Queen Elizabeth 1926–2022: A long life dedicated to her people

The prestigious UK masthead says the reign of Britain’s longest-serving monarch was defined by an unwavering sense of commitment to her country and her subjects of the commonwealth.

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II: Born April 21, 1926, Died September 8, 2022, aged 96.

When the Queen became this country’s longest-serving monarch, the humility with which she acknowledged the passing of that historic moment reflected the same selfless dedication with which she once promised to serve her people. Some 68 years separated the pledge she made in Cape Town on her 21st birthday and the modest speech that she made on passing Queen Victoria’s record in September 2015; but even if the empire to which she devoted herself no longer exists, the values she spoke of then were the values to which she still held true a lifetime later. “My whole life,” she said, in that resonant passage that captured imaginations worldwide in 1947, “whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service.”

It was, in the event, a long life, one that both straddled history and made history. Born at the time of the General Strike, she acceded to the throne at a time when members of the royal family were still treated with a reverence that seems alien today. By the time she died, she had lived through an era of vast social, material and technological change, from a period when few people had television sets to the age of the internet.

She was a symbol; but what she symbolised changed over the years. At the beginning of her reign, her youth and beauty – set against the austerity and uncertainty of the post-war years – were seized on as an emblem of hope, a harbinger of a new Elizabethan age. If along the way she was regarded by some as a totem of all that was wrong with a class-ridden society, by her later years she came to stand for those old-fashioned virtues that are in such short supply these days: service, duty, modesty, self-sacrifice and hard work.

Yet it is important to remember that beneath the crown there was also a woman, a wife, a mother. She had to cope with the early death of her father and, later, the indignity of unsparing public scrutiny as the marriages of three of her children collapsed. Too frequently the human side of her character – her talent for mimicry, her sense of fun, the way she came to life when she was watching her racehorses in action – was overlooked as a nation concentrated instead on the cipher it wanted to see. That oversight may have been partly her own work, as she spent her life presenting a public image suitable for the head of state. However, it was one of the many remarkable aspects of her that, unlike most, she became more relaxed and open to new suggestions as she grew older: who would have believed that the Queen we once knew would have agreed to take part in a stunt with James Bond for the opening of the London 2012 Olympics?

Above all, she was the woman who saved the monarchy in this country. That is not to say that without her we would have had a republic by now, or that the monarchy did not endure some troubled times during her reign when the unpopularity of some of its members led critics to question its very future; but it is thanks to her dedication and seriousness of purpose that an institution that has at times seemed outdated and out of keeping with the values of contemporary society still has a relevance and popularity today. She made a promise in Cape Town, and she was as good as her word.

The future Queen Elizabeth II was born in the early hours of April 21, 1926. She was the daughter of the Duchess of York, the25-year-old wife of George V’s second son, Albert. The birth took place at 17 Bruton Street, Mayfair, the home of her mother’s parents, the Earl and Countess of Strathmore. It was a difficult delivery: the official bulletin referred to medical complications and “a certain line of treatment”, a circumlocution which the newspapers of the day declined to translate: she was delivered, in other words, by caesarean section.

Although Elizabeth was not born to be Queen – at that time, long before anyone had heard of Wallis Simpson, Albert’s elder brother, David, was the heir to the throne and few saw any reason to doubt that the future Edward VIII would do his duty by providing the next generation of the royal family – her arrival prompted great excitement. Crowds gathered outside the house and the Daily Sketch, with perhaps less faith in the Prince of Wales than others, announced: “A possible Queen of England was born yesterday.”

Among the first visitors to see the new baby, named Elizabeth Alexandra Mary after her mother, great-grandmother and grandmother respectively, were the King and Queen. “Such a relief,” wrote Queen Mary in her diary, noting that Elizabeth was “a little darling with lovely complexion & pretty fair hair”.

In the ordered, upper-class existence of her parents, Elizabeth’s world was the nursery, which was ruled over by the formidable Clara Knight, who was known to her young charges as “Allah”. The distance between child and parent, commonplace in aristocratic families of the time, was exacerbated by her parents’ royal duties. When Elizabeth was nine months old, the Duke and Duchess of York went on a tour of Australia and New Zealand that took them away for six months. “It quite broke me up,” her mother wrote in her diary, recalling their parting. “The baby was so sweet, playing with the buttons on Bertie’s uniform.”

To judge by contemporary reports, she was a solemn, self-contained child. Winston Churchill met her when he was invited to Balmoral in the autumn of 1928. “[She] is a character,” the chancellor wrote to his wife, Clementine. “She had an air of authority and reflectiveness astonishing in an infant.”

With her parents so often away, Elizabeth saw much of her grandparents, an arrangement that delighted them. During a three-month stay at Buckingham Palace, she would be brought down for tea every day with the King and Queen. “Here comes the Bambino!” the normally stiff Queen would declare. According to some reports, the King used to play with his granddaughter in a way that he never did with his own children: he called her Lilibet, in imitation of her attempts to say her name. Her family called her Lilibet ever after. At Sandringham the King liked to have her sit next to him at breakfast and would take her round the Royal Stud to show her his favourite horses: it is more than likely that Elizabeth inherited her lifelong passion for horses from her grandfather, who gave the child her first pony, a shetland called Peggy, for her fourth birthday.

Outside the confines of palace life she was a celebrity. At the age of three, she was on the cover of Time magazine, an appearance that was credited with prompting a fashion for children being dressed in yellow instead of pink or blue after it was revealed that yellow was the predominant colour in both the royal nursery and Elizabeth’s wardrobe. By the time she was four, and had a younger sister in the form of Margaret Rose, born at Glamis Castle, she had her own waxwork at Madame Tussauds – riding a pony (the second Tussauds waxwork to be made of her) – and a large slice of Antarctica had been named after her.

Even her father seemed swept up in the enthusiasm for the much-lauded young princess. Perhaps, he hinted one day in the early 1930s to the poet Osbert Sitwell, she was born for higher things. Comparing her to Queen Victoria, he gave Sitwell a meaningful look and said: “From the first moment of talking she showed so much character, that it was impossible not to wonder whether history would not repeat itself.”

As the girls grew up the Yorks – by now living at 145 Piccadilly, a large townhouse overlooking Green Park – came to be held in the popular imagination as a model family. They were royal, but sufficiently removed from the ceremonial of court life to represent an ideal to which Middle England could aspire. As Ben Pimlott, the historian, wrote, with the reserved, proud father, practical, child-centred mother, and well-groomed, well-mannered children, they were “a distillation of British wholesomeness”.

For that contented family unit, happy with their place in the order of things – “us four”, as Bertie called them – everything was to change in 1936. George V died on January 20, his end signalled by the famous medical bulletin from his doctor, Lord Dawson of Penn: “The King’s life is moving peacefully towards its close.” When his body was brought to lie in state in Westminster Hall, the nine-year-old Princess Elizabeth was allowed to stay up late to stand in front of the coffin as her father and three uncles stood at each corner.

The Abdication crisis that followed, when Edward VIII decided that he could not continue as king if he could not marry the twice-divorced Mrs Simpson, had such a devastating impact on the royal family that its repercussions are still felt today. It was suffered most immediately by Bertie, who did not want to be king, was rendered thoroughly miserable as the drama unfolded, and implored his elder brother to stay. When the decision was finally made Bertie, appalled by the burden facing him, broke down in tears on his mother’s shoulder.

Elizabeth was now next in line to the throne. “When our father became King,” Princess Margaret recalled, “I said to her, ‘Does that mean you’re going to become Queen?’ She replied, ‘Yes, I suppose it does.’ She didn’t mention it again.” According to her governess, Marion Crawford – “Crawfie” – Elizabeth was horrified to learn that they were to move to Buckingham Palace: “What – you mean for ever?”

Her father’s Coronation was on May 12, 1937, the day that had been reserved for the Coronation of Edward VIII. In a diary written in the neat, rounded hand of the 11-year-old Elizabeth, she recorded all that happened that day, from the moment she leapt out of bed at 5am and crouched at the window with her nursemaid Margaret MacDonald – “Bobo” – looking at the crowds taking their places in the stands below, to the formal photographs at the end of the day, “in front of those awful lights”. Westminster Abbey, she said, was “very, very wonderful”. She wrote: “The arches and beams at the top were covered with a sort of haze of wonder as Papa was crowned, at least I thought so.”

Elizabeth and Margaret were the last generation of the British royal family to be educated at home. There were French lessons with Antoinette de Bellaigue, dancing with Miss Vacani, drawing sessions and twice-weekly riding lessons; and, for Elizabeth, history with Sir Henry Marten, vice-provost of Eton. He was an eccentric figure who secreted lumps of sugar in his pocket that he would munch at intervals; he also kept a raven in his study, which occasionally nipped his ear. He taught the princess not only about the kings and queens of England and Britain, but also the very fundamentals of constitutional history – the building blocks of how one day she would reign as Queen. The constitutional textbooks, which are kept under lock and key in the College Library at Eton, are marked throughout with Elizabeth’s painstaking annotations, a premonition of the punctilious constitutional monarch who would later be such a diligent reader of her government red boxes.

Her parents did what they felt they could to allow Elizabeth to mix with other girls of her age, to feel that she was part of the world outside palace walls. The 1st Buckingham Palace Guide Company was formed (with a brownie pack for Margaret, who was too young to be a guide) as a substitute for the princesses going out to school, although as a social leveller it was of limited value. As one member recalled: “They were all dukes’ daughters and Mountbattens – it wasn’t at all democratic.” The other girls, who turned up for the first meeting in their best party frocks and white gloves, with nannies and governesses in tow, were expected to curtsy to the princesses.

While Elizabeth enjoyed the fun and games of the guides – the team games, the expeditions, the camp fires – she was, in contrast with her sister Margaret, the shy, serious one. Margaret was naughty, high-spirited, amusing and dreadfully spoilt; whenever they had company Margaret would soak up all the attention, a state of affairs that Elizabeth was only too happy to encourage. “Oh, it’s so much easier when Margaret’s there,” she would say. “Everybody laughs at what Margaret says.”

Her natural reserve, however, did not prevent her from noticing the handsome young cadet who spent the afternoon with them during a visit to the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, in July 1939. Elizabeth was 13.

There was an outbreak of mumps and chickenpox at the college, and it was thought inadvisable for the two princesses to attend chapel with their parents. Cadet Captain Prince Philip of Greece was 18 and was asked by his uncle, Lord Louis Mountbatten – “Uncle Dickie” – who was part of the royal party, to entertain the princesses. Philip, who had led a peripatetic existence since his family had been exiled from Greece, was not a wholly unknown quantity. He was, like Elizabeth, a great-great-grandchild of Queen Victoria and he had known the British royal family since he was a child, when he took tea at Buckingham Palace with Queen Mary. She reported him as being “a nice little boy with very blue eyes”.

Sketchy accounts, and a couple of photographs, remain of what happened that afternoon. Philip joined the girls when they were playing with a children’s train set; later they amused themselves by jumping over tennis nets and playing croquet. Crawfie, not necessarily the most reliable of witnesses, recalled: “I thought he showed off a good deal, but the little girls were much impressed. Lilibet said, ‘How good he is, Crawfie. How high he can jump.’ She never took her eyes off him the whole time. He was quite polite to her, but did not pay her any special attention. He spent of lot of time teasing ‘plump little Margaret’.”

Their Dartmouth encounter may not have been the first time they met; other accounts have them meeting at a wedding when he was fourteen and she was nine, and they may also have come across each other at the Coronation of George VI. And the 18-year-old Philip – good-looking, but offhand, according to Crawfie – was hardly likely to have been instantly smitten by a 13-year-old schoolgirl. There seems little doubt, however, that for Elizabeth it was a pivotal moment. Sir John Wheeler-Bennett, in his official biography of George VI – a work commissioned, scrutinised and approved by the Queen – recorded unequivocally: “This was the man with whom Princess Elizabeth had been in love from their first meeting.”

The seeds of love may have been sown, but serious courtship was still a long way off; the start of war saw to that.

While Philip was serving with the Royal Navy, Elizabeth made her own contribution to the war effort in October 1940 when, aged 14, she made a radio broadcast as part of a series called Children in Wartime. Aimed, in the first instance, at the US and Canada, it was addressed to children, but designed to pull their parents’ heartstrings. “My sister Margaret Rose and I feel so much for you, as we know from experience what it means to be away from those we love most of all,” she said in her clear, high voice. The ending was unashamedly corny. “My sister is by my side,” she said, “and we are both going to say goodnight to you. Come on, Margaret.”

“Goodnight,” piped up an even higher voice. “Goodnight and good luck to you all.”

Jock Colville, Churchill’s private secretary, was embarrassed by the “sloppy sentiment” of it all, but his view hardly mattered: the broadcast was a propaganda triumph and the BBC turned it into a best-selling record.

Philip, meanwhile, was having a good war. He saw action in the Mediterranean and was mentioned in dispatches for his role in the Battle of Cape Matapan against the Italian fleet. He found time to write to Elizabeth, however, and she kept his picture on the mantelpiece. In 1943 he was invited to spend Christmas with the royal family at Windsor Castle, where he watched the annual Windsor family pantomime. “After dinner, and some charades,” Sir Alan Lascelles, the King’s private secretary, wrote in his diary for Boxing Day, “they rolled back the carpet in the crimson drawing room, turned on the gramophone, and frisked and capered away till near 1am.” Crawfie observed: “I have never known Lilibet more animated. There was a sparkle about her none of us had ever seen before.”

As the war drew on, and Elizabeth turned 18, she grew increasingly frustrated. Safely sequestered away at Windsor, her social life consisted mainly of enjoying the company of a group of carefully selected young Guards officers, but she was scarcely mixing with a broad range of her contemporaries. All too aware of how her friends were engaged in some kind of war work, she longed to get out and “do her bit”.

Finally, in spring 1945, her father allowed her to join the Auxiliary Territorial Service and take a vehicle maintenance course at Aldershot. It was only a three-week course and, instead of sleeping with the other young women in their huts, she was whisked back to Windsor every night. However, she enjoyed the chatty cups of tea with the other girls and learnt how to service an army truck; and, however brief her stint in the ATS – just a few months – it gave her a brief taste of freedom and a uniform.

That uniform proved its worth on the night of VE Day (May 8), when Elizabeth and Margaret slipped out of Buckingham Palace with their young Guards officer friends. They walked to the Ritz and back past Hyde Park Corner before joining the crowds outside the palace where everyone was shouting: “We want the King, we want the King.” One of the group, Henry Porchester, recalled: “At last they came out on the balcony and we were mixed up in the crowd, no one noticed, no one recognised Princess Elizabeth or Princess Margaret.”

By then Philip was already being considered as a serious suitor. In 1944 his uncle, Prince George of Greece, had made a direct approach to George VI, who said that while he liked Philip, he thought Elizabeth was too young. The Queen was not too sure, either, and a list of suitable young men was drawn up. Philip persisted, while Elizabeth had already made up her mind. When he proposed to her at Balmoral in the summer of 1946 she immediately set about trying to win her father round. It did not take her long, because the King had already been addressing some of the issues raised by the potential match, such as how Prince Philip of Greece should become a British subject. An accommodation was soon reached: the couple could become engaged, but it had to remain a secret until after the family’s royal tour of South Africa the following spring.

For a woman who was to become the most travelled monarch in history, the sea voyage to Cape Town was the first time she had set foot outside Britain. Once there, Lascelles thought she did well: businesslike, but with a good, healthy sense of fun. “Moreover,” he wrote, “when necessary she can take on the old bores with much of her mother’s skill, and never spares herself in that exhausting part of royal duty.” On her 21st birthday, which fell towards the end of the tour, she made the radio broadcast to the empire and the Commonwealth in which she made a dedication that not only captured the imagination of all who heard it, but has come to serve as a distillation of the sense of service and duty that would become such a consistent theme of her reign. “I declare before you all,” she said, “that my whole life, whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service and the service of our great imperial family to which we all belong.”

The empire would soon be no more, but her devotion to duty – which was a response, in part, to the lesson of the Abdication, in which Edward VIII’s personal feelings were allowed to override his royal responsibilities – would help to ensure the survival of the Commonwealth in the decades that followed.

Back home, all was set for a royal wedding. Philip had become naturalised – he was now Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten, RN – and in July 1947 their engagement was announced by Buckingham Palace. The King and Queen were delighted; the palace courtiers, less so. Stuffy, snobbish and deeply antipathetic to this rather disrespectful upstart, they would have preferred Elizabeth to have married someone who would have merged more easily into court circles, some English duke rather than a penniless foreign prince. As Lascelles told a friend: “They felt he was rough, ill-mannered, uneducated and would probably not be faithful.” In the words of John Brabourne, who was married to Philip’s cousin Patricia Mountbatten: “They were absolutely bloody to him. They didn’t like him, they didn’t trust him, and it showed.”

Churchill, on the other hand, thought that the wedding provided just the touch of romance that the country needed as it struggled through the bleak post-war years, describing it as “a flash of colour on the hard road we have to travel”. If glamour and romance were what was required, that was what the Palace was going to provide. Norman Hartnell, the royal dressmaker, designed a dress fit for a fairytale princess, of ivory silk decorated with pearls arranged as roses of York, entwined with ears of corn embroidered in crystal. He liked to tell the story of how his manager was stopped at Customs after a buying trip to the US and was asked if he had anything to declare. “Yes,” he said, “ten thousand pearls for the wedding dress of Princess Elizabeth.”

Wedding presents came from all over the world, from the magnificent – a thoroughbred filly from the Aga Khan and a hunting lodge from the people of Kenya – to the comical, a turkey sent by a woman in Brooklyn, because “they have nothing to eat in England”. Mahatma Gandhi, at Mountbatten’s suggestion, gave a woven cotton tray-cloth that he had made himself and which Queen Mary – no friend of the Indian independence leader – chose to believe was a loincloth. “Such an indelicate gift … what a horrible thing,” she said.

Although anti-German feeling meant that none of Philip’s three sisters, all of whom had German husbands, was invited, the occasion was notable for attracting a splendid array of European royalty. They were entertained in style, with a succession of dinners and parties at St James’s Palace and Buckingham Palace. “An Indian rajah became uncontrollably drunk,” recorded Colville, “and assaulted the Duke of Devonshire (who was sober).” The King led a riotous conga through the corridors of Buckingham Palace, during which a tiara belonging to Princess Juliana of the Netherlands fell off and had to be stuck back on again. Just before the wedding Philip was granted the style of His Royal Highness and the title Duke of Edinburgh.

On the morning of the wedding – November 20, 1947 – it took Hartnell and his team an hour and ten minutes to fit the dress and 15ft train. However, for all the meticulous planning there were still the traditional last-minute panics that enliven any wedding: the tiara given to Queen Elizabeth by Queen Mary, and now lent to the young bride, snapped and had to be repaired. A further crisis ensued when the princess realised that the double strand of pearls that her parents had given her as a wedding present were half a mile away at St James’s Palace with the other gifts. Colville, newly appointed as her private secretary, was dispatched to get them by commandeering the nearest car. Throwing open the door of a royal Daimler, he shouted “To St James’s Palace!” to the chauffeur, only to be confronted by an elderly figure, resplendent with orders and decorations, getting out. “You seem to be in a hurry, young man,” said King Haakon VII of Norway. “By all means have my car, but do let me get out first.”

Inside the abbey, the Archbishop of York told the congregation of 2,000 – the men in uniforms and morning suits, the women in full-length dresses with long white gloves and tiaras – that the service was “in all essentials exactly the same as it would have been for any cottager who might be married this afternoon in some small country church in a remote village in the Dales”. Arguable, perhaps, but in one respect at least it was like any other wedding; during the signing of the register the King and Queen were so moved that they were close to tears. As the King told the archbishop: “It is a far more moving thing to give your daughter away than to be married yourself.”

After the wedding breakfast the couple were pelted with rose petals by the family as they set off in an open carriage to Waterloo Station. Susan, the princess’s favourite corgi, travelled with them, snuggled under a blanket; on arriving at Waterloo she stole the show by tumbling out first in a shower of rose petals.

They began their honeymoon at Broadlands, the Mountbattens’ Hampshire home, where the phone rang off the hook and royal enthusiasts and newspaper photographers laid siege to the house. There was more peace at Birkhall on the Balmoral estate, where they spent the second half of their honeymoon, warmed by log fires and surrounded by deep snow.

The months and years that followed were good times. When they returned from Scotland, Colville noted in his diary: “She was looking very happy, and, as a result of three weeks of matrimony, suddenly a woman instead of a girl. He also seemed happy, but a shade querulous, which is, I think, in his character.”

As a couple they seemed compatible on every level. Sarah Bradford, whose biography of the Queen is arguably the most authoritative portrait of her life, wrote: “Elizabeth was physically passionate and very much in love with her husband.” Even if Philip tended more to coolness than passion, he loved and – crucially – respected her.

Yet while unimpeachably supportive and attentive, he was also a domineering figure. In the early days of their marriage, before she had the authority of the sovereign and before she had learnt how to deal with his overbearing ways, they had their moments. He had no compunction about publicly telling the future Queen not to be “such a bloody fool”. Once, while driving with Lord Mountbatten, Philip was going even faster than usual, causing Elizabeth to draw in her breath. “Do that once more,” he told her, “and I’ll put you out!” When they arrived, Mountbatten asked her why she had not told Philip that he was driving too fast. “But didn’t you hear him?” she said. “He said he’d put me out.”

Three months after the wedding she became pregnant. They had been due to move into Sunninghill Park, next to Windsor Great Park, but that burnt down before they could do so and instead they rented a relatively modest country house, Windlesham Moor, in Surrey. Clarence House, their London home, was in desperate need of refurbishment and they stayed first in Kensington Palace, then Buckingham Palace, before finally moving into Clarence House 18 months after the wedding.

A visit to Paris in the late spring of 1948, her first foreign tour as a newly married princess, was a huge success. The French were struck by her beauty and the quality of her accent, but the warmth of the welcome had its basis in a more fundamental appeal: with her fresh-faced allure, her handsome Viking-looking husband and, once it became publicly known, her forthcoming baby, she was increasingly being seen as a symbol of new era, a beacon of hope as Britain and the rest of Europe emerged all too slowly from the austerity of the aftermath of war.

Behind palace walls small revolutions were taking place too. George VI at first insisted that the home secretary should be present at his grandchild’s birth, just as his predecessor had been there for the princess’s arrival 22 years earlier. Some courtiers thought it was time to do away with this ancient custom, but the King demurred until it was pointed out that all the dominions should also have the right to have representatives present, meaning that there might be seven ministers hanging around in the corridor outside her bedroom. He backed down and the Palace announced that it was ending an “archaic custom”.

Prince Charles was born in the evening of November 14, 1948; Prince Philip, who was playing squash with Mike Parker, his old Australian shipmate from the war who was now his private secretary, had to be fetched to come and see his new child. Elizabeth was enchanted with her son – she liked his hands in particular, “fine, with long fingers” – but it was not long before mother and child had the first of many separations. First it was illness – she caught measles and it was thought best that they should be apart – then Malta. Philip had been posted to the Mediterranean fleet in the autumn of 1949 and she went to join him, leaving Charles to spend his second Christmas with his grandparents at Sandringham. Elizabeth, it seemed, could not be accused of being excessively maternal, which may merely have reflected the expectations of her upbringing, but hers was an approach that would lead to painful accusations later in life when Charles laid bare his feelings about his upbringing. He, meanwhile, was forming a close bond with his grandmother, which would become one of the most important relationships of his life.

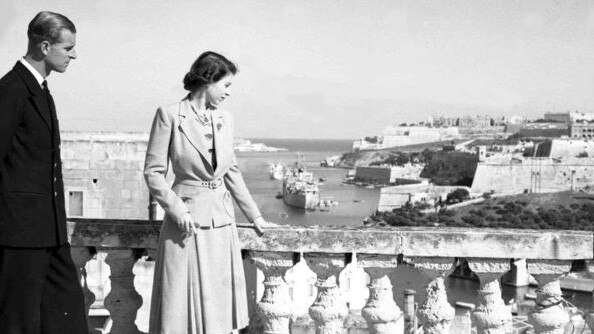

Malta, where Elizabeth stayed for three periods between 1949 and 1951, offered some of the happiest times in her life. For the first time she was able to do all those ordinary things that other people take for granted – to swim in the sea, to go for picnics, to drive a car around the streets, even to do her shopping with her own money. She went to the hairdresser and spent time with the other naval wives – and did not seem to miss Charles at all.

While in Malta she became pregnant again and returned to England to give birth to Princess Anne, later known as the Princess Royal, who was born at Clarence House on August 15, 1950. That Christmas Charles and his sister went to Sandringham while their mother returned to Malta.

While Elizabeth was starting her own family Crawfie, the governess who had devoted 16 years of her life to the two princesses, had married and retired from royal service. Egged on by her acquisitive husband, she signed a lucrative deal to write a book, The Little Princesses, which would be serialised in the US magazine Ladies’ Home Journal. It was harmless, sugary stuff, but the royal family never forgave what they saw as a terrible betrayal. “Doing a Crawfie”, as it became known, was one of the ultimate royal sins and neither of the princesses could even bear to have her name mentioned in their presence. When one visitor forgot, it prompted a sneer of frightening disdain from Princess Margaret: “Crawfie? She snaked.”

Elizabeth and Philip’s final return from Malta was prompted by the declining health of the King. He had cancer diagnosed – not that the word was used in public – and a lung was removed; the operation was successful, but his doctor knew he did not have long. Elizabeth and Philip stepped in to take the place of the King and Queen on a tour of Canada and the US. It was only a moderate success; the Canadian press decided that she often looked distracted or bored. “Why doesn’t she smile more?” they asked.

The following January the couple set off for a tour that was due to take them to Australia and New Zealand, taking in Kenya on the way. The King came to see them off at Heathrow. Margaret MacDonald, by now the princess’s dresser, said he told her, “Look after the princess for me, Bobo,” and that she had never before seen him so upset at parting from her.

George VI died in his sleep at Sandringham on February 6, 1952; Elizabeth became Queen while sitting on the platform of Treetops Hotel in Kenya, watching the animals at a salt-lick from the branches of a giant fig tree. The news took some hours to reach her, by which time she and Philip had returned to Sagana Lodge, their wedding present from the people of Kenya.

Mike Parker, who had been alerted by telephone, broke the news to Philip. “He looked as if you’d dropped half the world on him,” Parker recalled. “I never felt so sorry for anyone in all my life.”

Philip told his wife. “He took her up to the garden,” Parker said, “and they walked slowly up and down the lawn while he talked and talked and talked to her.”

Martin Charteris, who had replaced Colville as her private secretary, found the new Queen sitting at her desk writing letters of apology for the cancellation of the tour. She was “very composed, absolute master of her fate”, he recalled. A slight flush on her face was the only sign of emotion. “What are you going to call yourself?” he asked. “My own name, of course – what else?” she replied.

On the flight home there was little talk, other than Charteris briefing the Queen on what to expect on arrival. One observer recalled that once or twice she left her seat and when she returned looked as if she had been crying. At Heathrow, Churchill was the first to greet her, but was so overcome with emotion that he could not speak. At the meeting of the accession council at St James’s Palace she read the formal declaration of sovereignty to the assembled privy counsellors, and then said: “My heart is too full for me to say more to you today than that I shall always work as my father did …” Outside, in the car with Philip, she broke down and sobbed.

In the period of change that followed politicians seized on the accession of this young woman – she was still only 25 when she became Queen – as the dawning of a new “Elizabethan age”. Churchill hoped for “a golden age of art and letters” and a time of “true and lasting peace”. For others optimism came less easily. Her mother, now styled Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother and widowed earlier than she had expected, not only felt the grief at the loss of her husband, but found it hard to cope with the reversal of status between her and her daughter. Philip saw his naval career come to an abrupt end as he was transformed from being a man with a promising future to someone whose existence consisted of walking forever in the shadow of his wife.

The discomfort he felt in being sentenced to play second fiddle for the rest of his life was painfully highlighted by the business of the family name. Word reached the Palace that Lord Mountbatten – the ever-thrusting Uncle Dickie – had been boasting that “the house of Mountbatten now reigned”. Queen Mary was outraged, the cabinet was furious, and Philip’s tactless if well-argued attempts to put his case infuriated them still further. He told friends: “I am the only man in the country not allowed to give his name to his children.”

After a fierce row the Queen was prevailed upon to issue a declaration saying that the family would continue to be known as the House of Windsor. For Philip it was nothing less than a slap in the face, and he took it hard. “I’m nothing but a bloody amoeba,” he exploded. The episode demonstrated what would become ever more apparent during the many years of her reign, that there was a natural conservatism to the Queen, allied to a tendency to go with the guidance offered by her advisers. During the preparations for her Coronation – which, because of all the work involved in organising such a spectacle, to say nothing of the timetabling of the official guests, would not be held until June 1953 – the suggestion was mooted that the ceremony should be broadcast on the fledgling medium of television. The Queen was firmly against. A fundamentally shy woman, not only was she worried that any mishaps would be transmitted live – and here memories were fresh of the litany of foul-ups that had bedevilled her father’s Coronation – but she also felt that certain elements of the ceremony, such as her anointment and the taking of Holy Communion, were sacred and private. When the decision was made public, the press were up in arms, although wiser newspaper editors took care not to hold the Queen responsible for what they viewed as a reactionary decision, but attributed blame instead to her advisers. After an avalanche of protest the Queen agreed to a compromise: the television cameras would be allowed into the abbey, but there would be no close-ups and no filming of the more sacred moments.

While the Queen remained distrustful of television – her Christmas broadcast would not be televised until 1957 – a precedent had been set: she had shown that, faced with overwhelming public opposition, she was capable of changing direction. Regal concessions would be made again at various flashpoints in her reign – the Windsor fire in 1992, the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1997 – but the pattern was set in 1953.

The week of the Coronation was wet and windy, but that did not stop half a million people turning out by the evening before to secure their place by the side of the road. The sense of celebration was enhanced by the news, published in The Times, that a Commonwealth team of climbers had just conquered the highest mountain in the world. As the Daily Express captured it in a famous front-page headline: “All This – And Everest Too!”

Indeed, it was a day rich with Commonwealth reminders. The Queen wore a dress of white satin, embroidered by Hartnell – at her suggestion – with symbols of the Commonwealth countries: the lotus flower of Ceylon, the wattle of Australia and the wheat and jute of Pakistan, as well as the English rose, the Scottish thistle and the Welsh leek. In the procession down The Mall to the abbey, no one captured the imagination of the crowd quite so successfully as Queen Salote of Tonga, an enormous figure who cheerfully ignored the rain as she rode along in her open carriage.

For the Queen, the solemn ceremony was an affirmation of the vow of service that she had given on her 21st birthday. For those who watched, it was a spectacle, a celebration of national sovereignty, a romantic parade, even a last great imperial display. And for the broadcasters and newsreel companies it was a show whose popularity broke all records. In the US and Canada nearly 100 million people are said to have watched the Coronation on television, making it the top-rated production of the year. The mass media had discovered the unmatched power of royalty, especially young, glamorous royalty, and it was a lesson that they would never forget.

The Coronation also had one other, unforeseen consequence. Princess Margaret was seen to brush – “with a tender hand”, no less – some fluff from the lapel of Group Captain Peter Townsend, George VI’s former equerry who was then employed by the Queen Mother as master of her household. This immediately fired gossip about a romance and the New York press ran the story the next day. It took another 11 days before The Sunday People in Britain reported that the overseas press were saying that Margaret “is in love with a divorced man and that she wishes to marry him”. The bitter saga that ensued, which ended three years later with Margaret deciding to give up Townsend rather than her royal status, can be seen with the benefit of hindsight to show how much attitudes have changed in the past 60 years. It is also revealing about the Queen. Although sympathetic, she was advised by Churchill and Sir Alan Lascelles, her private secretary, that marriage was out of the question. When Margaret turned 25 she could marry without the Queen’s consent, but she would still have to get parliamentary approval, which was unlikely to be forthcoming.

With the Queen Mother typically simply refusing to discuss the matter, the Queen – who believed, probably correctly, that marriage to Townsend would end in disaster – thought Margaret should make up her own mind, but refused to go so far as to tell her so. Instead, she avoided the issue. From the best of motives she was unable to be cruel to be kind and failed to take the tough decisions when they were needed. It would not be the last time the public dimension of her family’s private life would end up causing great personal unhappiness.

Notwithstanding the criticism of the Townsend affair directed at the Palace, the early years of Elizabeth’s reign were characterised by the great sense of optimism that surrounded the young Queen. Churchill, who when she first acceded to the throne feared that he would never be able to relate to her because she was “only a child”, was soon smitten. He would turn up for his weekly audiences in a frock coat and top hat looking positively jaunty, and over time his half-hour meetings would stretch to up to an hour and a half. Asked once what they talked about, he replied: “Oh, mostly racing.”

If Churchill was more than a little bit in love with the Queen, he was not the only one. “The world’s sweetheart,” one American financier called her, and in doing so did no more than give voice to popular sentiment. When she and Philip embarked at the end of 1953 on a six-month, 43,000-mile tour of the Commonwealth, taking in everywhere from Bermuda to the Cocos Islands, and including a three-month sojourn in Australia and New Zealand, she was greeted everywhere with an extraordinary wave of adulation. In Australia it was estimated that three quarters of the population came out to see her; in New Zealand she was welcomed by the Maori as “the rare White Heron of the Single Flight”.

Such a mammoth tour – the like of which had not been seen before, and would not be seen again – was an endless ordeal of speeches and banquets and troop inspections, during which she struggled, unsuccessfully, to keep a smile on her face at all times. “Isn’t she looking cross?” people would say, disappointed that she was not as delighted to see them as they were to see her. That did not mean, however, that she was not capable of seeing the comical side of it all. On one occasion she had the rest of the royal party in stitches when she performed her own interpretation of the haka in evening dress, complete with grunts and exaggerated gestures. Charles and Anne, of course, stayed at home, although they did come out to visit their parents during a stopover at Tobruk, in Libya; a formal handshake from Charles for his mother in public, and no hugs until they were in private.

At home the Queen was already proving herself to be an assiduous constitutional monarch. Like her father – and unlike her uncle, Edward VIII – she made a point of reading thoroughly her government red boxes and would enjoy catching out ministers who might have skimped their official briefs. Churchill, who became somewhat lazy in his later years, fell foul of this; so too did Harold Wilson, who was furious with himself to be caught out on his first audience. After that they got on very well and on at least one occasion he was asked to stay for drinks. “The Queen never reads a book,” said one of her private secretaries, “but when it comes to state papers she is a very quick and absorbent reader – doesn’t miss a thing. She impresses all the prime ministers.”

Despite her hard work and professionalism, Britain was changing, along with its place in the world, and it was the Suez crisis that brought this message home. Britain’s bungled attempt to recapture the Suez Canal in autumn 1956, just over two months after it had been seized by Egypt, dealt the country’s national standing a blow from which it would not quickly recover. However, it was the political ramifications that would lead to questions being asked about the role of the Queen.

When Anthony Eden resigned the following January, the Conservative Party set about replacing its leader by commissioning an elder statesman, the Marquess of Salisbury – “Bobbety”, a man known for his inability to pronounce his Rs – to take soundings. The choice was between RA Butler, known as Rab, and Harold Macmillan, prompting Salisbury’s famous question to members of the cabinet: “Well, which is it? Wab or Hawold?” The Hawolds had it, by an overwhelming majority; but the newspapers, who preferred Wab, were outraged at what they felt was an establishment fix. And the suspicion was that Elizabeth was guilty of naivety in allowing herself to be talked into supporting the chosen candidate of the aristocratic ruling class. This may have been unfair – it is hard to see what she could have done without being accused of meddling in politics – but it reflected a growing feeling in the country that the old school-tie network had had its way for too long.

An incendiary article by a young peer, Lord Altrincham, in the periodical The National and English Review, not only laid into her courtiers – “the ‘tweedy’ sort”, he said, who had failed to move with the times – but also criticised the Queen herself. Her speeches were “prim little sermons” and her style of speaking “a pain in the neck”. Laying the blame on her entourage rather than the Queen herself, he wrote: “The personality conveyed by the utterances which are put into her mouth is that of a priggish schoolgirl, captain of the hockey team, a prefect and a recent candidate for confirmation.” The Queen was furious. She had, according to one source, already been planning to get rid of one outdated palace custom, that of debutantes being presented at court, but kept it going for one more year just to show that she was not going to bow to Altrincham.

For all the uproar, more progressive voices within the Palace realised that there was something in what Altrincham had said. He was invited for a private meeting with Martin Charteris, the Queen’s assistant private secretary, and 30 years later Charteris would tell Altrincham during a political meeting at Eton: “You did a great service to the monarchy and I’m glad to say so publicly.”

Philip was a significant force driving the slow but steady modernisation of the monarchy, such as the lunches that the Queen would hold at Buckingham Palace – initially confined to establishment figures, but later to include actors, writers and sports personalities – but he also became the focus of unwelcome gossip. During 1956 he embarked, accompanied by Mike Parker, on a four-month tour of the outlying territories of the Commonwealth on the Royal Yacht Britannia. An expensive, not to say indulgent, expedition that seems hardly credible now, it was almost at an end when the press got hold of the story that Parker’s wife was suing him for divorce. That, and the fact that Philip was away for so long, gave the US papers the excuse they needed to start digging into the rumours surrounding Philip’s marriage.

It was not the first time that the press had linked Philip with another woman: the gossip columnists had already indulged in speculation about the duke and Pat Kirkwood, the musical star. This time the allegation was that Philip had enjoyed regular assignations with a woman at the Soho flat of his friend Baron, the society photographer who was the linchpin of the mildly louche Thursday Club, whose members would meet for lunch at Wheeler’s in Soho and tell risque stories. Goaded by such headlines as “Report Queen, Duke in rift over Party Girl” the Queen instructed her press secretary to issue a statement denying that there was any such rift, which merely provided the papers with the ammunition for yet more unhelpful headlines.

The fuss soon settled down, but the questions never fully went away. While Philip would defend himself against charges of infidelity by pointing out how he was permanently saddled with his police bodyguards, there was no doubt that he enjoyed the company of close female friends, such as Lady Romsey, who was married to Lord Mountbatten’s grandson and with whom he used to enjoy carriage driving.

Sacha Abercorn, another close friend of Philip, said that theirs was a friendship of ideas. “I did not go to bed with him,” she told Gyles Brandreth, the writer and broadcaster. “I can understand why people might have thought it, but it didn’t happen … he isn’t like that … he needs a playmate and someone to share his intellectual pursuits.” As for the Queen, Abercorn said: “She gives him a lot of leeway. Her father told her, ‘Remember, he’s a sailor. They come in on the tide’. ”

Her reference to Philip’s intellectual pursuits highlighted one of the key differences between him and Elizabeth: that while he had a restless curiosity about the world of ideas, she had little time for intellectuals or writers. Daphne du Maurier, whose husband “Boy” Browning worked for Philip during the early years of the Queen’s reign, found him quick and easy to talk to, but Elizabeth heavy going. She was good on politics and world affairs and lit up whenever the conversation turned to horses, but struggled when it came to literary matters.

As a child, Elizabeth told Horace Smith, her riding master, that when she grew up she would like to be “a lady living in the country, with lots of dogs and horses”, and she always appeared happiest when she was at Balmoral or Sandringham, surrounded by her animals.

That passion for country pursuits came with a deep knowledge too, whether it was for gun dogs or thoroughbreds. Her grandfather, George V, named a bay filly Lilibet after her and her most successful horse was Aureole, who won 11 of his 14 races. The story goes that on the morning of the Coronation, just as she was about to leave the palace for Westminster Abbey, a lady-in-waiting asked her if everything was all right. Oh yes, replied the Queen: she had just heard from Aureole’s trainer, and everything had gone well in his preparation for the Derby (which took place four days later, with Aureole coming second, the Queen’s best result in the one classic that she never won).

For all their differences, the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh enjoyed a relationship in which they gave love and respect, and a measure of freedom, and received in return the support that, for her at least, was the only way she could carry out her role. That was not to say that their marriage was not prey to the tensions that afflict every relationship. In Australia, during their Commonwealth tour of 1953-54, a local camera crew was waiting to shoot some footage of the Queen when Philip ran out of the chalet where the couple were staying, with a pair of tennis shoes and a racket flying after him. The Queen appeared a moment later, shouting at Philip to come back. Eventually, she dragged him into the chalet and the door was slammed. Later, she was charm itself to the camera crew. “I’m sorry for that little interlude but, as you know, it happens in every marriage,” she said. “Now, what would you like me to do?”

Beyond exposing the fact that the Windsors experienced the same marital storms as anyone else, the episode also reflected the changing dynamic of the relationship between the monarchy and the media. The cameraman dutifully handed over his film of the row to the Queen’s press secretary; indeed, on the same tour a government delegation arrived at the Australian Daily Mirror demanding the surrender of a photograph of the Duke of Edinburgh with a drink in his hand. Fifteen years later, in 1969, the royal family would allow the cameras in to film a family barbecue; and in 1994 the Prince of Wales would be on television confessing adultery.

After a decade of marriage the Queen and Prince Philip decided to have more children. It took two or three years of trying, from when Philip returned from his four-month cruise on Britannia, but when she became pregnant the couple were overjoyed. The Queen thought that it was extraordinary, after so long. It did, however, mean cancelling a planned visit to Ghana. Charteris was dispatched to Accra to break the news to Dr Kwame Nkrumah, the country’s leader, who told him: “If you had told me my mother was dead, you couldn’t have given me a greater shock. I have put all my personal happiness in it [the royal tour].” He got over his disappointment, and when the Queen finally visited Ghana, Charteris said, she “twisted him round her little finger”.

Her pregnancy was not the only sign that the marriage was on a sound footing. In February 1960 the Queen announced a compromise on the delicate question of the family name: from now on, she said, while the royal family would continue to be known as the House of Windsor, descendants who were not a prince or princess – in other words, the ones who would actually use a surname – would bear the name Mountbatten-Windsor. The decision was plainly the result of much heart-searching; Harold Macmillan, who talked it through with the Queen at Sandringham, told friends that “it was the first time he had seen the Queen in tears”.

Prince Andrew was born on February 19, 1960; Prince Edward followed four years later, on March 10, 1964. It was while pregnant with Edward that the Queen found herself once more at the centre of a constitutional row over the leadership of the Conservative Party.

As he contemplated his resignation in the aftermath of the Profumo scandal, Macmillan was in hospital, but determined to ensure that his rival, Rab Butler, did not get the job. The Queen was equally determined not to repeat the mistakes of the last time. After she visited Macmillan in hospital, when he gave her the name of Alec Douglas-Home, 14th Earl of Home, she did not give Douglas-Home the job at once, but invited him to see if he could form a government commanding a Commons majority.

This he was able to do, and he was confirmed as prime minister. Yet it did not remove the suspicion that it had been another stitch-up by the grouse-shooting classes: as Tony Benn put it, becoming a Tory prime minister was not so much a question of first past the post, but first past the palace. Once more the Queen had been made to look as if she were capable of siding only with the Tory party’s tweedy tendency.

If her role in Macmillan’s succession is still the subject of debate among constitutional historians, her slow response to the Aberfan disaster was more of a puzzle. In 1966, 144 people were killed, 116 of them children, when a slagheap collapsed on the Welsh village. At a time that called out for a spontaneous gesture, the Queen did not visit the scene for eight days. It was, supposedly, because she did not want to interrupt the rescue and rehabilitation work; it may also have been because she did not like to intrude on private grief or to show raw emotion in public. Charteris would describe her as a woman whose skill was to know when to say no, rather than to come up with ideas. “She’s got superb negative judgment,” he said. “But she’s weak at initiating policy, so others have to plant the ideas in her head.” Later she would admit privately that her delay in visiting Aberfan was a mistake and she wished she had gone earlier.

In other ways, and particularly overseas, she was increasingly confident in her role, and the globetrotting monarch spent the Fifties and Sixties on a series of groundbreaking foreign tours. On her visit to India in 1961, when she was the first British monarch to visit the country since her grandfather, George V, 50 years earlier, more than a million Indians turned out in New Delhi to welcome her. The effect, however, was spoilt somewhat by Philip shooting a tiger on a hunt, which went down badly at home.

The visit later that year to Ghana, postponed from when she was pregnant with Andrew, was overshadowed by Dr Nkrumah’s ever more anti-western stance as well as bomb attacks in Accra. However, the tour was a great success: the country’s neo-Marxist Evening News said that all Ghana had been moved by this “most modest, loveable of Sovereigns” and called her “the world’s greatest Socialist Monarch in history”. A state visit to Germany in 1965, the first by the royal family since before the First World War, caused the Queen much anxiety beforehand but, thanks to the warm reception she received, turned out to be a far more enjoyable experience than she had anticipated.

Others were less enjoyable. A visit to the UK in 1963 by King Paul of Greece and his wife, Queen Frederica, which was controversial because of the Greek government’s civil rights record as well as Frederica’s alleged Nazi sympathies, led to the crowd booing not only the Greek king and queen but also the British royal family. Elizabeth’s tour to Canada the following year, which drew protests in Quebec, was one of the most difficult that she had undertaken. In a conciliatory speech she stated that a “dynamic state should not fear to reassess its political philosophy” and remarked that it was not surprising that “an agreement worked out 100 years ago does not necessarily meet all the needs of the present”. She received a better welcome in Ottawa, but it was admitted that the tour had “undoubtedly given rise to more controversy and anxiety, in Canada and Britain, than any before it”.

On the domestic front they were now a family of six. While Elizabeth was accused of lacking maternal feeling – a criticism highlighted by Charles’s complaints about his upbringing, which would surface in Jonathan Dimbleby’s biography in 1994 – she was overjoyed to have Andrew and Edward, and was more relaxed with them than she ever was with Charles and Anne. “Goodness what fun it is to have a baby in the house again!” she told a friend after Edward was born. Her favourite night of the week was “Mabel’s night off”, when the nanny was out and she could put the boys to bed herself.

Her instinct was to protect her family’s privacy, but as the decade progressed it became apparent that something needed to be done about the royal family’s public image, which was seen as fusty and out of date. Persuaded by the Mountbattens and William Heseltine, her bright new Australian press secretary, the Queen agreed to let the cameras in. Royal Family, which was first shown in July 1969, was a revolution in the way that the royals were depicted on screen. Until then it was unheard of to see the Queen working on a speech with her private secretary, let alone relaxing with her family on a picnic beside Loch Muick at Balmoral.

The results revealed the naturalness and spontaneity of a woman who, in formal contexts, came across as stiff and remote. Among the footage of state visits and private audiences there were shots of Charles bicycling in a London street, Philip grilling steaks on the barbecue, the family sitting around the lunch table telling not particularly funny stories. They were, in other words, just another family. Since then commentators have argued about whether it was wise, to borrow Bagehot’s phrase, to let daylight in upon magic, and whether the film created the public appetite for insight into the personal lives of the royal family, thus leading to the flood of prurient and intrusive media coverage that would be unleashed little more than a decade later with the arrival on the scene of Lady Diana Spencer. Most likely it would have happened anyway.

There were other changes afoot in the way that the royal family revealed themselves to the public. Charles’s investiture as Prince of Wales at Caernarfon Castle on July 1, 1969, a colourful, television-friendly pageant that commanded enormous viewer ratings, demonstrated new ways of presenting the royal family in a media age, which emboldened them to more colourful showmanship in later parades and jubilees. The following year in New Zealand, with crowds larger than expected, the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh took an apparently unscheduled and casual walk along the street, shaking hands and chatting with the public. Such performances are commonplace now, but then they were a radical departure from accepted practice. A reporter borrowed a word previously used to describe the wanderings of Australian Aborigines in the bush: the walkabout was born.

In 1972 the Duke of Windsor died. The lasting rift between the abdicated king and the royal family had been an issue throughout the Queen’s reign. He had not been invited to the Coronation, because it was felt constitutionally inappropriate, although there was a reconciliation in 1965 when the Queen visited her uncle while he was in London for an eye operation. Ten days before he died she visited him at his home in the Bois de Boulogne, in Paris. According to his doctor there were tears in her eyes as she left; she had been moved by the meeting, which brought back memories of her own father. After a funeral at St George’s Chapel, Windsor, the duke was buried at Frogmore, where he would be joined by the duchess 14 years later.

The Silver Jubilee in 1977 was a surprising success, as indeed was every jubilee that followed, suggesting that, whatever the media might say, and whatever day-to-day grumbles people might have had about the royals, there was an underlying respect and affection for the Queen that was remarkably resilient. With the economy in the doldrums, the government did not want to spend any money and the Queen – modest as ever – did not want any overblown celebrations, but in the event the commemorations in June led to a spontaneous outpouring of popular feeling. There were flags, bonfires and street parties. The Queen was quite taken aback at it all. “She could not believe that people had that much affection for her as a person, and she was embarrassed and at the same time terribly touched by it all,” said her domestic chaplain.

After Edward Heath, who the Queen found hard work, and James Callaghan (who astutely observed that what the Queen offered her prime ministers was “friendliness but not friendship"), the election of Margaret Thatcher as prime minister in 1979 brought fresh challenges. In many ways the two women could not have been more different. The Queen was naturally conservative and a countrywoman at heart, while Thatcher was a radical and did not have a country bone in her body; bracing walks at Balmoral were something she endured rather than enjoyed. Their greatest divergence of opinion was over the Commonwealth, an institution whose leadership the Queen had inherited from her father and to which she gave her utmost dedication. Thatcher was far from keen.

While the Queen never took sides publicly, according to Sir Sonny Ramphal, the secretary-general of the Commonwealth, there was no doubt where she stood on the divisive issues of the time: Rhodesia and apartheid. In 1979, when Britain was unpopular with black African leaders because of its failure to help to bring about a solution to the fighting in Rhodesia, the Commonwealth summit in Lusaka, in Zambia, looked set to be a disaster; yet somehow it was a success, with an accord that would lead to the foundation of Zimbabwe.

Behind the scenes the Queen, who knew many of the African leaders of old, is considered by many to have played a part. In Ben Pimlott’s analysis she was an emollient, a figure outside politics who had an understanding of both sides of the argument. “She talked to Mrs Thatcher and to [Kenneth] Kaunda [the Zambian president],” said Ramphal. “The fact that she was there made it happen. Kaunda felt that he’d have let her down a little if he hadn’t pulled it off.” Her differences with Thatcher emerged in spectacular fashion with a Sunday Times story that said the Queen was dismayed by Thatcher’s policies over a wide range of issues, including the crisis in the Commonwealth over South Africa. She found the prime minister’s approach to be “uncaring, confrontational and divisive”, the paper said.

The source for the story was Michael Shea, the palace press secretary, but whether he went too far in representing an anti-Thatcher view, or whether The Sunday Times exaggerated his remarks, will remain a subject for conjecture. Either way, the Queen stood by him. The evidence, however – the Order of Merit that the Queen conferred on Thatcher after her resignation, and the fact that she attended her funeral – implies that the Queen had more time for the first of her three female prime ministers than a casual reading of events would suggest.

One embarrassment that Thatcher could have lived without was Michael Fagan’s break-in at Buckingham Palace. Fagan, a 33-year-old man with schizophrenia, had managed to bypass security and get into the Queen’s bedroom on the morning of July 9, 1982. Unable to raise help, the Queen talked to him sympathetically for ten minutes until he asked for a cigarette, which she used as an excuse to get him out into the corridor. The maid, who had been vacuuming in the next room, exclaimed: “Bloody ‘ell, Ma’am, what’s ‘e doing ‘ere?” Moments later the police arrived. “Oh come on, get a bloody move on,” said the Queen, as one officer paused to straighten his tie.

The previous year there had been another security scare when a youth in the crowd at Trooping the Colour fired six shots, which turned out to be blanks, at the Queen as she rode by. Showing remarkable coolness under fire, she ducked, patted her horse Burmese, and rode on.

The Queen had already been on the throne for nine years when the woman who would have a greater impact on the monarchy than anyone since Wallis Simpson was born. When, in the second half of 1980, Charles began to take Lady Diana Spencer seriously as a possible bride, his parents were concerned that he was in danger of dithering for too long. The Queen voiced her feelings to a friend, but said nothing to Charles; Philip had to tell his son that he had to propose or end the relationship.

Diana’s sense of alienation began when she moved into Buckingham Palace before the wedding. She felt lost, overawed and ignored. However much truth there was in that – palace insiders said they went out of their way to help her – she and the Queen had little in common. As the marriage deteriorated and a partisan war developed between Charles and Diana’s camps, the Queen and her advisers stood accused of failing to understand the glamorous and widely adored princess, of cold-shouldering her and squandering an asset that had given the royal family its first international superstar.

At pains not to take sides, the Queen felt that she could not interfere to help to save her son’s marriage; later, when the couple’s relationship neared the point of no return, it was the Duke of Edinburgh who took the initiative. After a meeting between Elizabeth and Philip and Charles and Diana at Windsor, which went some way towards clearing the air but failed to achieve anything substantial, Philip began in 1992 writing a series of letters to Diana that were frank, direct, but sympathetic and more than aware of Charles’s faults. They achieved little, other perhaps than to upset the eternally fragile Diana. Eventually there was nothing more that Elizabeth and Philip could do, although the Queen made one last attempt to hold things together by persuading Diana and Charles to go ahead with a joint visit to South Korea. It was not a good idea. The tour was a disaster, with the couple clearly unable to bear the sight of each other, which merely provided the press with more ways to write about the collapsing marriage. Shortly after their return Charles decided there was no future in their marriage and asked his wife for a legal separation. It was announced on December 9.

Before that, there was worse to come. On November 20, Philip and Elizabeth’s 45th wedding anniversary, a fire broke out at Windsor Castle when a restorer’s lamp set a curtain alight. Within hours the fire was out of control, badly damaging St George’s Hall, the state dining room and three drawing rooms, and destroying several roofs. The Queen was devastated; not only was Windsor the symbol of the monarchy, it was her childhood home and the place she loved more than anywhere else.

Four days later she gave a speech at Guildhall, London. The lunch was to celebrate her 40th year on the throne but instead came to mark everything that had gone wrong in that most disastrous of years for the royal family. As well as the Windsor fire and the breakdown of Charles and Diana’s marriage, there had been the divorce of Princess Anne and Captain Mark Phillips, the separation of the Duke and Duchess of York (whose marriage had collapsed amid a series of lurid exposes in the press, including photographs of the duchess having her toes sucked by John Bryan, her “financial adviser"), and the publication of a recorded phone call between Diana and her lover James Gilbey (the “Squidgy” tape). “1992 is not a year on which I shall look back with undiluted pleasure,” the Queen said. “In the words of one of my more sympathetic correspondents, it has turned out to be an annus horribilis.” The Sun translated it as “One’s Bum Year”.

Two days after that John Major, the prime minister, announced that the Queen and the Prince of Wales would pay income tax and that the Queen would – out of her income from the Duchy of Lancaster – reimburse the civil list annuities received by the Princess Royal, Prince Andrew, Prince Edward, Princess Margaret and Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester.

Controversy over the money allotted for the royal family had been a running sore for decades. When she was still Princess Elizabeth there was resentment about how much she would get from the government on her marriage to Philip. In 1969 he had blundered on US television when he announced – during negotiations between the Palace and the government that until then had been conducted in secret – that the royal finances were so tight that he might have to give up polo.

Major’s statement was a woeful public relations own goal. It gave the impression that the Queen had been panicked into paying income tax by the furious public reaction to the announcement by Peter Brooke, the heritage secretary, that public money would be used for the repair of Windsor Castle, estimated at pounds 60 million. In fact, negotiations about tax had been going on behind the scenes for many months, but it suggested that she had caved in to a tabloid campaign.

The broader point was still true, however; her decision to agree to remove the anomaly over income tax was indeed a response to public criticism of the monarchy and the way it was financed. It was just a question of timing. The following spring Major announced that the restoration of Windsor Castle would not be funded by public money, but mainly by opening parts of Buckingham Palace to the public.

The question of money would continue to bedevil her reign. In the 1980s under Lord Airlie, the Lord Chamberlain, the Queen instigated an overhaul of the way that the Palace and its finances were run, which saved millions of pounds. Gratitude, however, was in short supply. Most of the money-saving measures met with the approval of the Queen, a naturally thrifty person. However, the axing of Britannia in 1997 was a decision motivated by politics as much as money and the Queen was seen to dab a tear from her eye as it was decommissioned. In 2012 George Osborne, as chancellor, in an attempt to stave off the political rows that invariably surrounded the civil list, introduced the sovereign grant. The rows, of course, continued.

The aftermath of Charles and Diana’s separation left Elizabeth depressed by the family situation and its repercussions. She and Philip would wonder – as indeed would many others – to what extent they were to blame for the failure of not only one but three of their children’s marriages. “What did we do wrong?” they would ask friends. There were more unpleasant surprises in store. From the Queen’s point of view the 1994 television film that Charles made with Jonathan Dimbleby, in which he confessed to adultery with Camilla Parker Bowles (but not “until the marriage had irretrievably broken down"), was bad enough; Dimbleby’s biography was worse. Charles, through Dimbleby, laid much of the blame on the way his parents had brought him up. His mother had been remote, and his father a bully. Both had been “unable or unwilling to proffer … the affection and appreciation” that he craved. Relations between Charles and his mother had not been easy for a long time. Over the years their relationship became ever more distant, partly because they were not living under the same roof, and partly because of a failure to communicate on any deep, personal level. They exchanged social pleasantries and dealt with family business, but little more than that. As Charles gained confidence, the rift between his household and the Queen’s grew wider. “Though the prince disguised his growing resentment – except from his intimates,” Dimbleby wrote, “he was quick to detect any apparent slight from the Queen’s officials and began resolutely to distance himself from them.”

However cool things were between Elizabeth and her eldest son, the accusations about his upbringing still came as a bitter blow. She put a brave face on it. Her other children were outraged by what Charles had said about their parents and told him so.

Diana’s interview on Panorama, in which among other things she cast doubt on whether Charles was fit to be king, was the spur that finally persuaded the Queen that the situation had become so intolerable she had to take the initiative. Just before Christmas 1995 she wrote to Diana and Charles advising them that they should begin divorce proceedings. The marriage formally came to an end on August 28, 1996.

Almost exactly a year later Diana was killed in a car crash in Paris. In the week that followed, a spontaneous public outpouring of grief for Diana was accompanied by a groundswell of opinion that the Queen, who was at Balmoral with Charles, William and Harry when the news broke, had somehow failed to respond in a way that the press and public deemed appropriate.

Far removed from the emotional turmoil in London, the Queen, who had no precedent to fall back on, was at first unsure how to react. Her natural desire was to protect her grandsons, which meant keeping them at Balmoral, away from the limelight. Her default position was to do what she always did at times of stress – to rely on tradition and routine to see her through.

On the morning of Diana’s death, therefore, the family went to morning service at Crathie Kirk as normal. The boys were told that they did not have to attend, but decided they would because it was preferable to being left behind. A perfectly sensible decision, from the Balmoral perspective; to the outside world it came across as the Windsors in typically cold-hearted fashion forcing the boys out in public. There was more outrage over the flag: why was the Union Jack not flying at half-mast over Buckingham Palace? The answer, that the Royal Standard is the only flag that flies over the palace, and then only when the sovereign is present – and never at half-mast – did not satisfy anyone. A compromise was reached: the Union Jack would fly over the palace at half-mast.

It was the Queen herself who became the focus of criticism. Why was she hiding away at Balmoral? Why had she not spoken in public about Diana’s death? As the week wore on, she realised that she had to change tack.

On Friday, the day before Diana’s funeral, she flew to London where, highly nervous about the reception she would get from the crowd, she left her car with Philip to look at the sea of flowers outside the palace. But it was all right: the crowd broke into applause and a young girl handed her some flowers. “Would you like me to place them for you?” the Queen asked. “No, your majesty. These are for you,” came the reply.

That evening she spoke live on television of Diana as “an exceptional and gifted human being” who she “admired and respected”. In a conclusion that carried a surprising note of humility the Queen added: “I, for one, believe that there are lessons to be drawn from her life and from the extraordinary and moving reaction to her death.” It was a touching and sincere broadcast that struck the right note and won over most of her critics, but – as the reaction to Earl Spencer’s barbed words about the royal family at the funeral made clear – the Queen knew that the royal family would once more have to change.

Slowly, the family’s stock began to rise. The Queen continued with her daily duties. Contrary to the impression that Diana might have given, Charles proved himself publicly what he had always been privately: a good father to William and Harry.

The death of Princess Margaret in February 2002 and the Queen Mother the next month evoked great sympathy for the Queen. The celebrations for the Golden Jubilee that year showed that the royal ship was back on course and in 2005, after years when it seemed uncertain that Camilla Parker Bowles would ever be welcomed into the royal family, she and Charles married at Windsor. The Queen did not attend the ceremony at Guildhall, but afterwards spoke warmly at the reception at Windsor Castle. In a wry reference to the day’s other big event, the Grand National, she said: “Having cleared Becher’s Brook and the Chair, the happy couple are now in the winner’s enclosure.”

One of the most significant factors in the revival of the family’s popularity was the arrival of Kate Middleton. William and Harry had already shown a new informality in their way of approaching their royal responsibilities, but it was William’s marriage to the daughter of a middle-class couple from Berkshire that showed how the royal family was moving away from its traditional, hidebound assumptions – not least about breeding, in every sense of the word – and adapting to the 21st century. Kate was welcomed into – and protected by – the royal family in a way that Diana never was. So were her parents: while the Spencers had long moved in royal circles, the Middletons were not the sort of people who would have received a social invitation from the royals. Now they were invited to Balmoral, where they were seen flat on their stomachs in the heather being coached in the art of stalking by a ghillie, and Sandringham. The Queen is said to have liked the cosy atmosphere at the Cambridges’ family home, where the duchess’s mother, Carole, has been a regular fixture.

The marriage of Prince Harry to Meghan Markle in May 2018 marked another shift in the royal family’s attitude and relationship to the outside world. A couple of generations earlier the monarchy had an existential crisis over a proposed marriage to an American divorcee: some 80 years later, when Harry’s American divorcee was also an actress of mixed race, the royal family – and the nation – took it all in their stride. The day before the wedding the Queen was spotted being driven through Windsor with Meghan’s beagle, Guy, sitting next to her in the back of the car. Ms Markle, now the Duchess of Sussex, was part of the family, and so was her dog.

When Elizabeth acceded to the throne she was Queen of 32 nations. By the end of the 20th century that number had been whittled down to 16. In 1999 Australia – where memories still rankled over how Sir John Kerr, the governor-general and the Queen’s representative, had sacked Gough Whitlam as prime minister in 1975 – held a referendum on whether the country should become a republic. The voters, unimpressed with the alternatives on offer, voted to keep the monarchy. By the time the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh paid their last, triumphant visit there in 2011, republicanism was well off the political agenda.