeli women activists pointed out that hospitals struggling to deal with the mass calamity of October 7 had not even thought to ask survivors about sexual abuse.

These women were angry - not just at what Hamas had done to the women, but at how the rest of the world had seemingly turned a blind eye to the sexual violence committed on October 7.

Why was no one listening to them, they wanted to know. I pointed out that, in the first three months of this year more than 31,000 cases of sexual violence were reported in IDP (internally displaced people) camps in the Democratic Republic of Congo, yet you would be hard pressed to find a line in the media.

I couldn’t explain why UN Women or the UN special representative on sexual violence had not answered their letters - nor why it took the former 57 days to make a statement, while the special representative expressed only her “grave concern” on Friday - after 62 days.

Yet, speaking to the first responders and mortuary workers, it was clear from their descriptions of the women’s bodies what had happened to them before they were murdered. There were also witnesses, deeply traumatised by what they had seen.

After I wrote about it many women, and men, thanked me. But others accused me of Zionist propaganda. They also accused me of not including what Israelis are doing to Palestinian women - though I have also written about allegations of abuse in Israeli prisons.

I pointed out I have written about rape all over the world perpetrated on or by Christians, Muslims and Buddhists for this is a crime that has no religion or ethnicity. Yet, I don’t remember when I reported on rape of Ukrainian women being asked why we were not reporting on what Ukrainians were doing to Russians.

Is it not possible to be absolutely horrified by what’s happening in Gaza, where according to ActionAid three women an hour are now being killed, as well as being horrified by what happened to Israeli women? Can’t we instead work together to tackle the real problem which is impunity and shameful inaction? For even when there is global outrage, accountability remains the exception not the rule.

The first prosecution of rape as a war crime did not occur until 1998. Despite that landmark ruling by the International Criminal Tribunal on Rwanda, after the brave testimony of five women and the intervention of a female judge, it can still take decades for perpetrators to be brought to justice. In most cases they never are.

The International Criminal Court has only convicted two people for sexual crimes in its 22 years of existence. Even in Bosnia where world leaders vowed “never again”, the international tribunal, part of the UN security council, convicted only 36 men for sexual crimes. Women there tell me they see their perpetrators in coffee shops - or even still in the police.

No one has been prosecuted for the rape of thousands of Rohingya women by Burmese soldiers or for what Boko Haram did to thousands of Nigerian girls and women. And just one for what happened to the thousands of Yazidi women taken as sex slaves by Isis - an Iraqi prosecuted in Germany, which is leading the way by using universal jurisdiction. That means any war crime can be prosecuted in any country, not necessarily where it took place.

Next year will be ten years since Islamic State fighters entered Yazidi villages and took thousands of girls as sex-slaves. Most are still in camps, unable to go home, forgotten by the world that once made headlines about them.

It was a WhatsApp message from one asking me, “We told our stories but what difference did it make?” that set me on the path for writing my book. And I really don’t want to keep adding to it.

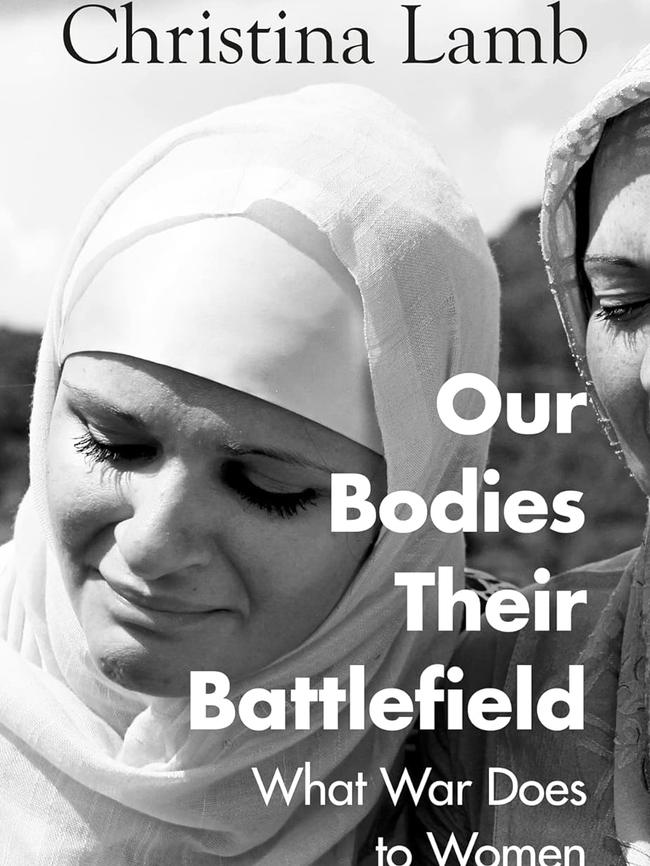

Christina Lamb is the author of Our Bodies Their Battlefields; What War does to Women

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout