Nord Stream: Attack on Putin’s pipeline remains a global mystery

Baltic ghost ships may hold answer to the destruction of Nord Stream as Ukraine war mystery takes an odd turn.

One evening last September the P524 Nymfen, a Danish naval vessel that tracks suspicious Russian shipping, made an unexpected detour from its usual patrol route.

For the first time in years, it skirted the Baltic island of Bornholm and made its way northeast to the outer fringe of Denmark’s estimated radar range. It paused for half an hour, turned around and switched off its transponder, vanishing for several hours from international tracking systems. Minutes later a Swedish air force surveillance aircraft began prowling back and forth nearby and a Swedish corvette set off for the site at speed before circling the waters.

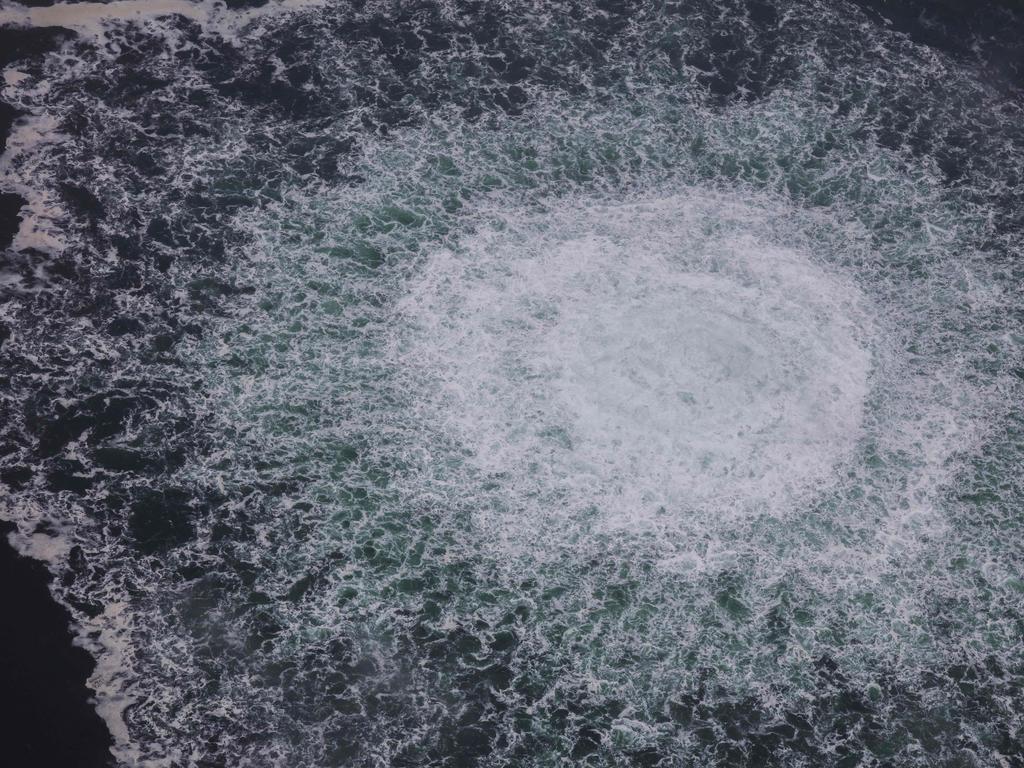

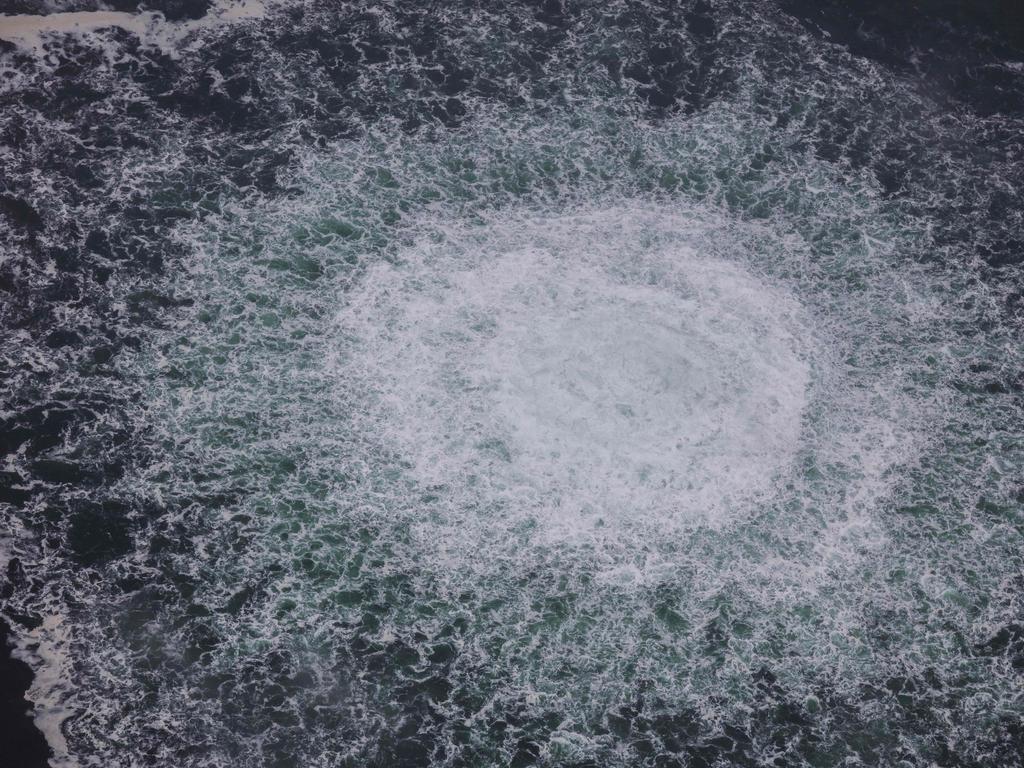

Four days after that the Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines, comprising a highly controversial project built to pump Russian natural gas directly to Germany, were knocked out by three underwater explosions in the same area, powered by the equivalent of about 500kg of TNT.

This audacious act of apparent sabotage is turning into one of the great geopolitical whodunits of the 21st century. Suspicion has been variously cast on the Ukrainians, the Russians, the Americans and even, fleetingly, the British and Poles. Fragments of clues have given rise to a profusion of theories, each seemingly stranger than the last.

The unusual Danish manoeuvres, first noted by independent Danish researcher Oliver Alexander and verified through navigation records, suggest there may be a few twists left in the story yet.

“It does appear that this Danish surveillance vessel went around the explosion sites for a reason,” said Jacob Kaarsbo, a former Danish intelligence officer who is now a senior analyst at Think Tank Europa in Copenhagen.

The bombings, which tore gaping holes in both strands of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline and one of Nord Stream 2’s, are a detective’s nightmare. For one thing, there were naval exercises by Poland, the Baltic states and Russia in the days before the incident, as well as NATO’s vast Baltops 22 war game two months earlier.

For another, there are at least three concurrent national investigations by Denmark, Sweden and Germany, patchily co-ordinated, while US Navy ships have also been spotted loitering nearby.

Out of this profusion of potential suspects and half-clues, four main theories have emerged: one probably wrong, one possible but perplexing, and two tantalisingly incomplete. The first is the shakiest. In early February, Seymour Hersh, the veteran US investigative journalist who exposed the My Lai massacre and the horrors of Abu Ghraib, published a long essay based on interviews with a single anonymous source. The bombs, Hersh claimed, had been planted by CIA divers with assistance from Norway. On closer inspection, however, much of the story disintegrated as researchers exposed numerous inaccuracies.

The second and most widely discussed theory emerged this month after a low-profile meeting in Washington between President Joe Biden and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz.

A vaguely worded report in The New York Times claimed there was intelligence pointing to a Russian or Ukrainian-speaking culprit, possibly a Russian opposition group or a network supporting Ukraine but acting without the knowledge or approval of its government. Hours later Die Zeit and two German public broadcasters released their own version of events, apparently founded on leaks from the German investigation.

It began with a Polish company chartering a yacht from the German port of Rostock. The six crew – a captain, a doctor, two divers and two diving assistants – were said to have travelled into the country on professionally forged passports, possibly in at least one case Bulgarian, to obscure their nationalities.

The yacht was subsequently identified as the Andromeda, a 15m Bavaria Cruiser 50 with several cabins and 75sqm of space below decks, available for $5000 a week. It set sail on September 6, first mooring at Wiek on the nearby island of Rugen, returning several days later by way of the tiny Danish island of Christianso. When German investigators finally searched the boat on January 18, they are said to have found traces of explosives on board.

While the Ukrainian government insists it had nothing to do with the bombing, the paper trail behind the company that rented the yacht is alleged ultimately to lead to a Ukrainian. The wealthy business magnate’s identity is an open secret among European diplomats and security officials.

Christianso, a speck of rock so minute that the surrounding archipelago is known as the “pea islands” in Danish, is 11 nautical miles northeast of Bornholm. Besides some handsome 17th-century fortifications once used to fend off the British and an impressively self-sufficient community of 90 with its own pub and one of the smallest schools in Denmark, the island’s chief attraction is its marina. Yachts can simply turn up, moor and pay for their berth electronically without booking ahead or notifying the authorities.

Danish police made their first inquiries about these payment records in mid-December, according to Soren Thiim Andersen, Christianso’s administrator. He said they had turned up in person on January 18, coincidentally the day the Germans began searching the yacht. With no surveillance technology in the marina, it is hard to identify individual yachts that have stayed there, particularly as there were up to 50 boats moored there in September. A Facebook appeal asking islanders if they had seen anything out of the ordinary seems to have yielded results, although the post has since been deleted and Andersen said he could not divulge any more information until Danish authorities were ready to go public.

It appears plausible the Andromeda was indeed in roughly the right place at the right time. However, Kaarsbo believes this a red herring, if not an ingenious attempt to throw investigators off the scent. There are, he notes, many puzzling questions. Is it really possible to lug half a tonne of TNT around on a pleasure yacht? Would it be a realistic base of operations for two divers to shepherd the explosives down 80m to the seabed in three manoeuvres, each of which must have taken hours?

“It’s really hard to see divers doing it without decompression tanks, which certainly couldn’t fit on a yacht,” Kaarsbo said. “Two guys swimming, say, 200m to 500m with hundreds of kilos of explosives at 70-plus metres depth isn’t possible. You can’t just drop it or steer it with two divers from a yacht to that depth with any kind of precision. Impossible. It would take highly specialised equipment that you couldn’t fit on a yacht.”

Other details seem odd if a Ukrainian was really behind the attack. Why go to the logistical trouble of doing it through Germany? Why do it in Denmark and Sweden’s maritime exclusive economic zones? Above all: why risk jeopardising German public and political support?

That leaves two more pieces of the puzzle. One is the Minerva Julie, a Greek-flagged tanker shipping out Russian oil through the Baltic. On September 2 it set off from Rotterdam. Four days later it rounded Bornholm and simply drifted around the two Nord Stream pipelines, occasionally firing up its engines when it came too close to Danish waters. Eventually it set a course for Estonia before docking in St Petersburg.

Its operator, Minerva Marine, has insisted it was waiting for its next instructions: “Drifting in a sea area awaiting voyage orders is standard shipping practice and there was nothing unusual in this instance.” Yet the Minerva Julie does not appear to have done so on any of its previous journeys in the months before the attack. The last clue lies in the movements of the P524 Nymfen, the Danish patrol vessel, and the Swedish warship.

Kaarsbo believes the likeliest explanation was a Russian submarine, or a ship that had switched off its electronic identifiers.

Besides the balance sheets of several German energy companies, the main casualty of the bombings is the sea. While scientific attention has chiefly focused on the 100,000 tonnes of methane that boiled to the surface, a more serious problem may lurk below. After a century and a half of industrial pollution the seabed off Bornholm is a toxic sludge of heavy metals, interspersed with 7000 tonnes of mustard gas shells dumped by the Soviet Union in 1947 on a site between the two Nord Stream pipelines.

Several weeks ago Hans Sanderson, an environmental scientist at Aarhus University in Denmark and a leading authority on this chemical weapons graveyard, published a preliminary analysis of the bombing. The modelling suggests the explosions churned up a quarter of a million tonnes of this sediment into two giant plumes, each almost 25km in diameter, containing 14 tonnes of lead and a smaller but deadlier quantity of TBT, an intensely noxious pesticide once used to keep the hulls of ships clean. “This is an important breeding area for cod … and this exposure was … at the end of their spawning season,” Sanderson said.

Marine biologist Marie Helene Miller Birk believes the impact could be even worse. The explosions coincided with the peak of the area’s twice-yearly algal bloom, a bonanza of the microorganisms that provide the foundation for an already ailing ecosystem. In other words, the toxins may have crept into the Baltic food chain from the bottom up.

Whoever carried out the sabotage, one thing is certain: the once monumental energy bridge between Russia and Europe is in ruins. It is not quite finished: Moscow is still quietly piping a little more gas into the European Union than is generally thought, with buyers ranging from Finland to Latvia and Hungary. Yet Russia’s total share of EU gas imports has collapsed from 40 per cent to 9 per cent. Bills went up across the continent but the much-prophesied winter shortages failed to materialise. Germany’s gas storage facilities are 64 per cent full, 22 percentage points higher than normal for this time of year.

“This was always a narrative that Gazprom (Russia’s state gas exporter) was pushing, that Europe cannot survive without Russian gas,” said Agnia Grigas, a Lithuanian-American energy analyst. “But the fact is we have seen this past winter there was no energy crisis. We’re talking about an energy realignment here.”

Heiko Borchert, a Swiss-based strategic affairs consultant, said the days of the Kremlin’s gas leverage over Germany were over, and Russia would become even more dependent on China as an ersatz market for its hydrocarbons. “I just can’t imagine the Germans saying (to Russia) a couple of years later: ‘Friends, the big fuss is over, we’re taking a sober look at the matter and the thing has to be brought back into business’. I struggle to imagine the German government would entertain that as an option.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout