Princess Marianne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn, dead at 105, was a top shot among the international smart set

Whenever Princess Marianne found herself in high society, she would unclasp her Chanel handbag to retrieve a small camera and begin to snap. She has died aged 105.

Whenever Princess Marianne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn found herself in high society, which was often, she would unclasp her Chanel handbag to retrieve a small camera that she kept hidden there “like lipstick” and begin to snap.

She knew most of her subjects already – she said she “always photographed her friends as friends” – so they were instinctively at ease. The photographs she took, about 300,000, were masterpieces in candid, sometimes comic, intimacy: Aristotle Onassis attempting to repair his beach car; or soprano Maria Callas snorkelling with her poodle on her back. “You’re not a paparazzo,” Princess Caroline of Monaco once said. “You’re a mamarazza.”

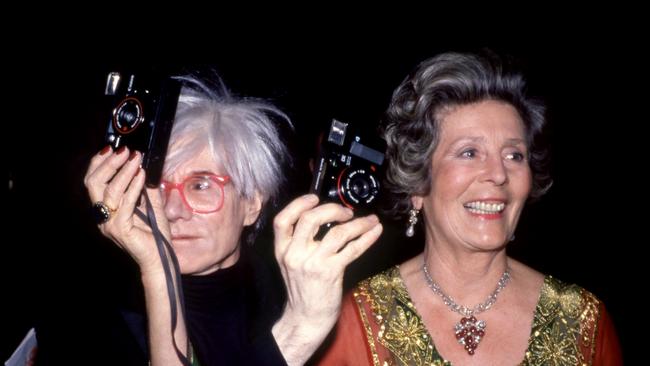

She photographed her children – in one, her daughter memorably swigs sherry and her son puffs on a cigarette – and her children’s children, but she also captured world leaders, celebrities (including Andy Warhol) and royals.

When asked by German magazine Bunte to photograph King Juan Carlos of Spain and his wife, Marianne failed to mention she knew the couple. At the palace, she was placed at the back of a swarm of press photographers and television crew because of her height.

Then the royal couple arrived. “Suddenly, Juan Carlos looked up and said, ‘Manni, what are you doing here?’ I went to the front and curtsied – with all my cameras dangling – and told him that I was on assignment. He called over to the queen and said, ‘Sofi, come see, Manni is a professional!’ ” She was invited to have tea in private afterwards and take more candid shots.

What drove her was a restless interest in people. “The day is too short for me because of my curiosity,” she said. “When I wake up, I always think, ‘Who will I meet? What will I hear?’ ”

At the age of 80 Marianne would publish a book of her photographs, Mamarazza. “I had been talking with several publishers in Munich, but their ideas were completely stupid,” she said. “Then I called Karl Lagerfeld, who is a friend of mine. I asked him where he publishes his books. He said, ‘What a question! With Steidl.’ ”

For two months she pored over 300 albums compiled across a half-century, putting the book together with the help of assistants. “The very first day, I said to Mr Steidl, ‘Now, it’s one o’clock. I’m leaving. I want to eat spaghetti and drink a glass of wine.’ He looked at me and said, ‘You will stay here like all the others. We can’t work if everybody runs off eating.’ ”

Maria Anna Mayr von Melnhof was born in 1919, the eldest of eight children of Baron Mayr-Melnhof and Maria Anna, countess of Meran, a descendant of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II.

Her upbringing, in a fairytale castle called Glanegg, was strict: the children had two dirndls (an Alpine dress) for summer and two loden skirts for winter. Their father forbade “the brats” a chauffeur, insisting they cycle to school.

While a student at the Blocherer art school in Munich, she met Prince Ludwig Furst zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn, or Udi, a German royal on leave from the war.

When they married in 1942, her mother moved her to cookery school, and when he returned to fight she stayed in Salzburg with their two children, moving west to Bavaria as the Russians advanced eastwards. Soon, news came that Udi was missing in action.

In reality, he was a prisoner of war in England and the couple were reunited in Salzburg in 1946. “I left the children in Salzburg with my parents, and Udi and I took a freight train to West Germany. It was the middle of winter and bitterly cold, but a friend had given us a small coal stove to keep us warm. It saved us.”

As the German soldiers retreated, they had blown up Sayn, and the couple found the 12th-century castle in ruins. Given a room by a priest, they spent the next few years growing vegetables and flowers to sell in the market, in the evenings changing into evening dress “made out of carpets” and driving to Bonn, the capital, to dine with old diplomat friends.

“I remember once, I walked home along the railroad tracks in the snow and found 14 briquettes of coal. Oh, they seemed like gold. Tears came when I saw them,” she said.

In 1958, Udi succeeded his father, Gustav Alexander, as the sixth prince of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn. Four years later, aged 43, he was found dead on a sidewalk close to their home after being hit by a drunken truck driver.

Left “almost bankrupt”, Marianne moved back to her home in Salzburg and began selling her pictures to gossip magazines.

Luncheons she hosted became famous for their glittering guests, including Margaret Thatcher. “I met her one morning nearby in St Gilgen. I said, ‘I live right over the hill and I have a little shooting lodge. I’m having a luncheon today and I would be delighted if you could come.’ She thanked me but said it was impossible because of her schedule.

Then, as an afterthought, I said, ‘How sad. I believe Sean Connery will be coming.’ She said, ‘You mean James Bond?’ ” Marianne drove home, where she had 30 guests waiting. An hour later, a black limousine pulled up and Thatcher’s bodyguards “swarmed out into the woods”.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout