Nuclear fusion breakthrough smashes world record

For five seconds one day last December the hottest place in the solar system lay just south of Oxford.

It was just five seconds. It was just a prototype.

But for that short period of time, one day last December, the hottest place in the solar system lay just south of Oxford. And in that place, a 25-year-old record in fusion energy was broken.

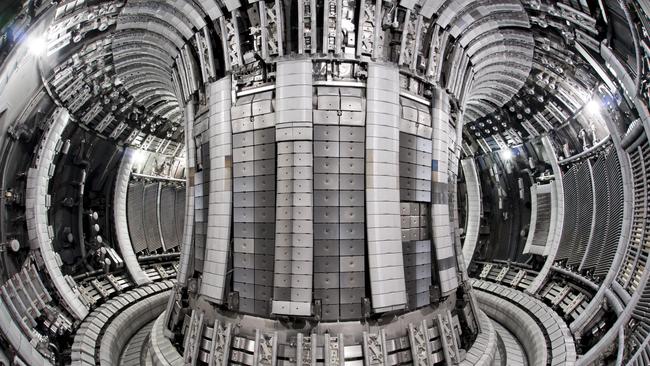

Here, over the course of those five seconds, a doughnut-shaped chamber managed to hold together a superheated plasma, 10 times hotter than the centre of the sun. Inside the plasma, hydrogen atoms fused to become helium nuclei, neutrons flew out and 59 megajoules of energy were made.

This output is less than a 250th of that produced by the coal and wood pellet-fired Drax power station in North Yorkshire, day in day out. It is far less than the energy put in to run the plant. It is also, though, more than double the record for fusion, set in 1997 by the same plant, the Joint European Torus (JET).

The result, fusion scientists said on Wednesday, cleared the path for the move to a commercial scale prototype, and – perhaps – the realisation of the long-held dream of clean and near-limitless energy.

Fusion power stations work on the same principle as the sun, producing energy by fusing two kinds of hydrogen atom – deuterium and tritium – under intense heat and pressure. The technical challenges to achieving this are immense. On Wednesday, Tony Donne, manager of the EUROfusion program, of which JET is a key part, said the latest results pointed a way to genuinely sustainable fusion.

“If we can maintain fusion for five seconds, we can do it for five minutes and then five hours as we scale up our operations in future machines. This is a big moment for every one of us and the entire fusion community,” he said.

Although the record was viewed as a milestone, more important was the way in which the power was generated. JET is a fusion test bed, to inform the design of a far larger fusion plant called Iter being built in the south of France.

When the 1997 record was set, the scientists found that tritium, one of the hydrogen isotopes used as fuel, was absorbed into the carbon walls of the reactor. That meant that more sustained fusion would not have been feasible. The walls were redesigned, using the metals beryllium and tungsten.

Wednesday’s results show that this wall does not absorb much of the tritium and can contain and sustain the fusion.

Tim Luce, head of science at the international nuclear fusion research and engineering experiment Iter, said that it gave them greater confidence in their project, an international collaboration that is expected to be operational from the mid-2020s and to begin fusion experiments in 2035.

“This is very important. The wall materials are the same, the operating scenarios are the same,” he said. “The know-how that’s been gained in this good result … will enable us to accomplish the Iter research plan.”

Among many scientists on Wednesday, the reaction was as much relief as joy. Because of the extent to which Iter relied on the findings from JET, which uses the same fuel mix, if the fusion had failed it would have suggested that the French reactor had significant problems to overcome.

Ian Chapman, chief executive of the UK Atomic Energy Authority, admitted that had the experiment not succeeded it would have put the multi-billion-euro project in jeopardy. “This was high stakes,” he said.

Ian Fells, emeritus professor of energy conversion at the University of Newcastle, said the achievement should be celebrated: “The production of 59 megajoules of heat energy from fusion over a period of five seconds is a landmark in fusion research. Now it is up to the engineers to translate this into carbon-free electricity and mitigate the problem of climate change.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout