Who blew up Nord Stream? Investigators focus on six mysterious passengers on a yacht

A yacht rented from a marina in Germany sailed near the Baltic Sea spot where the Nord Stream gas pipeline was blown up. The crew, some of whom were on fake passports, have disappeared.

The small marina on the edge of this north German city is a popular summertime spot for recreational sailors. German intelligence believes it was also the jumping-off point for the sabotage of the Nord Stream gas pipelines, an assault on Europe’s civilian energy infrastructure unprecedented since World War II.

On Sept. 6, a small group set out from Rostock aboard a rented yacht, the Andromeda, a slender 50-foot-long, single-masted sloop, ostensibly on a pleasure cruise around Baltic Sea ports. Within two weeks, the group returned the boat and disappeared.

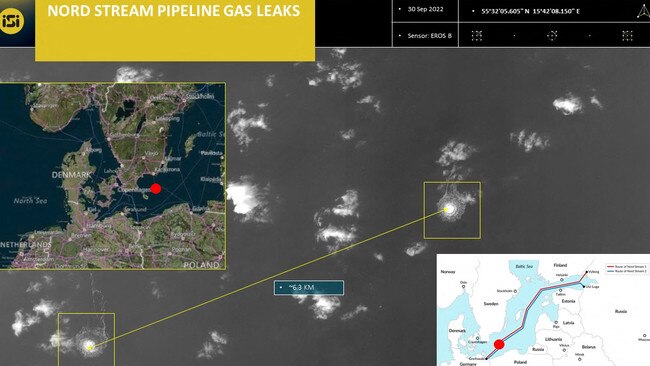

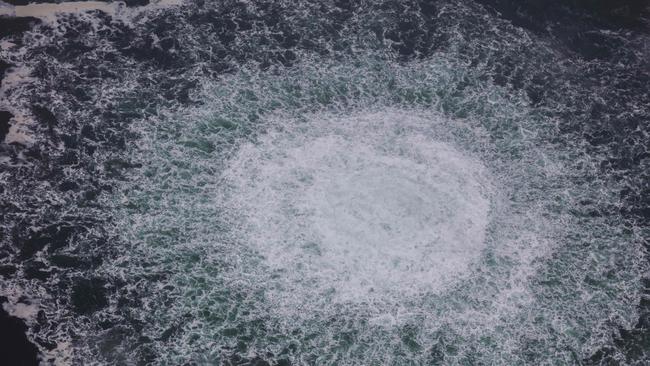

Not long after, on Sept. 26, a series of underwater explosions, powerful enough to register with seismologic measuring stations, tore apart three of the four main Nord Stream pipes, built to carry natural gas from Russia to Germany.

Hundreds of investigators from Germany, Sweden and Denmark, with the help of the US and other Western allies, mobilised to figure out who was behind the attack. Submarines surveyed the crime scene. Intelligence agencies scoured communications intercepts. Police sought witnesses.

Six months on, the mystery persists as investigators and analysts puzzle over who had the means, motive and opportunity to commit the crime.

Initial suspicions in many European capitals focused on Russia, which denied any involvement. Analysts speculated that only a state with a sophisticated military would have been able to carry out such a complicated, underwater attack.

Investigators now, however, are focused on the Andromeda and the six people it carried. German officials who have been briefed on the probe said they were told some of the people who rented the yacht were Ukrainian. Others had Bulgarian passports since determined to be forgeries, they said.

On Friday, German legislators who oversee the country’s intelligence agencies were briefed on the latest findings and admonished to keep them secret.

“The thesis that this must have been a state-sponsored action has seemingly collapsed,” said Ralf Stegner, one of the politicians. “It seems that we now know that it could have been a group of people who were not acting on behalf of a state.”

The focus on the boat crystallised in December. After combing through boat-rental records all along the Baltic Sea coast, investigators zeroed in on the Andromeda, according to officials familiar with the probe.

Last week, Germany’s general prosecutor said investigators in late January searched a boat they believed was connected to the blasts. Government officials said traces of explosives were found inside, leading them to believe the vessel could have carried at least some of the explosives used.

A representative of Mola Yachting GmbH, the yacht’s owner, said the boat searched was the Andromeda. The man declined to be named or to comment further. Prosecutors have said the company’s employees aren’t suspected of wrongdoing.

Investigators have established that the rental fee for the Andromeda was paid by a Polish-registered company, according to German officials. The officials said investigators believe the company is controlled by Ukrainian owners.

At least some of the six people on the suspected sabotage team boarded the Andromeda in Rostock’s Hohe Düne harbour, which caters to upscale tourists and hosts international yachting events. The Yachthafenresidenz Hohe Düne hotel there boasts luxurious rooms and bars with picture windows overlooking the waterfront.

From there, the Andromeda travelled to the Yachthafen Hafendorf in Wiek on the island of Rügen, a far more discreet harbour off the beaten track, with no camera surveillance at night, according to René Redmann, the harbour master.

Mr Redmann said his staff had checked in the boat and he had handed over the harbour logs to investigators. He said that his staff hadn’t registered the crew’s nationalities and that it wasn’t unusual for Eastern European tourists to pass through Wiek.

“We really have a lot of coming and going of charter guests with bigger ships,” he said, adding that he became suspicious about the visitors only when investigators reached out to him in January.

German investigators believe that it was in quiet, out-of-the-way Wiek that the suspected saboteurs loaded explosives — ferried to the port in a white van — and additional operatives onto the Andromeda, according to a German official briefed on the investigation.

After Wiek, the Andromeda sailed to the busier Danish port of Christiansø, farther north. The island is Denmark’s easternmost settlement, located an hour by boat from the larger island of Bornholm. Christiansø is home to a 17th-century fortress, one production facility — a tiny herring pickling company — and 98 residents, most of whom live along the pier, where throngs of boats dock every summer.

Søren Thiim Andersen, the administrator of Christiansø, said he received a request from Danish police in December asking for any records of boats that had entered the main harbour between Sept. 16 and Sept. 18, a little over a week before the pipelines blew up. The police returned in January to look at data from a machine on the harbour on which visitors register their boats, and to interview a few local residents.

At the request of the police, Mr Andersen said, he wrote a post on a Facebook page for the island’s residents, asking for photographs or video footage of the port from those three days. Three residents sent photos they had taken of the port area during those days.

The port master on the isolated island, John Anker Nielsen, said he was working on the days the Andromeda docked there, but he hadn’t noticed anything or anyone suspicious.

Among the questions facing investigators is whether six people and a boat the size of the Andromeda would be able to carry out such a major act of sabotage, which would have meant moving large amounts of explosives and diving gear and required the expertise of underwater demolition experts. And whether they might have been just one part of a broader operation.

Achim Schlöffel, a German extreme diver who runs a diving school and helps companies protect vessels and underwater installations from sabotage, said explosives could have been planted by a group of well-trained technical divers accustomed to working at such depths — around 80 meters — assuming they had several days to do so.

Six divers, he said, could have lowered the explosives in several dives using commercially available equipment such as underwater scooters or propulsion vehicles, airlifting bags and buoys, and a portable sonar.

“I know dozens of professional divers who would be up to the task,” Mr Schlöffel said.

Cmdr. Jens Wenzel Kristoffersen of the Danish navy disagreed, and dismissed the idea of a small team working from a sailboat as “a James Bond scenario.”

He said that while it’s possible for divers to reach the pipeline with good training, staying down for a prolonged period while manoeuvring explosives is more challenging. He said the operation would most likely have required a professional military unit skilled in underwater demolition.

The question of how the operation was conducted feeds directly into the bigger, and far more politically sensitive, question of who ordered it. A smaller operation using commercially available equipment would considerably expand the circle of potential culprits.

Authorities haven’t publicly disclosed any information about the identities of the six suspects aboard the Andromeda; their identities are the focus of the ongoing investigation.

Between June and July 2022, months before the Nord Stream attack, the Central Intelligence Agency sent a warning to its German counterpart, the BND, and other European services that a group might be preparing an attack on the pipeline, according to intelligence officials familiar with the notification. The warning included information about three Ukrainian nationals who were trying to rent ships in countries bordering the Baltic Sea, including Sweden, these officials said.

In October, shortly after the blasts, senior US security officials visiting Berlin mentioned the possibility that Ukraine might have been behind the attack, according to a German official who spoke with them at the time. US officials now say private Ukrainian actors could have organised and financed the bombings without the knowledge of the Ukrainian government.

Ukraine officials, including President Volodomyr Zelensky, have denied any involvement in the Nord Stream sabotage, saying the accusation played into Russia’s hands.

Any direct involvement by Kyiv would be damaging for the unity of the Western alliance that is backing Ukraine’s war effort. Such a revelation would have a particularly negative impact on the government of German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, who discarded his nation’s pacifist stance to become the world’s third-largest supplier of weapons to Ukraine and one of its biggest financial backers, despite misgivings among German voters.

Germany’s defence minister, Boris Pistorius, warned last week that there is no clarity as to who was behind the attack, and that there is a possibility of a false-flag operation designed to blame Ukraine even if it had no involvement in the sabotage.

On Tuesday, Russian President Vladimir Putin dismissed any suggestion that Ukraine, or any pro-Ukrainian group, could have blown up the pipelines, and blamed the US, which has denied involvement.

He also said a Russian investigation found that there could be unexploded devices that remain attached to the pipelines.

“Apparently, several explosive devices were planted; some exploded, but some didn’t. It’s not clear why,” Mr Putin told state television.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout