Oxford lab claims early lead in race to find vaccine

Top scientists give their verdicts on COVID-19 vaccine candidates as an Oxford University team offer hope — and raise eyebrows among virologists and researchers.

Compared with the pharmaceutical giants that dominate global drug manufacture, the Oxford research laboratory named after the 18th-century Gloucestershire physician who created the world’s first vaccine appears a minnow.

Yet it was Oxford University’s world-renowned Edward Jenner Institute for Vaccine Research that sounded the most optimistic note last week while mega-corporations such as Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer were warning of long and difficult development and testing processes ahead.

The Oxford team’s claim on Saturday that a vaccine might be ready by September raised eyebrows among many virologists and researchers wary of overpromising a reliable solution to the coronavirus crisis.

Some virologists are already wondering if a COVID-19 vaccine will prove as elusive and frustrating as the search for an HIV vaccine, which has been going on for more than 30 years. What is the reality of the current effort? Last week some of Europe’s leading experts on infectious disease talked of the challenges of guiding any new vaccine from laboratory promise to mass protection.

What is Oxford up to?

Many vaccines take years, if not decades, to develop. But British science has come a long way since Jenner realised in the 1790s that a bovine disease then known as cowpox could help to protect humans from smallpox.

At the institute that honours his discovery of a working smallpox vaccine, they were able to get started on January 10, the day Chinese doctors published the genome sequence – the entire DNA structure – of the novel coronavirus.

“This was Disease X,” said Sarah Gilbert, professor of vaccinology at the Jenner Institute. “This was the unknown disease for which we’d been preparing. When we saw Disease X arising, we thought: let’s give it a try. Let’s see how quickly we can make a vaccine.”

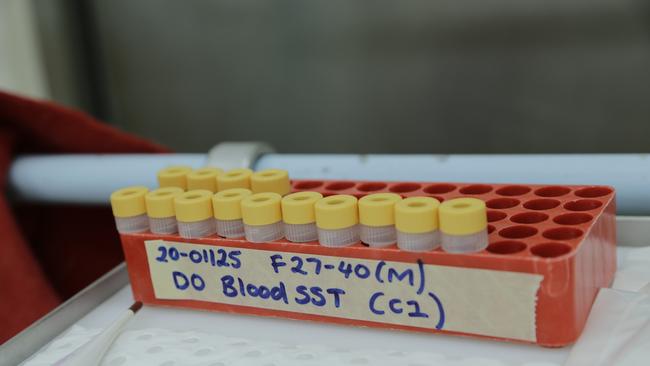

The team has recruited a group of 510 volunteers to test the vaccine it has modified from its “Disease X” template. Gilbert is optimistic that she will know within six months if her product is safe and effective.

What could go wrong?

The Oxford vaccine, known to its creators as ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, has joined an extraordinary international race to find a long-term solution to the coronavirus threat. The World Health Organisation has identified 44 “candidate” vaccines undergoing clinical evaluation in 14 countries. At least two are already in the first phase of human trials.

“The level of effort going into vaccine development today is unprecedented and encouraging,” said Professor Robin May, a virologist at Birmingham University.

“The galvanising of the research community makes me optimistic that we will hit on a successful strategy eventually. But there are some questions about the virus we just can’t answer yet and that will have a bearing on the safety and efficacity of any new vaccine.”

What are the main obstacles?

Not the least of the problems faced by countries in lockdown is the prospect that extreme social distancing measures might make it hard to establish whether the vaccine or the lockdown is the most important factor in keeping volunteers healthy.

“Obviously a successful lockdown is a very good thing for the country, but if it means we can’t tell if the vaccine works, we would have to do a trial in another country where there is more transmission,” Gilbert said.

May, who discovered as a student that he “really liked microscopes and the things we can’t see that live in us or on us all the time”, cautioned that in the case of COVID-19 there are big questions that we still cannot answer.

These include: how strong is the immunity conferred on those who have survived infection and how long it might last. Nor can we yet tell if the virus now known to researchers as Sars-CoV-2 is likely to mutate as it spreads, making it more difficult for the original antibodies to detect and attack it.

Once the immunology is sorted, clinical testing must primarily be geared towards safety. “Yes, we want to know you’re going to get a good immune response, but we also want to know you’re not going to get massively sick,” said May. “And then we’ve got to start producing it in very large numbers because we will need a huge amount of doses. None of this is easy.”

What are the main dangers of rushing?

The history of vaccine research is littered with examples of promising candidates that fell along the way. Four decades after the virus that causes Aids ripped through San Francisco and New York, there is still no HIV vaccine.

“There was a quite promising vaccine that did not succeed in clinical trials,” said May. “HIV also has an astronomical mutation rate – the virus that comes in is not the same a few months later. You end up with the vaccine you targeted not recognising its target any more.”

In the case of dengue, a viral infection spread by mosquitoes, a vaccine that was successful in some patients made others feel more ill.

Coronaviruses behave more conventionally and researchers are still hopeful that COVID-19 will not mutate so rapidly that a vaccine cannot target it.

Not the least of the unknowns is how a successful vaccine will be administered. “Will a single injection be sufficient or will it require boosters?” May said. “There are very different routes to scaling up production of different types of vaccine and the landscape changes dramatically if boosters are needed.”

What do other vaccine hunters think?

Paul Stoffels, chief scientific officer at Johnson & Johnson, said that his company has successfully tested a candidate vaccine in mice but will not start testing on humans until September.

The company will not know whether its vaccine is safe until early next year. Mikael Dolsten, Stoffels’s counterpart at Pfizer, said the firm was developing a vaccine with a German company, BioNTech, and hoped to turn “months to weeks, weeks to days and days to hours” in attempting to deliver millions of doses by the end of this year.

In the past, Dolsten told the health website Stat, he had compared drug development to a game of chess, where scientists plot a careful strategy of moves in advance. But a vaccine for the coronavirus was more like backgammon, he said. To win at backgammon, you have to roll the dice and then hope for some luck.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout