Offered war, prison or a bullet, Russians choose to desert

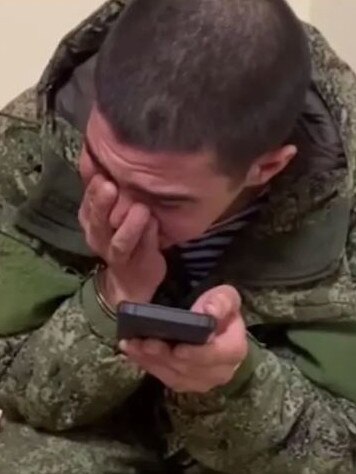

Thousands of terrified and untrained troops are contacting a Ukrainian hotline for deserters and being guided to safety by the ‘enemy’.

On the morning of May 9, as President Vladimir Putin’s generals polished their medals for the Victory Day parade in Moscow, a Russian soldier called Ruslan cowered in a trench outside Bakhmut, surrounded by death.

Above him a Ukrainian drone hovered, while behind him Russian mortars prepared to strike if he dared fall back. His options were to fight, flee or surrender, and only one did not lead to oblivion.

Ruslan’s next steps became a public relations coup for the Ukrainians. A video that has been shared around the world shows how the Russian signalled to the drone not to shoot and was led across no man’s land to the Ukrainian lines.

While the circumstances of Ruslan’s deliverance are unusual, he is not alone in breaking ranks to flee the chaotic and murderous Russian war machine.

The Ukrainian “I Want to Live” hotline, for Russian soldiers wishing to surrender, was contacted 3,174 times in April, a 10 per cent increase on the previous month.

After getting in touch on their own phones, willing Russians are encouraged to stay in touch using a burner phone “with buttons” - one that isn’t a smartphone - so they can’t be tracked as they are guided by a Ukrainian operator, and in some cases a drone, on the perilous journey to enemy lines.

Desertion is also on the rise.

Official Russian government data shows more court cases have been opened against soldiers for abandoning their unit so far this year, 1,053 cases, than in all of last year (1,001).

Meanwhile, brave volunteers, risking imprisonment by scouring social media posts and the graveyards of Siberia, are collating a picture of the Russian dead that is more accurate than ever before.

The names of 23,256 fatalities have been collated by the poteru.net project, a number that rises with each hour and is likely to be a fraction of the true figure.

What is life like for a Russian soldier? Is it love for the motherland, coercion or cash that drives them to die in the Donbas mud?

As a former prison officer in one of Russia’s brutal penal colonies, Ruslan said he was mobilised in September alongside 300,000 compatriots.

“For Ruslan, the choice was prison or war,” said Vladimir Osechkin, a Russian human rights campaigner who spoke to the soldier in Ukrainian custody this month and posted the interview on YouTube. Osechkin, who lives under permanent police protection in France, has previously faced criticism from Ukrainians after helping a former Wagner mercenary, Andrey Medvedev, flee to safety in Norway. Ten days ago Medvedev announced he wanted to return to Russia, despite the risk of death.

Interviewing a prisoner of war is a grey area within the Geneva conventions, which protect captured soldiers from being turned into subjects of “public curiosity”. The extent to which anybody in captivity can truly speak freely is open to question and disclosing their identities can also expose them to danger if and when they return home.

Ruslan’s account, while it may be unreliable, is, however, a potentially rare insight into the final moments of those who will never be able to tell their story.

Check out our latest feature in the @Telegraph! 🇬🇧ðŸ¤ðŸ‡ºðŸ‡¦https://t.co/xy1N4pcRcE

— Vans Without Borders 🇬🇧🇺🇦 (@vansnoborders) May 20, 2023

He was enlisted as a gefrietor, the equivalent of a corporal in a motor rifle division. On arrival in Ukraine he was told the division would act as a form of military police keeping order among Russian forces, but in early May he was told they were to travel to Bakhmut to replace Wagner Group mercenaries leaving their positions outside the town.

On May 8, Ruslan arrived outside the town in a troop transport - where, to his surprise, he and three fellow soldiers were handed over to the charge of a Wagner fighter, who sent them over the top to secure a trench.

“If you fall behind, I will annihilate you. If you refuse to fight, I will annihilate you,” the man said. ” ‘If you are caught in fire on the way, no one will drag you out, we will just finish you off.’ That’s how they escorted us to our positions,” recalls Ruslan in the interview. He and the two other newcomers spent hours in a trench lined with up to 40 bodies of Ukrainian and Wagner troops. A mortar barrage wounded all three, but no one replied when they radioed for help. One of the men had both legs broken by a Ukrainian drone. He is thought to have shot himself soon afterwards, knowing that no one would drag him out.

Ruslan found a foxhole. The third man sprinted past him, along the trench searching for cover, pursued by the drone. “There was an explosion, it caught him on his spine, he fell immediately, right in front of my eyes. He was alive but he couldn’t move his legs,” Ruslan said.

Moments later the man reached for his own grenade, whispered, “Brother, I feel bad”, and pulled the pin. “At that point I thought, I might as well give them a sign, the drone operator will by any case be a human,” he said.

A growing number of Russian conscripts, faced with the reality of the war, are trying to save themselves before they reach the trenches.

The organisation Go by the Forest, set up by a former St Petersburg activist, Grigory Sverdlin, helps Russian men who do not want to fight to go off-grid or leave the country to dodge the draft. They have given advice to nearly 10,000 men since September, of whom roughly 10 per cent are deserters. “There’s definitely an increase compared with autumn. Now the flow [of deserters] is definitely larger,” said Anton Gorbatsevich who himself fled after being called up to fight, but now helps others escape.

He is part of a network of volunteers in neighbouring countries that help deserters trek across the steppe or through the forest to dodge border points.

The best time to desert is when they are wounded at a military hospital, according to Gorbatsevich.

“Doctors get soldiers to sign blank check-out forms so if they run away, the doctor can fill in the rest, with dates, so it looks like they have discharged them - therefore the responsibility would lie with the military unit and not with the doctors,” he said. A soldier has two days to leave the country after going Awol while a criminal case is lodged.

Dmitry, 27, a former officer who is in an undisclosed location, fled his military base in western Russia around February 23, a national public holiday, giving him an extra 48 hours before anyone would start looking.

In February, he was told he would be sent to the front. “I understood, that’s it. I can’t refuse. They are sending me [to war]. If I refuse, they send me to prison. If I go to prison, I’ll be sent to the Wagner Group. There is no way out,” he told me. Dmitry joined the army last summer following his graduation, having agreed in 2016 to serve after university as a way of securing accommodation in student halls in Moscow.

He recalls mobilised troops being sent to his unit last winter but no one engaged with them or gave them any training before they were sent to war.

“Even the authorities in my unit did nothing with them, they just gave them a tent, a gun and a mat to sleep on and that was that,” he said. Men from the ages of 20 to 60 slept in the grounds of the base, in tents, in midwinter.

What awaited them was well known to the officers, of whom between ten and 15 had fought near Kharkiv at the start of the war. “They said no one needs to go back there, no one needs it. It’s not at all like they say it is on television,” said Dmitry.

The returning officers, almost all of whom had been wounded, complained of having to loot and steal because no one gave them clothing or food. But according to Dmitry there was little remorse about the effect this would have had on the local population. “They didn’t feel guilty about it. I don’t know why. Maybe because the propaganda machine works so well, the idea that they’re all Nazis and so on, maybe they’re not clever enough to understand simple things.”

Russian forces have committed widely documented war crimes in Ukraine, from the rape and murder of civilians to the summary murders of prisoners of war.

“Soldiers committed crimes there every day,” said Alexander, 25, a lieutenant in a signals regiment who served in southern Ukraine last summer, before deserting. He recalls seeing 12 Ukrainian prisoners of war dead on the side of the road. “They were in a seated position, some were standing but had fallen, all of them had their hands tied behind their back,” he said, “It’s hard to explain my emotions at that time. I felt for them but at that moment my primary task was to survive.”

The glory of dying for Mother Russia is drummed into children at a young age.

Since the Soviet period, schools across the country have devoted “hero desks” at the front of each classroom to a fallen soldier, details of their podvig - “great deed” - is written on the wood.

Sitting at a hero desk is a great privilege awarded only to the best students. The death toll from the war in Ukraine is a state secret but the number of desks has been multiplying.

“These ‘great deeds’ are of course made up,” said Mikhail Stepanov, a Russian emigre in the US, who is attempting to catalogue the war dead alongside a team of volunteers in Russia who risk imprisonment for helping him.

“I feel terrible when I see this propaganda working among children as young as six or even younger, it reminds me of fascist Germany,” said Stepanov. “If, God forbid, this war drags on for years, then many of these children will go to fight too.”

But the solemn ceremonies for unveiling these new desks, and the social media posts accompanying them, is one of the ways that Stepanov’s team are uncovering the scale of the dead. In the run-up to Victory Day there was a surge in names posted on social media. Stepanov went from cataloguing about 500 deaths a week in January to almost 2,000 a week.

Families of dead soldiers are owed compensation of seven million roubles, around pounds $133,000, a huge sum in rural Russia. But if no corpse returns, no money is paid. There have been reports of incinerators behind the front line cremating piles of bodies.

Even those who receive a coffin, often get them six or seven months after the soldier died: deeply painful for an Orthodox Christian or a Muslim family - for whom a quick burial is customary.

In several weeks, the families of the soldiers who died on the morning of Victory Day will discover they are “missing in action”. But, according to Russian campaigners, they are unlikely to ever receive their remains.

Ruslan has spoken about his wife and daughter since his brush with death. “While there is time I want to tell [them] that I really love them, and that I really want to return to them,” he said.

From the men who died in the trench alongside him though, there was no message home, just silence from the mud outside Bakhmut.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout