Putin’s empire is crumbling — will 2025 prove to be his 1989?

Failure in Syria and the fall of Assad, endless war in Ukraine, rejection by eastern states, a loss of influence in the global south: this is not how it was meant to be for the Russian leader. And this year it could get worse.

Last year we were so desperate for things to turn out for the best that we couldn’t stop worrying about the worst. Elections gave populists everywhere some prospect of power but 2024 still didn’t seem like the 1930s. The world’s wars started to thread together but not in a way that suggested an imminent world war. We look for hope in 2025 but have already concluded that hope is irrational.

There is one slim consolation though and it’s this: Vladimir Putin’s ramshackle empire is falling apart. His strongman credentials were based on Moscow’s control over natural resources, its global reach and a musclebound nuclear-backed military, but also on Putin’s confidence that he can out-shout and outwit his adversaries with a growing network of allies. Now it turns out these allies have been hollowed out by what the hawk-eyed historian Anne Applebaum calls metastasising kleptocracy. And, since that rot has taken root in the quarter century of Putin’s rule, it has become clear that Mother Russia is as rotten as its hangers-on.

All imperial constructs follow a similar pattern of decay. Western Rome fell because of military losses to the Goths on the boundaries of empire, the financial crisis stemming from war spending, labour shortages, the neglect of civil infrastructure at home and the brutalisation of captive territories. The Habsburg empire too began to unravel at its mismanaged peripheries, with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914. Putin is the very embodiment of imperial overstretch.

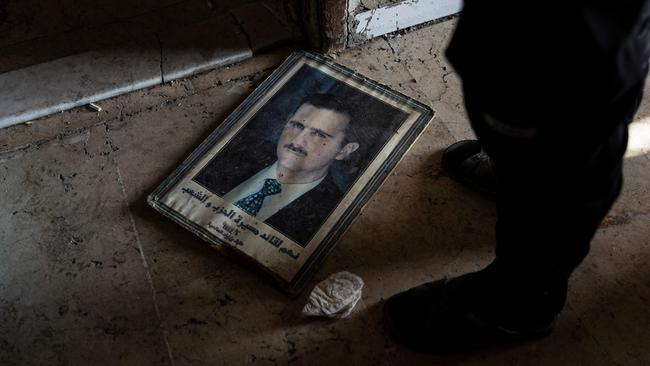

There is then a very practical question to be addressed. Does the implosion of the Assad regime (and the dictator’s expensively negotiated flight to Moscow) provide a pointer to the future of his Kremlin patron? The conversation is no longer about Putin’s strategic ambition - expanding Russia’s hold on the rare mineral exploitation of Africa, the coming dismemberment of Europe’s security apparatus, its central role in politically exploiting the melting Arctic or the impact of the Russian-Chinese duopoly on Earth and in space as the new US administration withdraws into a geopolitical shell. No, the pressing issue is: who is next on the redundancy list after Assad, and how quickly will Putin’s protective layers be peeled away?

One bet is on the galloping self-destruction of Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus, in power since 1994. He is already gearing up for another sham presidential election at the end of January. During the last such election in August 2020, 18 months before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Moscow advised its ally on how to squash protests. This time round, opposition leaders in Belarus are urging their supporters to bide their time: the anti-Putin, anti-Lukashenko chemistry is likely to be different and will need strategic guidance that is difficult to deliver from a prison cell. For the Minsk regime, much will depend on the terms on which the Ukraine war can be ended - if Putin is depicted by his domestic ultranationalist critics as having struck a weak deal with the West, then he may have to signal strength in other ways by making the infrastructure in both Russia and Belarus even more vicious.

So far, Lukashenko has survived by closely studying Putin, anticipating the Kremlin reaction to external and internal challenges. No crack team of CIA analysts tracks Putin as closely as his supposedly closest ally in Minsk. But will Lukashenko still be able to count on Moscow’s support in a crisis? Or will he soon be inhabiting a sterile high-rise apartment alongside the Assad family, living off his squirrelled-away fortune? The disgraced Ukrainian leader Viktor Yanukovych already lives in Moscow’s posh suburb of Rublyovka (Putin put him on standby to resume the Ukrainian presidency after launching the unsuccessful February 2022 attack on Kyiv.) More will be on the way in 2025. Increasingly desperate Nicolas Maduro of Venezuela, perhaps? Russia’s imperial hub is beginning to resemble an upmarket version of EastEnders, with its blood feuds and bust-ups in the boozer.

Joining the show in the coming year could be some of the leaders of the pro-Kremlin Georgian Dream party, whose slavish adherence to Putin’s playbook has set the country alight.

After allegedly rigging elections in October, says the Georgian film-maker Anna Japaridze, “it felt like we were sleepwalking into becoming a Russian vassal state ... [the government] announced that Georgia’s EU integration talks would be suspended until 2028, in a country where public support for joining the bloc has polled around 80 per cent”. As a result, she says, “the mood suddenly shifted. People were no longer defeated, they were furious.” The outgoing president Salome Zurabishvili still refuses to concede defeat and joined the new year street protests against the manipulated election. The Georgian Dream machine rolled on regardless, with its chosen candidate, the ex-Manchester City striker Mikheil Kavelashvili, being sworn in as president. The result: a deeply polarised state. Putin counts that as a win.

The revolt on the Russian periphery triggers fury, from the Kremlin upset about ungrateful allies and from oppressed neighbours who fear they are being bulldozed into conformity. Putin’s position weakens by the day. That has real strategic consequences. Since Ukrainians have been using western cruise missiles to drive Russia’s Black Sea fleet out of the Crimean peninsula, Putin’s naval commanders have been looking to expand the port of Ochamchire in the Russian-occupied Georgian territory of Abkhazia. Satellite images show this project is advancing quickly. The risk of the Putin ploy: that the Ukrainian war spreads to Georgia. Also part of his strategic calculation: a big Russian naval presence on Georgian soil will make Nato think twice about extending alliance membership to the Georgians. Abkhazia and South Ossetia, both frozen conflicts since 2008 when Moscow snatched the territories, risk coming back into play, new battlegrounds in a desperate never-ending war against the West. Rational behaviour for a leader who wants calm and docile neighbours on his borders? Not really. And that is why his authority is crumbling.

Putin has shown he is not afraid of stirring up trouble to unsettle Europe or control sea lanes considered important for Russian security. But the long wheezing battle against Ukraine is rallying Putin’s unhappy neighbours. So far they have mostly ducked out of making a choice between Putin and Kyiv. Now leaders are using varying methods to distance themselves from Putin. At a summit in Astana, attended by Putin, the Kazakh president Kassym-Jomart Tokayev addressed leaders in the Kazakh language, not Russian. His point: the Soviet Union no longer exists and we don’t have to dance around the man from Moscow.

Meanwhile, Armenia, once a loyal (and dependent) ally of Russia, has let it be known it does not want to stay in the Russia-dominated Collective Security Treaty Organisation: it was disappointed by Putin’s lack of support in a brief unsuccessful war with Azerbaijan over the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh. The Armenian premier, Nikol Pashinyan, was blunt about it: “Moscow has been unable to deliver and is in the process of winding down its role in the wider South Caucasus region.”

That’s more than a sigh of impatience about Moscow’s long, distracting war against Ukraine. It’s a sense that Putin himself is abdicating from some of his key beliefs - that the dissolution of the Soviet Union was an epochal disaster and that he considered it his sacred duty to be the security anchor of post-Soviet states. It was Putin who sneered at Joe Biden’s clumsily executed US withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021: a clear signal, he suggested, that America was in decline, unable to defend its allies or its values over the long haul. That was a bit of point-scoring. But it also concealed a source of Putin’s self-doubt. In 1989 he was still a KGB officer based in Dresden in communist East Germany. That was the year when communist regimes collapsed like dominos across eastern Europe. It was the year when Soviet forces finally withdrew from Afghanistan, the first time a superpower had been defeated by a radical Islamic group. It was the year when Chinese communist authorities demonstrated resolve and held on to power by slaughtering protesters in Tiananmen Square. And 1989 ended for Putin with the collapse of the Berlin Wall, the burning of sensitive files in the Soviet consulate, and the return to a dispirited Soviet Union which already seemed to be in its death throes.

Although 2024 wasn’t quite that dramatic, there are enough whispering echoes from that year of collapse to rattle those around Putin. The central question in 1989 was how can you reform and still retain control? Now the Putin years have reframed that rather academic question (answer: you enrich loyalists and pretend to reform) into how can Russia recover its greatness and command global respect? If Putin stays true to form he will push for the retention of Russian bases in Syria as a nod to global clout but will go all-out for victory in Ukraine. “If he thinks the fate of the world is being decided in the Donbas,” says Aleksandr Baunov of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia group, “then the future of Syria will be decided there as well.”

Putin has persuaded fellow members of his Axis of Doom that Ukraine is a civilisational struggle against malign western encroachment, which is exposing American arrogance, not Russian decline. North Korea’s Kim Jong-un would not have sent weapons and men into Putin’s battle if he thought the Russians were going to lose. Kim is offering Putin his soldiers as human tribute. Their lives, he may calculate, are cheap compared with the potential rewards that will be bestowed on North Korea should the Russians win out. It’s a reminder of how Moscow used to hint to its allies that an act of solidarity towards a nuclear-armed state can go a long way. A wise investment in uncertain times.

But outside the killing fields of Ukraine, Putin is now largely missing in action. Russia saved Assad by bombing Aleppo in 2015 but there has been no follow-through by, for example, training Assad’s army. Russian military academies teach future officers the exemplary use of air power in flattening rebels but the most significant presence in Syria for the past few years has been military intelligence spying on Turks in the north, on Israeli strikes against Iranian units in Syria, and on the tensions between Bashar al-Assad and his brother Maher. Putin could have done more to shield Assad from his hopeless decisions but chose not to.

Ultranationalists in Russia are already calling Syria “our catastrophe”. And Russian military analysts are being remarkably free-spoken about Moscow’s failings in Syria as a cloaked way of criticising the war in Ukraine. “In a modern world, victory is only possible in a fast and short war,” wrote the military commentator Ruslan Pukhov the other day in an article that certainly reflects a prominent strand of thinking in the general staff.

The Syrian civil war has been raging, on and off, for 13 years. The Ukraine incursion is about to enter its fourth year. Putin, the generals might be thinking now, doesn’t really understand the concept of victory. This will be important for Donald Trump to understand after he enters the White House and broods on how to end the war in Ukraine. He will be dealing with a more wounded and lonelier Putin than in his first term. It is easy enough to make the point to Putin that the war has become an act of self-harm for him. Why lose an empire (even a wobbly one) for a chunk of forsaken land in Donbas?

War has blindsided the Russian leader. His poor management and eventual elimination of the Wagner mercenary boss Yevgeny Prigozhin took away the ability of Russian contractors to work in and out of Syria; also the profitable underside of opportunistic war – the arms trafficking, the gold smuggling, the bodyguarding of key figures from Sudan to Mali, from Niger to Latakia. Putin and his intelligence chiefs failed to see how Israel was depleting Iran in Syria. Russian air-traffic controllers looked the other way when Israel struck at Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps targets. The result: not only the humiliation of Assad but also the deep distrust of the Iranians. And Putin has underestimated Turkey’s President Erdogan who outplayed him in the ousting of Assad.

So, of course, Putin has not only lost allies, he has burnt his boats in the global south, in countries whose rare metals and minerals he craves as part of his pretension to be a superpower leader. The score sheet from the war on Ukraine does not flatter him. Parts of the Russian region of Kursk are still occupied by Ukrainian troops, the Black Sea fleet has been hit hard, Donbas has been flattened, hundreds and thousands of Russian soldiers have been killed and seriously wounded, the shift to a war economy has aggravated labour shortages and inflation, bankruptcies are on the increase. If Putin was brave enough to leave the Kremlin on foot, he would see scenes similar to those he witnessed when he returned to Russia from Dresden in 1989: unaffordable prices, limbless veterans.

Putin, it is clear, should get out of the war business. He’s no good at it. Is Donald Trump the right man to deliver that message? Probably not - he can barely hide his eagerness to pick up the Nobel peace prize in 2025 and could therefore be easily hoodwinked. He is dealing with a man who in his memoirs described the life lessons he learnt when cornering a desperate rat in his St Petersburg apartment block. Perhaps Trump could try some plain-speaking instead of oily flattery when they meet again face to face. You are the rat now, he could say, and this is my stick.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout