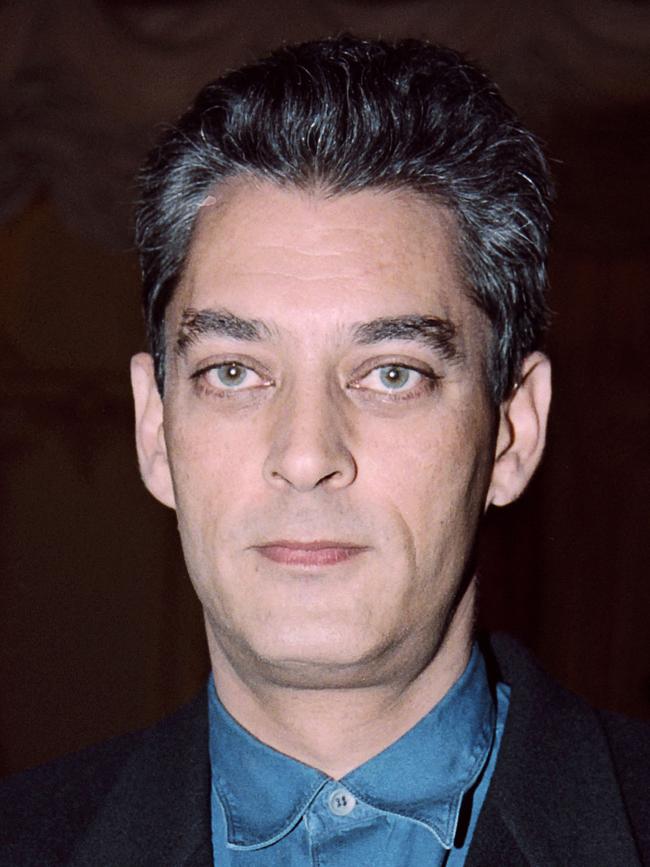

Paul Auster obituary: flamboyant writer who mixed autobiography and fiction

Paul Auster, a charismatic novelist, memoirist and screenwriter, was lauded for his postmodernist fiction, most famously The New York Trilogy.

OBITUARY

Paul Auster, author.

Born in New Jersey, February 3, 1947. Died in New York City, April 30, aged 77.

Paul Auster attended a summer camp at the age of 14 that changed his life. A storm erupted while the group was in the woods, prompting campers to hurry towards a clearing by crawling under a barbed-wire fence. Lightning struck the fence as the boy in front of Auster was climbing through, killing him instantly.

Auster, who sat beside the corpse for an hour, had escaped death by a few seconds, a few centimetres. “I’ve always been haunted by what happened, the utter randomness of it,” he told an interviewer. “I think it was the most important day of my life.”

It was hardly surprising that mortality, chance and destiny became prominent themes in Auster’s large body of work.

A young character meets a similarly abrupt demise in his novel, 4 3 2 1, a weighty study of fate and, as the last chapter puts it, “the endlessly forking paths a person must confront”, via the conceit of imagining a protagonist leading four parallel lives. It was shortlisted for the 2017 Booker Prize, three decades after Auster found international fame with The New York Trilogy of postmodern detective novels.

The first, City of Glass, was rejected by 17 publishers before finally making it into print in 1985, when Auster was 38. It was inspired by a wrong number: Auster took a call from someone trying to reach the Pinkerton detective agency. “We are continually shaped by the forces of coincidence,” he told The New York Times in 1995. “Our lifelong certainties about the world can be demolished in a single second. People who don’t like my work say that the connections seem too arbitrary. But that’s how life is.”

Last year he published a searing indictment of American gun culture, Bloodbath Nation, that drew on a shocking piece of family history. As a child, Auster was told his grandfather had died in an accident. He learnt the truth from a cousin who struck up a conversation with a stranger during a flight in 1970. The passenger happened to know the real story: Auster’s grandfather was shot dead in 1919 by his estranged wife, Auster’s grandmother.

She was acquitted on grounds of temporary insanity and moved her five children from Wisconsin to New Jersey, ultimately giving Auster easy access to New York, the city that would influence him profoundly. But, Auster wrote, his father – six years old and upstairs when the shots rang out in the kitchen – grew up to be “subdued … lonely, fractured”.

More cheerfully, Auster adopted a dog after a random encounter with its then owner, a woman he met in a park, and the event informed his 1999 novel, Timbuktu, written from the perspective of Mr Bones, a mutt whose master is dying.

Auster was especially celebrated in France. In 2009, a New Yorker writer termed Auster “probably America’s best-known postmodern novelist”, a status he found difficult to digest. “I must have over 40 books about myself in the house,” he told a reporter in 2012. “It’s all so strange.”

He was boldly unconventional – a 2012 memoir, Winter Journal, was written in the second person, and a reviewer judged it “a work that is often startlingly good in parts but, as a whole, seems deranged”. And to his critics the flamboyance could appear gratuitously theatrical and burdened with cliches.

One commentator decried a “general B-movie atmosphere” in his work. But few would deny his books were highly readable and inventive, although the crisp prose of his early years yielded to a more baroque style as he aged and his plot mechanisms became formulaic.

Mixing autobiography and fiction, toying with form and sprinkling literary references, Auster, who lived in France as a young man, married Parisian verve and intellectualism with a grasp of American belligerence and a relish for the cosmopolitan vitality of New York. He oscillated dizzyingly and dazzlingly between highbrow and lowbrow. “If the avant-garde gestures bore you,” one reviewer observed, “a gunshot will soon ring out, or some unfortunate will have his brains bashed in with a baseball bat.”

Paul Benjamin Auster was born into a Jewish family in Newark, New Jersey, in 1947, to Samuel, a property landlord, and Queenie (nee Bogat), an interior decorator who regretted the marriage as soon as the honeymoon. They divorced when Paul was a teenager.

Samuel had no interest in books but an uncle, Allen Mandelbaum, was a distinguished scholar and translator. He went to Italy and left boxes of books in storage at the Auster house, providing the young Paul with a ready-made library. He also devoured the Sherlock Holmes stories and the complete works of Edgar Allan Poe.

After high school in the New Jersey suburbs, Auster toured Europe before studying English and comparative literature at Columbia University in New York. At university, he told The Guardian in 2002, he read “like a demon. Really, I think every idea I have came to me in those years. I don’t think I’ve had a new idea since I was 20.”

Incapable of holding down an ordinary office job after graduation, he invented a baseball-themed card game, worked as a census taker and on an oil tanker, writing poetry in his spare time before moving to Paris in 1971. There he met one of his idols, Samuel Beckett; had a stint as a night-time switchboard operator for a New York Times bureau; and translated the North Vietnamese constitution from French into English. He became caretaker of a farmhouse in Provence with his future wife, Lydia Davis, a writer and translator.

They returned to New York and married in 1974 but he struggled to make a living as a poet and translator, and felt miserable. Inheritance money after the sudden death of his father – he had a heart attack while making love – allowed him to focus on writing. Auster went on to produce more than four dozen published novels, works of nonfiction, collections of poetry, screenplays and translations from French. His books enjoyed such cult status among impoverished young intellectuals that they were frequently stolen from shops, forcing booksellers to lock them in a cupboard.

His first success, The Invention of Solitude (1982), examined the writing process and his distant relationship with his father. The Music of Chance, about a fireman who picks up a hitchhiker who is a professional gambler, became a film; Mr Vertigo, about a levitating boy who joins a circus, led to a friendship with magician David Blaine.

A screenplay that the cigar-puffing Auster wrote about the manager and customers of a Brooklyn tobacco shop was made into an acclaimed independent film in 1995: Smoke, starring Harvey Keitel and William Hurt. (Auster credited his cigar habit with producing his husky voice, which was “like a piece of sandpaper scraping over a dry roof shingle”, he said. Ill health in his later years made him turn to vaping.) A mostly improvised sequel, Blue in the Face, co-directed by Auster and Wayne Wang, featured Madonna, Michael J Fox, Roseanne Barr and Lou Reed.

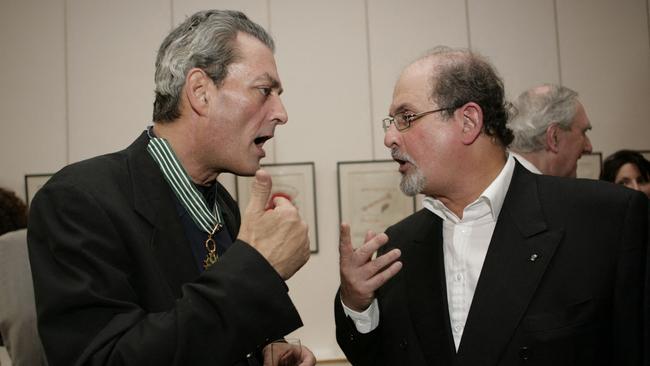

Less admired was Lulu on the Bridge, an abstruse 1998 romantic drama he wrote and directed that was a critical and commercial flop. A plan to cast his friend Salman Rushdie, the author under a fatwa, was scuppered after some of the crew objected on security grounds.

Reviewers were also undelighted by The Inner Life of Martin Frost, a 2007 mystery starring David Thewlis that Auster wrote and directed. The previous year he won a Prince of Asturias Award “for the transformation in literature that he has wrought by blending the best of American and European traditions”.

Drafting by hand then typing up the pages on a venerable typewriter, the habitually black-clad Auster toiled steadily in a plain studio lit by bare bulbs. He described the space as “unkempt and unattractive” as he was so rapt in his work that he had no interest in his surroundings. For him writing was “often wrenching, difficult and painful”, but he persevered “because it makes you feel you’re living to the limit of your possibilities”. At the end of the day he walked back to his house in Brooklyn to slump in front of the television and watch classic films or baseball.

The union with Davis ended in divorce but produced a son, Daniel. A DJ and photographer, he was a drug addict and died of an overdose in 2022, 11 days after being charged in relation to the death of his ten-month-old daughter, Ruby, who had ingested heroin and fentanyl. Auster remarried in 1982, to the novelist Siri Hustvedt, after they met at a poetry reading. “She resurrected me from the dead,” he said. They had a daughter, Sophie, a singer-songwriter.

A committed left-winger, he gave an interview to a Turkish newspaper that ignited a war of words with the nation’s prime minister in 2012. Auster said he would not visit Turkey or China in protest at their imprisonment of journalists and writers. Recep Tayyip Erdogan countered: “As if we need you! Who cares if you come or not?”

Later in the decade, Auster aimed his ire at Donald Trump. The improbable political rise of the real-estate mogul was, Auster asserted to the Financial Times in 2017, more evidence of the philosophy animating his life and work. We should, he said, “understand the world as an unstable, unpredictable place, not insist that it’s an exception every time we see it happen. This is how things work.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout