A life devoted to service: Queen Elizabeth II, 1926 - 2022

She was only 21 when then Princess Elizabeth pledged herself to her nation, laying down the guiding principle for how she would live and reign.

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, born April 21, 1926. Died September 8, 2022 aged 96

She was just 21 when she said it, on her first trip overseas and still years away from fulfilling her destiny to be Queen. But in that one resonant passage, Elizabeth laid down the guiding principle for how she would live and reign into a future that could barely be glimpsed through the sepia lens of fading imperial glory. “My whole life,” she pledged, “whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service.”

The young princess would marry her sweetheart, become a mother, monarch, matriarch of nations and symbol of stability in a world that moved at a dizzying pace from the crackling radio broadcast that carried her prescient words from Cape Town in 1947 to jet travel, the television age, gender equality, identity politics and the rise and rise of the internet in an era of unparalleled social and technological disruption.

She changed as the times changed, if reluctantly on occasion. When the burden of the crown was thrust upon her with the death of her father, George VI, in February 1952 her beauty and youth became a beacon of hope for a rebadged Commonwealth emerging from the long shadow of world war. The ascension of Queen Elizabeth II was a sunny juxtaposition to the austerity and uncertainty of the postwar years in both the UK and here. She aged in tandem with Australians’ maturing view of the nation’s place in the world and altered relationship with institutions such as the monarchy.

If along the way a head of state ensconced in a palace in far-off London was seen to be increasingly irrelevant, she also came to represent timeless personal virtues: service, sacrifice, duty, modesty and hard work. The Queen was as good as her word in living by the loftiest of standards.

There was a reason that republicans such as Australia’s 29th prime minister, Malcolm Turnbull, accepted constitutional reform would have to wait until she bowed out, one way or another. The affection and respect in which she was held not only endured but deepened. In 2011 Australians flocked in their tens of thousands to what turned out to be a sentimental farewell visit with Prince Philip, whose death in April 2021 affected her profoundly.

When she became Britain’s longest-serving monarch, surpassing the 63-year reign of her great-great-grandmother Victoria in 2015, the Queen characteristically played down the occasion. “Inevitably a long life can pass by many milestones,” she said. “My own is no exception.”

The crown now passes to the Prince of Wales, who at 73 is 48 years older than his mother was when she took the throne. It’s reasonable to expect we will not see her like again. In the foreseeable future, no monarch will come of age so young or with so little life experience and yet face such acute challenges. William, next in the line of succession, is a middle-aged man of 39, and his heir, George, already nine, may have to wait the longest of all the Windsors for his turn to reign.

Arguably, the last vestige of the monarchy’s mystique died with the Queen. The human side of her character – her talent for mimicry, her sense of fun, the way she came to life when she was watching her racehorses run – was subsumed by the strictures she imposed on herself. If she cut a remote figure, it was surely to protect what she saw as the currency of royalty, the magic, if you like, that allowed ordinary people to buy into the fairytale without resenting the Queen’s wealth and life of ostentatious privilege.

But the mask sometimes slipped, as in her “annus horribilis” speech after fire gutted her childhood home of Windsor Castle, capping a disastrous year of 1992 in which the breakdown of the marriage of Charles and Diana and Princess Anne’s divorce from Captain Mark Phillips attracted unsparing media attention, along with the “toe sucking” exploits of Fergie, the then Duchess of York, newly-separated from Prince Andrew, and the leaked “Squidgy tape” conversation between Diana and her lover, James Gilbey. “1992 is not a year I shall look back on with undiluted pleasure,” the Queen said drily.

Still, unlike many people her age, she became more relaxed and open to new suggestions as she grew older. Witness that jaw-dropping stunt with James Bond actor Daniel Craig for the opening of the 2012 Olympics in London.

Diana’s death 15 years earlier had been a turning point in this respect. Initially, the Queen kept her distance from the fervid scenes in London, staying put in distant Balmoral to shield her grandsons, William and Harry. The outcry caused her to reconsider: not only did she jettison protocol to allow the Union Jack to fly at half-mast over Buckingham Palace, she made public appearances and a touching televised address that gentled the ill-feeling. If the Queen presented as being aloof through her long life, she was never entirely out of touch, another secret of her success as monarch.

Of course, she had not been born to rule in the accepted sense. Baby Elizabeth arrived in the early hours of April 21, 1926, the first child of the Duchess of York, the 25-year-old wife of King George V’s second son, Albert, making her third in line behind her father. Enchanted, the gruff, bearded King called her Lilibet, in imitation of her attempts to say her name. At the time, long before anyone had heard of Wallis Simpson, Bertie’s elder brother, David, was the heir to the throne and the reasonable expectation was that the dashing royal bachelor would settle down in due course, marry and raise a family.

The rest is history: as King Edward VIII, David chose the love of the American divorcee over the crown and abdicated in 1936 at the height of a constitutional crisis in the UK. When her father became king, Elizabeth went to next in line, propelling her into the spotlight with her younger sister, Margaret. They were the last generation of British royals to be educated at home.

She was 13 when she encountered a handsome young cadet who spent the afternoon with the princesses during their visit to the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, in July 1939. The 18-year-old Cadet Captain Prince Philip of Greece was tall and charming, another great-great-grandchild of Queen of Victoria. By one account, he was too intent on teasing Margaret to pay much attention to her quiet sister.

Philip had a good war, serving with distinction in action in the Mediterranean. He also wrote regularly to Elizabeth, who kept his photo on the mantelpiece. The princess was largely sequestered at Windsor, frustrated that she wasn’t permitted to do “her bit” for the war effort. Finally, in the northern spring of 1945, not long before the fighting in Europe ended, her father allowed her to join the Auxiliary Territorial Service and take a three-week vehicle maintenance course. She learned how to service an army truck.

By the time she undertook her first overseas trip — the visit to South Africa marked by her famous 21st birthday broadcast – Elizabeth and Philip had become engaged. At the wedding festivities in Buckingham Palace, the King led a noisy conga through the corridors. Philip had been granted the title of Duke of Edinburgh and the style of His Royal Highness; the newlyweds made a fashionable and overtly happy couple. “Elizabeth was physically passionate and very much in love with her husband,” biographer Sarah Bradford would write.

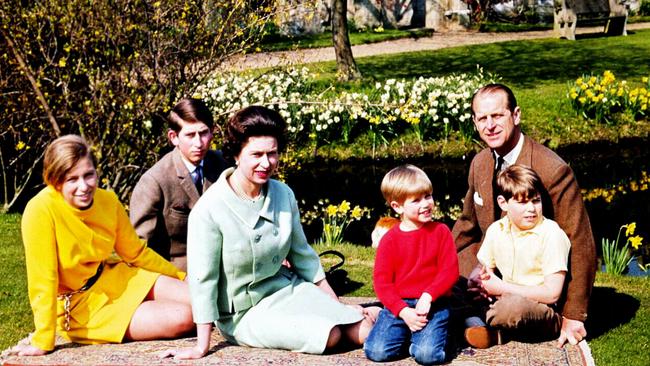

Charles was born in the evening of November 14, 1948, while his father was playing squash with his confidant and private secretary Mike Parker, an Australian shipmate from the war. Philip, still in the navy, was posted to Malta, and she opted to join him at the expense of being separated from their baby son, who stayed with his grandparents at Sandringham. She returned home to give birth to Anne in August 1950.

The chain-smoking king, meanwhile, had been diagnosed with lung cancer – not that the term was used in public. The last time he would see his daughter was to see her off with Philip for a visit to Australia and New Zealand, taking in east Africa. Aged only 56, George VI died in his sleep on February 6, 1952; Elizabeth became Queen while sitting on the platform of Treetops Hotel in Kenya with her husband watching the wildlife congregate at a salt lick. Australia had to wait.

Philip was determined that the children should have his family name, Mountbatten, instigating a test of wills that he lost, to his fury. Tellingly, the Queen was guided by her abundant natural caution, overlaid by the advice of conservative aides. The pattern would take hold during her long reign, as was the case in those fraught days following Diana’s death.

She remained distrustful of TV – her Christmas broadcast would not be televised until 1957 – and at first refused to allow the cameras inside Westminster Abbey for her Coronation in 1953. When the press pushed back against this decision, which was blamed conveniently on palace advisers, not the new Queen, she compromised. The broadcast went ahead absent of close-ups and footage of the more “sacred” moments such as her anointing. Faced with trenchant public opposition, she had shown what would become increasingly apparent as the years went by: if need be, the Queen was for turning.

The viewing records shattered by the Coronation, watched by an estimated 100 million people in the US and Canada alone, delivered another lesson that would be dutifully absorbed. The media made the British monarchy matter when its true relevance in terms of national leadership and political influence was in eclipse. This proved to be something of a double-edged sword, however. In throwing open the doors to wider coverage, the palace was also relinquishing its formerly iron control over what could be reported, the Queen ruefully discovered. The “tender hand” with which Margaret was seen at the Coronation to brush lint from the lapel of her divorced lover, Group Captain Peter Townsend, led to a firestorm over the relationship and an anguished decision for the Queen on whether the couple would be permitted to marry.

The answer was yes, then no, in a saga that dragged out over three years, ending only when Margaret chose to give up Townsend rather than her royal status. The soap opera would continue as the hapless princess bounced into a stormy marriage with the society photographer Antony Armstrong-Jones in 1960, who was created Earl of Snowdon by the Queen. They divorced 18 years later, having raised two children.

After a decade of marriage, the Queen and Prince Philip decided to have more children: Andrew, born in February 1960, with Edward following four years later. She had relented on the family name by then. While the royal family would continue to be known as the House of Windsor, descendants who were not a prince or princess – in other words, those who would actually use a surname – would bear the name Mountbatten-Windsor. The accommodation was driven by her desire to keep the peace with her restless husband. Rumours that Philip enjoyed more than the company of close female friends, which had been swirling in the press as early as 1948, intensified after the wife of his boon companion, Parker, filed for divorce while he was away with the Duke of Edinburgh on a four-month sojourn on the royal yacht Britannia, taking in the opening the 1956 Melbourne Olympics by Philip.

The Queen’s mettle as a constitutional monarch was tested by the Suez crisis, also in 1956, caused by Britain’s bungled effort in cahoots with the French and Israelis to recapture the canal after it had been seized by Egypt, a humiliation that ended any British pretence to be a top-tier power. Prime Minister Anthony Eden resigned, but the Queen was drawn into the row over the Conservative Party’s nomination of Harold Macmillan as his successor; the papers screamed it was an establishment fix, with the implication that she had supported a stitch-up by the manored class. Whatever her view might have been, she could not have intervened without jeopardising her apolitical position; but the broader takeout was that the old school tie still held sway as one Old Etonian was traded for another.

When Macmillan tapped the mat in 1963 in the aftermath of the Profumo scandal over his war minister’s ill-advised dalliance with exotic dancer Christine Keeler, while she had a love triangle going with a Soviet spy, the Queen, anxious to avoid the mistakes of last time, invited his successor, the aristocratic Alec Douglas-Home, 14th Earl of Home, to test the new government’s support in parliament before she confirmed him as prime minister. This he was able to do. But Labour’s Tony Benn tapped the mood with the quip that becoming a Tory PM was not so much question of first past the post, as first past the palace.

Much has been made of her relationship with her other prime ministers, some of whom she did not warm to. Like her father, the Queen never skipped on reading the government “red boxes” filled with voluminous briefing papers and legislation for assent. Harold Wilson was caught out at his first audience; furious with himself, the three-term Labour PM vowed to never again see her unprepared again.

Margaret Thatcher was said to grate on the Queen, who was reported in a bombshell 1986 Sunday Times story, sourced to then palace press secretary Michael Shea, to regard the Iron Lady’s approach as “uncaring, confrontational and divisive”. If so, she had the grace to confer the Order of Merit on Thatcher after her resignation as prime minister and to attend her funeral in 2013.

The Queen had been on the throne nine years when the woman who caused her more grief than any other, Diana Spencer, was born. After marrying Charles in July 1981, the newly-minted princess soon felt lost, overawed and alienated by palace life; as the marriage deteriorated the bitterly partisan war between Charles’s and Diana’s camps played out in the media, polarising public opinion.

The Queen and her advisers stood accused of failing to understand the glamorous and adored Diana, of cold-shouldering her and squandering an asset that had given the royal family its first international superstar. True, the Queen would have had little in common with her flighty daughter-in-law. And in the soul-searching that followed Diana’s death in a senseless Paris car smash in 1997, both she and Philip would wonder to what extent they were to blame for the failure of three of their four children’s marriages.

Compounding this, Charles had revealed to his biographer, Jonathan Dimbleby, the childhood baggage he carried from a remote mother and the father who bullied him. The accusations were said to be a bitter blow to the Queen and, coming after Charles confessed his adultery with Parker Bowles, also to Dimbleby, played into the turmoil that would plumb its nadir as the world mourned Diana.

Yet again the Queen showed her ability to respond to public opinion, albeit with prodding from Tony Blair and the spinners at No. 10. The day before the funeral, after she returned to London, she inspected the sea of flowers that had been laid outside Buckingham Palace, nervous of how the big crowd would respond. The tense mood was broken when a little girl handed the Queen a bunch of flowers. “Would you like me to place them for you?” she asked. “No, your majesty. These are for you,” the child replied.

In a moving televised address, the Queen went on to praise Diana as an “exceptional and gifted human being,” whom she had admired and respected. “What I say to you now as your queen and as a grandmother, I say from my heart,” she said. It was the start of the long and patient effort to rebuild the stocks of the House of Windsor post-Diana and grow support for Charles’s succession, a process that would preoccupy the Queen as her long reign tipped into its twilight phase. Those milestones flew by, thick and fast. The golden jubilee in 2002 was celebrated on the back of an outpouring of sympathy for the Queen following the deaths of Margaret, 71, and the Queen Mother barely a month later aged 101. When Charles married his long-time mistress in April 2005, the public’s acceptance of the relationship was mirrored by Camilla Parker-Bowles’ integration into the royal firm as the Duchess of Cornwall. Her relaxed warmth seemed to bring out the best in the fussy Prince of Wales.

The Queen continued to travel, of course, more than any other monarch in history, visiting every corner of a Commonwealth that had been pared down from 32 countries at the time of her coronation to barely 16. Her first visit to Australia, in 1954, was an epic eight-week undertaking with Philip. In the heat of February and March they visited every state capital and towns by the score, cheered by huge crowds. Three quarters of the nation’s population is thought to have lined one street or another to catch a glimpse of the couple.

What her 16th and final tour here in October 2011 lacked in scale – a relatively modest 10 days, it took in Canberra, Melbourne and Brisbane before she opened a Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in Perth on the way home – the affection for the Queen and Prince Philip was palpable as they undertook the traditional walkabouts among the crowds. The term was actually coined in New Zealand but never mind: Australians aren’t shy of appropriating from their Tasman neighbour. The Queen was the first monarch to embrace this level of interaction with the public; the first to throw open the guest list at Buckingham Palace; the first to let loose the TV cameras on her family life, despite her initial aversion to the medium. How ironic that the reformist ideas of Lord Altrincham, the minor peer who caused such a fuss in 1957 when he urged her to move with the times and stop making “prim little sermons”, would so quickly go from being subversive to core business for the royal firm.

The Queen’s slowdown was gradual. In 2013, palace aides let it be known that she would undertake no further long-haul travel and the following year Charles stood in for her to open the Commonwealth Games in Delhi, backing up to do the honours at the Gold Coast in 2018. The Prince of Wales was subsequently endorsed to succeed his mother as head of the Commonwealth, a position that did not fall to him by hereditary right. Behind the scenes, the Queen had pushed hard for him. In 2013, she secretly sent to Australia her most senior and trusted adviser, Sir Christopher Geidt, to lobby then prime minister Julia Gillard, who was also chair of the Commonwealth. The avowed republican would later say: “I would not want you to think this was some simple act of colonial subservience. I did see wisdom in it.”

Elizabeth’s legacy, perhaps her crowning glory, is personified by her grandsons, William and Harry. Each helped their father shoulder more of her responsibilities in her sunset years. Their glamorous wives, Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, and Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, respectively, enjoyed very different relationships with their grandmother-in-law to the disconnect Diana complained of. The Queen went out of her way to make the young women feel welcome.

What a shame that Harry would leave the royal firm, decamping to Los Angeles with his wife and the children they are bringing up there in lucrative isolation, butresssed by mega-dollar deals with Netflix and other media concerns. Philip’s 2021 death, at age 99, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, was a window into her increasingly lonely world. Images of her mourning her husband of 73 years in a near-empty St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle, face-masked and socially distant from the family, tugged at heartstrings globally. “He has, quite simply, been my strength and stay all these years,” she said, referencing her toast to Philip at their 50th wedding anniversary. “And I, and his whole family, and this and many other countries, owe him a debt greater than he would ever claim, or we shall ever know.”

The antics of Meghan and her ginger-haired grandson would have added to the burden she carried so graciously to her death. Andrew, said to be her favourite child, was forced to withdraw from royal duties over his entanglement with the American paedophile Jeffrey Epstein and claims by a woman, Virginia Roberts Giuffre, that the middleaged prince had sex with her knowing she was being trafficked by the disgraced US businessman.

The early 2020s were among the most confronting years the Queen faced. Yet she never seemed to weary, never complained about the inevitable toll they must have exacted. A rare concession was to use a walking stick. As ever, she was the grand lady of public life in Britain and the Commonwealth, something the advancing years could not gainsay.

Her implacable, indomitable devotion to duty will been carried on by the new King, Charles, and his heir, William, who on precedent will succeed to the title of Prince of Wales. To her immense credit, she bequeaths a crown that is in far better shape than the one she assumed all those years ago. The second Elizabethan age will be remembered as a time of tumult and change, when the social fabric was strained and institutions questioned like never before. Yet thanks to the Queen, the monarchy can look to the future with confidence. She takes her place in history among the most able and revered of British monarchs, her eternal rest richly earned.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout